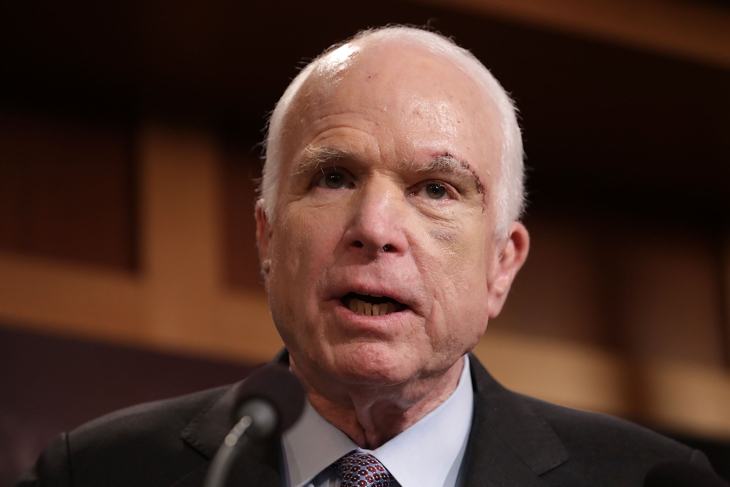

John McCain is dying, and with him is dying a Republican Party that was never born. The Arizona senator has to be understood in relation to the GOP because he has never really been the “maverick” that pundits made him out to be after his first White House bid eighteen years ago. Before then, he was seen as a reliably conservative Republican, albeit a more hawkishly internationalist one than was the norm for the GOP in the Bill Clinton era. Those were the days when Republicans like George W. Bush swore on an oilman’s bible that they were against “nation building.” McCain was more honest about his interventionism, which made him the neoconservatives’ first choice in 2000.

Writing in The Weekly Standard that year, Bill Kristol and David Brooks described McCain as “at once heterodox in tone and conventional on most issues.” So he was, and so he has remained. The “maverick” is a myth. Even in the Trump era, McCain’s deviations from his party have been rare, his decisive vote against Obamacare repeal last year being a notable exception. Tone can be everything, though. In his twilight, McCain still says things that enrage stalwart Republicans and win applause from establishment liberals. He doesn’t want President Trump at his funeral, the New York Times reports. He wishes he’d chosen Joseph Lieberman—another dubious maverick beloved by insiders—instead of Sarah Palin as his running mate in 2008.

In his own home state of Arizona, the Republican Party has already changed in ways that make McCain seem like a living fossil. His Senate seat was held by Barry Goldwater before him. His fellow senator from Arizona, Jeff Flake, was once executive director of the Goldwater Institute and seemed like he would carry on the libertarian-lite tradition of the Republican west. Instead, Flake has decided not to run for re-election because, in the age of Trump, he could not even secure the Arizona GOP’s nomination. Goldwater and McCain were at times uncomfortable with social conservatives, who became the base of the GOP nationwide in the 1990s. (They were often uncomfortable with one another, too: McCain was not necessarily a “Goldwater Republican” in Goldwater’s eyes.) Now social conservatives have been bolstered by nationalists and populists who despise McCain for his compromising views on immigration and addiction to foreign adventurism.

The Republican Party that McCain aspired to create and lead in 2000 would have been a more socially libertarian and perhaps even more interventionist version of the party that George W. Bush led. But Bush destroyed that party through his blunders, and by the time McCain was picked to succeed him, the GOP and the country had moved on. Ron Paul, not McCain, was the standard-bearer for libertarian Republicanism by then, as his son Rand Paul is today. Bill Kristol, sensing that McCain needed a running mate with credibility among the grassroots right, lobbied to put Palin on the ticket. Instead of Palin’s populist credentials saving McCain Republicanism, however, her popularity with the base confirmed that the future would belong to someone like Donald Trump. George W. Bush’s wars and mismanagement of the economy achieved what Pat Buchanan’s campaigns in the 1990s had not been able to do—to turn the GOP toward nationalism.

If McCain had been in the nominee in 2000 instead of Bush, would the same thing have happened? McCain was the better man than Bush, with the scars to prove that war was no mere exercise in idealism to him. But that doesn’t mean he would have been a better president. The remarkable thing, looking back at what Kristol and Brooks wrote about McCain at the turn of the century, is how they wanted McCain to play exactly the role that Trump now plays, albeit with a different policy script. “The McCain insurgency is not ideological. It does feature certain themes and principles, but they are not yet fully developed into a governing agenda,” they wrote. “McCain is trying to bring new and unlikely blood into Republican ranks. … Many of these new Republican primary voters seem ill-suited to the GOP. But that’s what insurgencies do. They expand the base. They topple the old establishment by bringing in new people. They create new alliances within the party.” Imagine Kristol affirming that in the Trump era!

“John McCain could cruise to such a massive win in New Hampshire because the Republican establishment has ossified,” they went on. “He attracted independent voters by stressing a reform agenda not part of conservative orthodoxy. But he also beat Bush among voters who called themselves conservative. The conservative establishment turned out to be almost as out of touch with real conservatives as the GOP establishment was with the Republican rank and file.” Kristol and Brooks recognized an opportunity to remake the Republican Party 20 years ago. Only the man to take that opportunity would not be John McCain, but Donald Trump.