Stephen King, 69, has sold more than 350 million books, and tries not to apologise for being working-class, or imaginative, or rich. The snobbery has ebbed a little, though; in 2003 he won the National Book Foundation’s Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters, and now the BFI is screening a series of adaptations of his novels, which show how versatile he is. Why can’t you write stories like Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption, a woman asked him once. I did write it, he told her, but she did not believe him.

King has published 59 novels, but he is a recovering addict and can’t remember writing them all. Most of Cujo (1981), a story about a rabid dog and adultery, is news to him. Tabitha, his wife of 46 years, would sometimes find him asleep on a keyboard dotted with vomit, or blood, with cotton swabs stuck up his nose. ‘All that’s dangerous and sick and foul within me I’m able to spew into my work,’ he says. Or, as his grandfather said, ‘When Stephen opens his mouth all his guts fall out.’ As an adult, King treated that observation as a bet.

He says he fears insanity and that when he writes his nightmares stop. In his memoir On Writing (1999) he wonders if he might have become a mass murderer without fiction. I find this hard to believe but perhaps I am thinking of an older, slightly happier King, living calmly in a parody ‘monster mansion’ in Maine, New England. He didn’t even leave his wife when he became a multi-millionaire. I don’t think he would eat any heart but his own.

His father was a travelling salesman, who disappeared when Stephen was two: he went out to buy cigarettes and never returned. He was raised poor, by his mother, the first person to pay him for writing. ‘As a kid,’ he says, ‘I went to see every horror movie I could possibly see. Sometimes my brother went with me. My brother’s two years older, and he would put his hat over his face. I never put my hat over my face.’

He married Tabitha and became a schoolteacher, like William Golding and Evelyn Waugh. As they raised three children on a pittance he wrote stories for magazines called Dude, Cavalier, Startling Mystery Stories and Swank. Carrie (1974), a novel about adolescence and telekinesis, was his breakthrough and his first successful splice of two good ideas to make a great one. Tabitha picked it out of the wastepaper bin and Brian De Palma made it into a terrifying film. King’s plots have always attracted great directors because he’s an ideal man to butcher. He writes like a journalist — a hack still, but what a hack — and a man being devoured. In ‘Survivor Type’ (1982), a surgeon amputates and eats his own body parts; he only ceases to record this, for us, when he has eaten his fingers. In Salem’s Lot (1975) Jimmy Cody is devoured by rats. When he opens his mouth to scream, a rat eats his tongue. Or it did. King’s editor made him cut it, to save the publisher’s screams.

King was superficially pliant. He took the cut. Cody was impaled instead, but King had his revenge. In The Plant (2000), he sends a possessed plant to a publisher. The novel is unfinished, but I am sure it will eat the publisher eventually. In Misery (1987), he murders his Number One Fan with a typewriter because she has abducted him, cut off his foot and, worse, tries to make him write genre fiction. He later said that Annie was really cocaine; even so, how does King manage to have so much fun in hell? Many of his protagonists are writers: in Salem’s Lot, in ‘1408’ (1999), in The Dark Half (1993), in the magnificent The Shining (1977), as fine a novel about alcoholism as The Strange Tale of Dr Jeckyll and Mr Hyde. In The Body (1982), a tale of childhood friendship and abuse that became the Rob Reiner film Stand By Me, Chris tells Gordie: ‘You’re going to be a great writer some day.’ King was writing about King, and he was right.

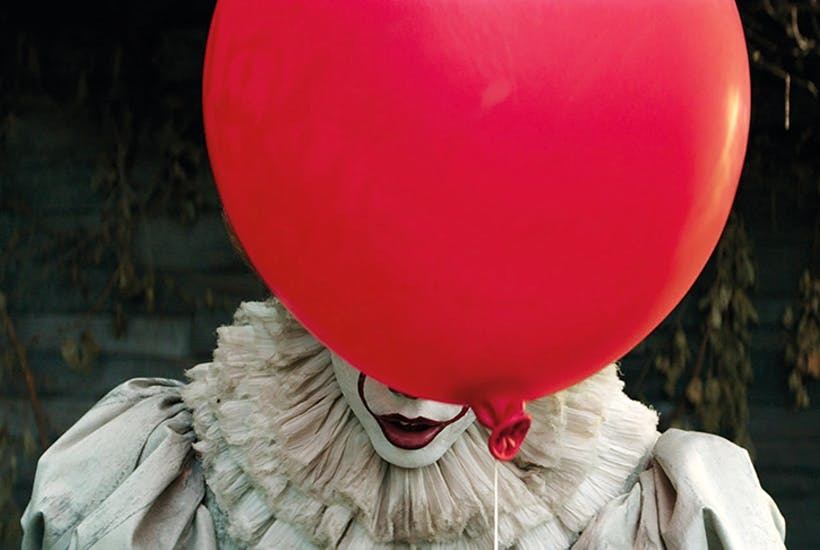

King can make everything horrifying, and still I can laugh. In It (1986), an entire town (in his native Maine, of course) is possessed by a monster who often appears as a clown. This must be said in any serious study of King: clowns hate him. They blame him for the ‘creepy clown’ epidemic, which has led to multiple clown arrests. The president of the World Clown Association said: ‘It all started with the original It. That introduced the concept of this character. It’s a science-fiction character. It’s not a clown and has nothing to do with pro clowning.’

The supernatural element is not the dread part of his fiction; this is what makes it palatable because King, essentially, writes fairy tales. The real horror is domestic, as it is in life, always. In The Mist (1980), the horror is not that monsters invade a town. It is that a man kills his son to protect him, and then the monsters leave, so the child dies pointlessly. In It, the horror is that the adults are immune to the deaths of their children.

Sometimes he forgets to write ghosts, or vampires, or aliens at all. Dolores Claiborne (1992) is about a woman seeking to protect her daughter from her father’s lust. In the film, the scene in which Dolores realises that her husband has withdrawn her savings — gathered carefully by drudgery over many years — stays with me. King writes women very well. He likes them. He was brought up by his mother.

This is, partially, why he hated Stanley Kubrick’s famous film of The Shining. The novel is about a writer going mad; in Kubrick’s film, he is already mad. ‘And as far as I was concerned, when I saw the movie, Jack [Nicholson] was crazy from the first scene,’ he says. ‘I had to keep my mouth shut at the time… And it’s so misogynistic. I mean, Wendy Torrance is just presented as this sort of screaming dishrag.’

With his anger and fear safely channelled into his fiction, King appears a gentleman, notoriously kind to younger writers. ‘He’s not competitive,’ his agent Chuck Verrill once said. ‘The only guy he ever cared about was Tom Clancy. They were both at Penguin once, and it was made clear to King that he was seen as the second banana to Clancy. He didn’t like that.’