‘It was Plato who said storytellers rule the world,’ observes Mariana Mazzucato, her powerful voice tempered with a beaming smile, ‘But the stories we’re constantly told about how value is created are largely myths. We must rethink where wealth really comes from.’

An economics professor at University College London, Mazzucato is fast emerging as one of the world’s leading public intellectuals. From her high-ceilinged office in Bloomsbury, a host of grant-making bodies on speed dial, this 49-year-old Italian-American is determined to ‘replace our current parasitic system with a more sustainable, symbiotic type of capitalism’.

Mazzucato emerged from the academic shadows five years ago, when she wrote The Entrepreneurial State. The book was a cogent reminder, at a time when the public sector is much maligned, that government has played a powerful innovative role in the modern economy, creating much of the technology behind the world’s most successful companies.

‘Take Apple’s smartphone,’ says Mazzucato, picking up my device from her desk. ‘Everything that makes this “smart”, from the internet to GPS technology to the touchscreen, was, at the outset, due to publicly funded research. Likewise, the science that produced Google’s search algorithm, the key to its success, was also publicly funded.’

She sees the state as the unacknowledged enabler not only of the consumer electronics revolution, but of advances in sectors from pharmaceuticals to energy extraction. ‘Public bodies in the US, UK and elsewhere have financed game-changing research into everything from new drugs to fracking,’ she argues. ‘The state, far from being a hindrance to value creation, or an obstacle, has actually been the investor of first resort — and these narratives matter.’

In The Value of Everything, published last week, Mazzucato sharpens her focus, not only lauding the role of ‘mission-oriented’ public investment, but honing her critique of the private sector too. The state ‘should do far more to strike deals with private sector players benefiting from publicly funded research,’ she says. ‘The US government, for instance, should have negotiated a share of the upside from helping to invent Google’s algorithm — which could have financed an innovation fund to create the next round of Googles.’ Instead, we have ‘a travesty of justice’ as ‘the tech companies that have benefited enormously from public investment go to extravagant lengths to avoid paying tax’.

More broadly, ‘many of the businesses we are told are value creators are actually value extractors,’ says Mazzucato. ‘With companies driven solely to maximise shareholder value, we misidentify taking with making, losing sight of what value really means.’ The Value of Everything, says Mazzucato, is a response to the 2015 election, when David Cameron prevailed over Labour’s Ed Miliband. ‘I was shocked that there were a number of Labour party figures, including Tony Blair, who said we had lost because we didn’t embrace the wealth creators,’ she recalls. ‘I thought: no, we lost because centre-left politics has lost its dynamism and control of the narratives about where wealth comes from.’

Since then, via the lecture circuit and TV studios and discussions with numerous politicians, Mazzucato has been spreading her message with gusto. A passionate remainer, she resigned her position advising shadow chancellor John McDonnell because Labour was ‘too pro-Brexit — but that’s another story’. Since then, she has been advising First Minister Nicola Sturgeon on plans to set up a Scottish National Investment Bank and also working closely with [Business Secretary] Greg Clark.

As articulate as she is, some of Mazzucato’s statements are, frankly, quite scary. With public spending in the UK already around 42 per cent of GDP, how high does she think it should be? ‘Anywhere from 50 per cent to 100 per cent is fine.’ Is it really ‘progressive’, I ask, for the government to be spending more than £50 billion a year on debt service, more than on schools, while storing up liabilities for future generations? ‘The attention on the deficit is misplaced,’ she says. ‘Because we’re not making the investments required, both in the public and private sector, productivity has been very low — which lowers GDP growth and generates high debt-to-GDP ratios.’

And what if companies don’t agree to ‘share the upside’ with governments? ‘Capital gains is way too low and it’s crazy we don’t have a financial transactions tax,’ she shoots back. ‘We could also go back to an old-fashioned tax system — the top rate of tax used to be 90 per cent, that’s always an option.’ Sensing my unease, Mazzucato counters. ‘Look, I’m not naïve about the state — I’m an Italian after all,’ she says, hitting me again with that effervescent smile. ‘But if we don’t want such tax levels, we need to get creative about using state investments to drive innovation, while capturing some of the upside for the public purse.’

Mazzucato’s ideas, easy to dismiss perhaps, are attracting ever wider attention. That’s good, as much of her analysis rings true. It is simplistic to say, as many do, that markets are always good and governments are always bad. It is right to call out big companies, as she does superbly well, for channelling ‘ever more of their profits into share buybacks, which boost equity prices and executive bonuses, at the expense of investment in both skills and capital equipment’.

Mazzucato has offered the left a positive vision of growth based on innovation and profit-sharing, rather than sterile and counter-productive analysis based on the politics of resentment and expropriation.

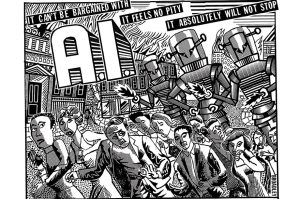

And with the once-eulogised tech giants now facing a reputational crisis, Mazzucato’s ideas could soon get more popular still. ‘We have had value-extraction throughout history,’ she says. ‘The difference now is that modern capitalism uses a discourse relating to dynamism and innovation, painting the state as the problem, while the Silicon Valley guys position themselves as do-gooders.’

Supporters of small-state capitalism need to make it work better, for a broader range of people — and fast. Big-state capitalism has a media-savvy new champion, and she’s only just getting started.