On 3 September 1968, Allen Ginsberg appeared on William F. Buckley’s Firing Line. Buckley exposed Ginsberg’s politics as fatuous — the blarney, stoned — but Ginsberg stole the aesthetic victory by reading ‘Wales Visitation’, a homage to William Blake. ‘White fog lifting and falling on mountain brow,’ Ginsberg intones, ‘…teeming ferns/ exquisitely swayed/ along a green crag/ glimpsed through mullioned glass in valley rain.’

‘Nice,’ Buckley nods. He lets Ginsberg read the whole poem. Ginsberg opposes the artificial imagery of power and money (‘London’s symmetrical thorned tower / & network of TV pictures flashing bearded your Self’) to the vision of the unmediated, natural Self: ‘Each flower Buddha-eye.’ After six minutes, the roots of Christianity mesh with oriental religion in a vision of physical liberation and spiritual democracy: ‘Sounds of Aleph and Aum / through forest of gristle… All Albion one.’

‘I kinda like that,’ Buckley admits. Even secondhand and soiled, the visionary voice cannot be denied. Buckley believed that ‘the ideologues, having won over the intellectual class’, had now ‘simply walked in and started to run things’. Blake had stood athwart history, yelling ‘Stop’ to the rationalising, systematising civilisation that coalesced in Georgian London, then conquered the world after 1945. The further the market spread, the higher Blake’s stock rose. In 1863, Blake’s first biographer Alexander Gilchrist called his subject pictor ignotus, the unknown painter. A century later, Blake was a universal poet, the prophet of spiritual revolt in what Buckley called ‘an age of conformity’.

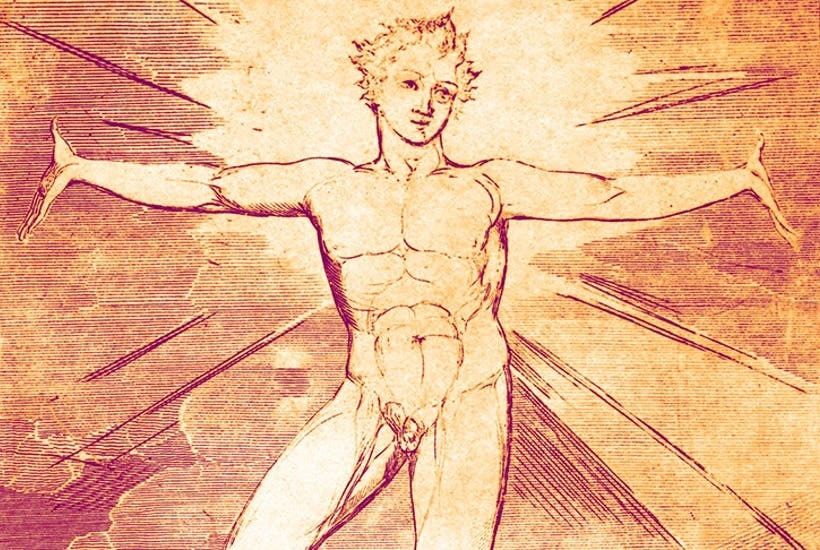

Blake’s belatedness encourages us to judge him not by his works, but his admirers. A century before Firing Line, Swinburne, anticipating Allen Ginsberg in Blake: A Critical Essay (1868), spotted ‘the points of contact and sides of likeness between William Blake and Walt Whitman’. But Blake, working with ‘Ages & Generations’ in mind, had hoped for the Blake revival. Before Joni Mitchell called her spoilt and selfish peers ‘stardust’, Blake wrote that ‘Energy is the only life’, and got back to the garden, naked in Lambeth, not Woodstock.

He even named the age when, as in the era of the French Revolution, ‘Fury! rage! madness! In a wind swept through America.’ ‘Rouze up O Young Men of the New Age! Set your foreheads against the ignorant hirelings!’ Blake wrote in the preface to his epic poem ‘Milton’ (1810). ‘Suffer not the fashionable Fools to depress your powers by the prizes they pretend to give for contemptible works or the expensive advertising boasts they make of such works.’

Accompanying an exhibition at Northwestern University in Illinois, William Blake and the Age of Aquarius is the most intriguing book on Blake since Marsha Keith Schuchard’s exposé of him as a swinger, Why Mrs Blake Cried (2006). America’s postwar Blakeans rebelled against expensive advertising and contemptible comfort. However misplaced the fury, and despite a preponderance of ‘fashionable Fools’, the results were not all contemptible. The political inspirations are well known; Blake, in Ginsberg’s words, warned Thomas Paine to ‘get out of London before the fuzz came to arrest him’. But many other Blakean echoes are surprising.

I knew that Blake supplied the chorus lyric to the Doors’s ‘End of the Night’. But I didn’t know that Jimi Hendrix, while living around the corner from the blue plaque marking Blake’s residence in South Molton Street, drew on Blake’s ‘Mary’ for ‘The Wind Cries Mary’, and on ‘Jerusalem’ for the ‘arrows made of desire’ in ‘Voodoo Chile’. Nor did I know that Kris Kristofferson discovered Blake at Merton College, Oxford, where he played rugby and won a boxing Blue.

Another highlight is Jacob Henry Leveton’s essay on Blake’s Abstract Expressionist connections. Blake’s innovations in colour printing influenced Sam Francis’s adoption of ‘vibrant color kineticism’. Clyfford Still quoted Blake’s individualist Christianity against the impersonality and fear of the Cold War. In Fearful Symmetry (1947), Northrop Frye described the vortex as Blake’s ‘image of infinity’; in the same year, Jackson Pollock painted ‘Vortex’.

‘One law for the Ox & Lion is oppression,’ Blake wrote in his age of conformity. Perhaps it is only a matter of time before Blake’s defence of religious conscience and free speech leads modern conservatives to concur with Kris Kristofferson: ‘William Blake is my man… Hell, yeah!’