Once won, rights and freedoms are taken for granted. We all find it difficult to imagine life before the Married Women’s Property Act, when everything belonging to a wife — goods, chattels, children — automatically became the sole property of her husband. Those born since the 1960s can’t really envisage what it was like for practising homosexuals in those days. By a similar token, the mind can scarcely take in the fact that in Penal times, Catholics could not buy or sell land; or that it was an imprisonable offence for Catholics to run a school. It was a legal offence to dress as a monk or a nun out of doors.

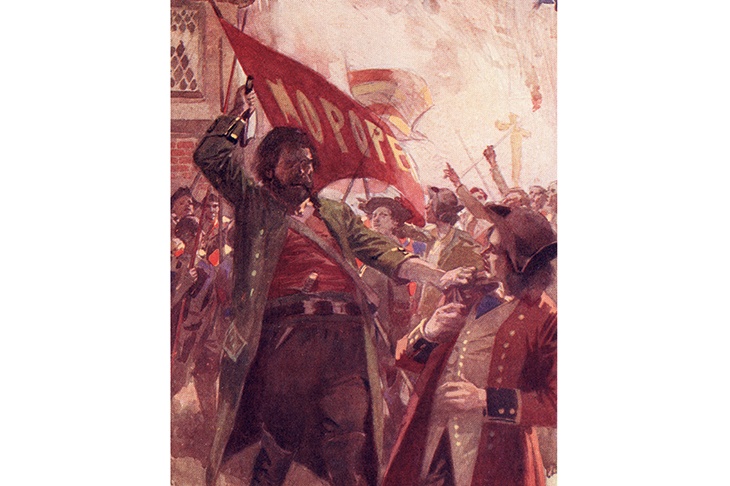

It was the relaxation of these stringent and, by then, totally unnecessary, laws, which led, in the hot summer of 1780 to the so-called Gordon Riots, in which Lord George Gordon inflamed the worst mob violence London had ever seen, with more than 1,000 dead. The rioters were not conspicuous for their theological subtlety. When called upon to attack a house because ‘there are Catholics there’, one group shouted back: ‘What are Catholics to us? We are against Popery.’

It is with these terrifying scenes, familiar to readers of Barnaby Rudge, that Antonia Fraser begins her unflagging narrative. Her book traces that half century between the Gordon Riots and the moment, in 1829, when the Tories, guided by the Duke of Wellington, realised that enough was enough, and the anti-Catholic laws could safely be repealed. Indeed, that in Ireland, it would not be safe until they were repealed. The Duke of Norfolk, and the few remaining Catholic peers, could fish out their ancient robes of state and take their seats in the House of Lords. Catholic schools could function legally, and the religious orders, many of whom had fled from revolutionary Europe, could lead their prayerful lives without the authorities worrying that a new Gunpowder Plot was being hatched.

Fraser brings out the centrality of Ireland to the story. Had it not been for the possibility of Ireland exploding like a tinderbox, the anti-Catholic laws might have lain mouldering on the shelf at least until the stubborn old Hanoverian uncles had given place to their young niece, Victoria.

Above all, it was Daniel O’Connell, the burly Lincoln’s Inn barrister, who was elected to Parliament in the Co. Clare by-election of 1828, who forced the eventual change in the law. O’Connell, one of the most eloquent orators of his day, had been campaigning for years for the rights of Catholics, of whom he was one. ‘My title to sit [in the Commons] is clear and plain.’ But he refused to take the oath which, among other things, declared that ‘the sacrifice of the Mass and the invocation of the Blessed Virgin Mary and other saints, as now practised by the Church of Rome, are impious and idolatrous’.

As Fraser’s title suggests, the sticking point was not only the religious oath required by parliamentarians. Fundamental to the delay in passing any form of relaxation of anti-Catholic laws was the stubbornness of successive monarchs. George III and George IV both felt bound by their coronation oaths which had been specifically Protestant. I was amazed to read that the wording of the coronation oath remained unchanged until the coronation of George V; and that Edward VII, much to his embarrassment, felt forced to repudiate transubstantiation and the invocation of saints before he could be crowned.

This is an absolutely splendid book. With the brio and narrative skill which has been in evidence since her first book — the irreplaceable classic biography of Mary Queen of Scots — Fraser gives us a vivid account of Catholic Emancipation. Some of the most dramatic scenes in our parliamentary history are here brought to life with unmatched verve.

But this is a history whose remit and implications are much wider than the narrow one of how a religious minority achieved their rights in 1829. The story anticipates the libertarian political thinkers of the future, above all John Stuart Mill and John Rawls. As the tale of Catholic Emancipation unfolds we feel the politicians slowly learning the lessons of what might one day make a just society, in which minorities are given the same rights under law as the majority.

Skilled storyteller that she is, Antonia Fraser has woven into her narrative the unavoidable questions which face our own society, vis-à-vis minorities. The secular consensus which today dominates public discourse in Britain and Northern Europe does not need to bring back laws to discriminate against Catholics (or, for that matter, against any practising Jew, Christian or Muslim). Secularism, however, has created a climate of intolerance which will make some of these pages uneasy reading for those who would like to think that we have evolved into a more liberal society.