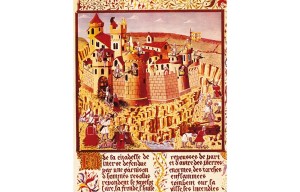

In the 13th century, having overrun and terrorised Europe as far as Budapest, and in the process possibly bringing with them the flea which caused the Black Death, the heirs to Genghis Khan and the Golden Horde had also conquered territory to the east as far as the Korean peninsular.

The assiduous Swiss scholar and explorer Christoph Baumer chronicles the ensuing sagas of the remaining individual khanates in great detail. But by the 16th century it is clear that although a few pockets still flourished, producing impressive buildings and works of art, these erstwhile mighty nomadic clans had sunk to a point where they had disappeared from the consciousness of the outside world. Even their devastating expertise as equestrian bowmen had diminished under the overwhelming technology of firearms and cannon.

This decline changes in the late 16th century, when Russia’s territorial ambitions expanded, motivated partly by its Romanov tsars’ quest to acquire a safe warm-water port — a desire still relevant in Syria and the Horn of Africa today — but primarily by sheer greed. Trappers and hunters began a concentrated move eastwards into Siberia, lured by ‘soft gold’, the skins of the sable, ermine, black fox and marten. Once these wild animals were wiped out, the trappers moved into new territory and then turned south-east towards Central Asia. Cossack soldiers, attracted by the prospect of rich agricultural holdings, followed the hunters.

The Manchurians (from China) became greatly disturbed, and demanded that the Cossacks’ fortresses be destroyed. Conflict ensued and Central Asia became, for the first time, a scene of armed conflict between two non-Central Asian great powers. Great Britain too, which after the defeat of the French by Nelson at Aboukir and Trafalgar had become the world’s paramount maritime power, was worried about the Russian search for a warm-water port. But the expansion by Russia into Central Asia caused far greater concern when their push extended south towards British India.

This was the start of the Great Game, and it is here that Baumer really gets into his stride. His canvas is huge, even embracing Afghanistan and Britain’s and Russia’s travails and defeats in that age-old deathtrap for foreigners. As ever with this series, there are magnificent photographs, maps and prints, and while the machinations of the Great Game are not covered in the same detail as by Peter

Hopkirk — who could better his account? — Baumer’s exciting narrative is meticulously backed by hard facts.

After 1917, most of Central Asia disappeared behind the Iron Curtain. I wish the author had given more space to Baron Roman von Ungern-Sternberg, the ‘mad baron’ who, as a White Russian, conquered Mongolia with a cavalry army and ruled that country from 1919 for almost two years before the Reds shot him and took over Outer Mongolia in the 1920s. This psychotic, violently anti-Semitic scion of an ancient Teutonic aristocratic family, killed people at whim, but was worshipped as a god by the Mongols after he defeated a Chinese warlord intent on acquiring huge chunks of their country. Yet during Sternberg’s reign of terror he introduced tarred roads and electricity to Mongolia. It can be argued that, had it not been for him, Outer Mongolia would have come under the sphere of influence of China.

‘We are the filling in a sandwich,’ I was told by a Mongolian foreign minister. ‘Russia and China are the bread on the outside. Both are bad for us, but if we have to choose, we will always choose Russia.’

In the late 1930s, Stalin destroyed over 800 of Mongolia’s monasteries and, Baumer states, ‘94,000 monks were displaced to the laity’. Unfortunately, a huge percentage of those 94,000 monks were dispatched to their maker. On Stalin’s direct orders they were lined up and shot on a quota system. Hardly a family in Mongolia was untouched by this horrendous slaughter — yet still the foreign minister preferred Russia.

At the same time, further south in Xinjiang, China, Ma Zhongying, a brilliant young Muslim Chinese general, fought to avenge Han Chinese slights against Islam and to keep out the Russians. Making incredible journeys on his grey stallion across the waterless Gobi, he nearly seized power (and did seize the Swedish explorer Sven Hedin).

Later, in the early 1940s, Kazakhs migrated across the Gobi in an attempt to reach Lhasa with their flocks and escape the conflict between the Communists and the Kuomintang. Some of the old men who undertook this journey explained to me how they had taught their horses and camels to eat flesh in areas where there was no vegetation whatsoever.

This book brings us up to the present day — Donald Trump even gets a mention in the index — and the emergence of the newly independent ‘stans’ and their growing influence and economic power acquired through mineral wealth. It brings to a triumphant conclusion Baumer’s majestic History of Central Asia. I cannot see how this four-volume series can ever be bettered.