Yes

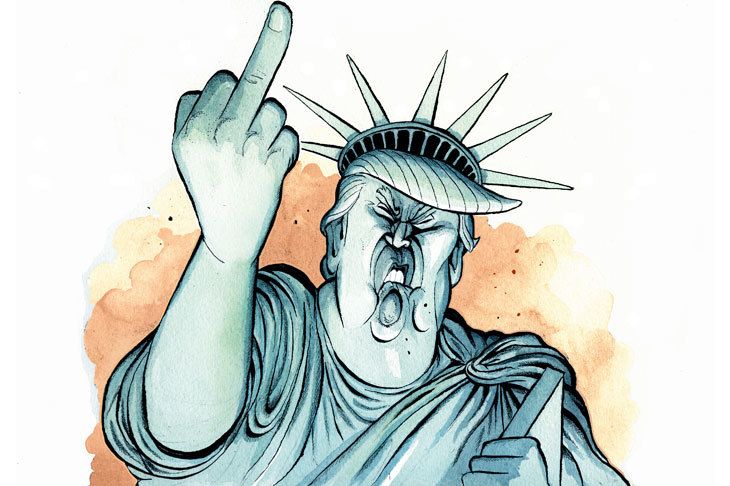

Supporters of the global free-trade regime that has been built up over the past 25 years like to think of themselves as capitalists. Benevolent capitalists, perhaps — ones who have only the interests of the world’s poorest workers and their own nations’ least wealthy consumers at heart — but capitalists nonetheless. So why is the biggest beneficiary of their world order in fact the last of the great, deadly serious Communist states — the People’s Republic of China?

Trump’s tariffs, far from being the end of the liberal economic order, may be the one thing that can save it. That order, after all, to an embarrassing degree depends upon America’s dominant position in the world. After the second world war, America helped to rebuild the industrial economies of friends and former foes alike. Even as American goods flooded Europe — or at least those corners of the Continent that could afford them — Washington dedicated extraordinary quantities of taxpayers’ dollars to other countries’ needs. The Marshall Plan was only a fraction of the real cost, which included above all the military support that America supplied. Building a welfare state is much easier when someone else is picking up your national defence tab. American motives were not entirely altruistic, but it was a good deal for Europe, and East Asian allies too.

By the 1980s, though, the system started to crack. American industry had been so far ahead for so long, and had grown so large and so lazy, that it began to lose its competitive edge. Japan and Germany, the old foes who were the greatest beneficiaries of the American order, continued to rely on Washington’s defence largesse even as they began to compete as peers — or more than peers — with American industry. Washington itself, meanwhile, seeing the benighted state of many domestic manufacturers, decided that a dose of international competition was the cure. China took note. So did American firms that decided they could maximise their shareholder revenue and their executives’ compensation by dismantling their own production chains: they could lay off an expensive American workforce and hire a cheaper one in Mexico or Asia; and they could outsource the components of their products — cell phones, computers, cars, even fighter jets — to specialist manufacturers in countries whose governments and business elites jointly put a priority on the most high-value and technical kinds of manufacturing. While the American business elite fascinated itself with chatter about brands and intellectual property and making products cheaper all the time, savvier countries focused on being able to do the making best. Meanwhile, US taxpayers continued to be on the hook for Cold War allies’ defence, even though the world economic conditions and domestic industrial advantages that had allowed America to be so generous had long since evaporated.

No one can blame Europe or Japan for taking advantage of a system that lets them have it both ways for as long as it lasts: a system that lets them shift the burden of defence — any state’s first imperative — on to a friendly hegemon, even while working assiduously to tear apart the hegemon’s industry.

The present broken world economic system will continue to empower China relative to the US for as long as China lets it run. President Xi Jinping would be happy to see it run forever — or at least until it reveals that America is no longer strong enough to be plausible as even a nostalgic hegemon. At that point, China will have won a world war without firing a shot.

The tariffs shock American elites because they show that Trump does not believe in the myth of infinite American power — so vast that the moment of supremacy after the second world war need never end — and they endanger the elite’s scam of getting rich off chopping up and selling American industry. European leaders are shocked that their free ride might come to an end: they cannot continue to receive a subsidy from Washington — in the form of defence — while they chip away at the American economy that makes the subsidy possible. And China is shocked that the self-liquidating superpower of the West might not be so self-liquidating after all.

Trump’s instincts are correct. No major country on earth can successfully retaliate against America in a trade war, for the simple reason that America has trade deficits with them all. America has proven more than once that its large and rich internal market can support itself, and if consumer prices rise, there is a point up to which a marginally more expensive flat-screen TV is worth the higher price in exchange for more Americans making those TVs in the first place. The calculation isn’t simply an economic one, but a strategic one too. Steel is a place to start because it shows in clear terms how the entire global economic scam works. China subsidises its industry and produces so much steel that the world price falls. This is uneconomical, but strategically smart. Allies of the US lower prices accordingly — sometimes they have their own elaborate forms of indirect protection, and sometimes they simply re-import Chinese steel — and the US steel industry, once the world’s leader, shrinks. American industries that depend on steel then come to depend more on imports, and ultimately on the Chinese subsidy for the global market. When American steel production has been weakened enough — it’s not an industry that can be rebuilt in a day — China can cut its subsidies, watch prices rise, and gain tremendous leverage over everyone who needs steel, including the steel-using industries of what was once the world’s sole superpower, the United States: no longer a nation of power producers, but one of dependent consumers.

Daniel McCarthy is the editor of Modern Age.

No

On the whole, Donald Trump’s bark has been worse than his bite. The sour and silly rhetoric has not always translated into damaging policies, let alone the fascism his critics warned us to expect. His trade policy may prove to be an exception. In retracing the steps of his disastrous predecessor Herbert Hoover, who signed the Smoot-Hawley tariff act of 1930 that triggered a trade war and great depression, he is juggling gelignite.

Theresa May, coming from a country with a long record of championing free trade, should channel her inner Gladstone at the G7 summit in Canada and give him a sharp economics lesson. She should begin by explaining that he is putting America last.

Imposing tariffs, said the famous economist Joan Robinson, is like blockading your own harbours, rather than those of your enemy, during a war. The President’s 25 per cent tariffs on steel and 10 per cent on aluminium from Mexico, Canada and the European Union will punish American consumers far more than they will hurt foreign producers or help American producers. We know this from countless historical examples of trade protectionism and its opposite — unilateral moves towards free trade. We don’t need, surely, to rehash the logic explained by Adam Smith, David Ricardo and Richard Cobden.

Countries that cut or abolished tariffs without waiting for reciprocation, such as Britain in the 1840s and 1860s, or Hong Kong, Singapore and New Zealand more recently, have thrived. Countries that imposed tariffs, such as America in the 1930s, have generally impoverished themselves. Worse, the spiral of retaliation that followed Smoot-Hawley helped those in Japan who argued that conquest was a better way of getting resources than trade, and thus ended in Pearl Harbour.

Retaliation to the Trump tariffs has already begun. Mexico is promising tariffs on American lamps, pork, cheese and flat steel; Europe on motorcycles, denim, cigarettes, peanut butter, whisky, orange juice and cranberry juice. These are carefully calculated to hit the home states of the House speaker (Paul Ryan’s Wisconsin) and Senate majority leader (Mitch McConnell’s Kentucky). The EU needs little encouragement to indulge in protectionism. Mr Trump’s protectionism is designed to help him in November’s mid-term elections; it may backfire.

But the impact of retaliation on American producers is in some ways the least of the problem. Consumers will suffer most from the tariffs, and everybody is a consumer, including, of course, those who work in the steel industry. Deliberately raising the price to the American economy of steel, a crucial ingredient in everything from cars to cables, is self-harm.

It certainly does not help with ‘national security’, not least since most steel comes from allies like Canada (very little American steel comes from China, by the way). Indeed, by raising the cost of ships and planes, the tariffs on steel and aluminium will make America slightly less able to afford its own defence.

Even — especially — if the Canadians were deliberately dumping steel on the American market below the cost of production, rather than just being competitively cheap, the American consumer would be the beneficiary of the dumping, the Canadian producer the sufferer. Does a supermarket hurt you when it discounts a product? The distant threat that later, having destroyed all its international rivals’ steel industries, Canada will corner the steel market and raise prices, is absurd.

China did try pushing up prices of rare-earth metals a few years ago, having achieved something approaching a monopoly in their mining. It was a failure; how much harder would it be to corner the market in steel?

Remember, trade is not some government arrangement. It is a matter of millions of individual, voluntary transactions entered into because people benefit from them. Mr Trump is punishing American consumers for the decisions they take. If Americans choose to swap cheaply printed pictures of dead American presidents for useful steel from Canada, who is to say they are wrong? The Canadians will often use those bits of paper to buy American goods, services, property or bonds, to the benefit of Americans. Win-win.

By contrast, Mr Trump’s tariffs are lose-lose, a concept that is counter-intuitive to those who favour the misleading metaphor of a war. Mr Trump tweeted: ‘When you’re almost 800 Billion Dollars a year down on Trade, you can’t lose a Trade War!’

Repeat after me, Mrs May should say: there is never any winner in a war, just different degrees of loser. He continued: ‘The US has been ripped off by other countries for years on Trade, time to get smart!’, citing the trade deficit as evidence of this exploitation. But a trade deficit in goods is usually a sign of a country that is good at selling services and attracting capital investment. P. J. O’Rourke put it best: ‘Imports are Christmas morning; exports are January’s Mastercard bill’.

Don Boudreaux, professor of economics at George Mason University, reminds us that the case against tariffs is not for the sake of the world, but begins at home: ‘When a government obstructs its citizens’ access to goods and services that these citizens wish to purchase with their own money, that government makes its citizens, as a group, poorer. And the fact that the goods and services in question happen to be offered for sale by foreigners does absolutely nothing to alter this reality.’

If people in Kentucky buy more goods made in Wisconsin than vice versa, nobody’s ripping anybody off, any more than if the inhabitants of Nether Wallop shop more in Stoke Poges than vice versa. It’s no different across international borders. It is a mystery to me why America has lurched so often into mercantilist and protectionist actions when it has the spectacular example of its own internal market to hand.

As the economist Doug Irwin put it last week, ‘Trump thinks about trade in these zero-sum terms, about whether there’s profits or losses, and he views exports as good and imports as bad.’ Such pre-modern, mercantilist thinking is about as outdated as the 18th-century belief in phlogiston. Step away from the tariff button, Mr Trump.

Matt Ridley is the author of The Rational Optimist.