All my life I’ve wanted to compose music, and now I’ve done it. I’ve written a sonata for solo flute that boasts two highly original features; it’s five hours long and must be performed by a badger.

Though it took me only five minutes to write, my opus one is guaranteed to get through to the second round of the next competition for new composers sponsored by Sheffield University and the Centre for New Music. That’s because they operate a ‘two ticks’ policy, as the Scottish pianist Philip Sharp — possibly the only classical musician in Britain who calls himself a classical liberal — revealed in his blog earlier this year. This is how they describe it:

A ‘two ticks’ policy will be in place for female composers, composers who identify as BME, transgender or non-binary, or having a disability, to automatically go through to the second stage of the selection process.

I don’t tick the female, BME or disabled boxes. I’m not going to insult transgender people by slipping into a cocktail frock for the duration of the competition. But non-binary? No problem. I’ll just insist on being referred to as ‘they’ rather than ‘he’.

Sharp describes this policy as ‘staggeringly patronising… Composers who happen to belong to one of these select groups are given a pat on the back and a snide helping-hand by virtue-signallers of the worst kind.’

It’s not surprising, however. If you’re looking for virtuoso virtue-signallers, then classical music is the place to start. But right-on competitions are merely the gruesome fruit of something more deeply rooted: an intellectual culture poisoned by late 20th-century identity politics and postmodern verbiage. That’s a problem in other disciplines, of course, but at least artistic and literary pseuds attract mockery. It flourishes in university music departments because no one gives a toss what happens there.

From time to time we glimpse what’s going on. Two years ago, Norman Lebrecht’s Slipped Disc website discussed a book called Just Vibrations by William Cheng of Dartmouth College, an Ivy League university in the grips of the cult of diversity and guff. ‘Working at the crossroads of critical inquiry and public engagement, I advocate for interpersonal care as the heart of academic and activist labors,’ he says on his Dartmouth page.

Just Vibrations regards ‘adversariality’ in musical scholarship (i.e. vigorous debate) as organised humiliation comparable to the bullying that causes teenage suicides. Cheng is a big fan of Susan McClary, the musicologist who discovered ‘the throttling murderous rage of a rapist’ in Beethoven’s Ninth — and claims that Schubert reveals his (completely undocumented) homosexuality through the ‘oblique modulations’ of the Unfinished Symphony.

This is the epistemology of the retired engineer determined to prove that the Egyptians built Stonehenge. Handel has been subjected to similar treatment. Gary C. Thomas, writing in the anthology Queering the Pitch, gets round the lack of evidence by suggesting that instead of focusing on the composer’s biography we should consider ‘Handel’ in inverted commas as a ‘(homo)text’.

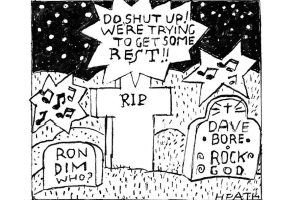

Lebrecht presumably had this sort of gibberish in mind when, in a recent interview with Van magazine, he denounced musicology as ‘a phony discipline… like parapsychology. It’s a cultish thing which makes up its parameters as it goes along.’

Cultish is right: like certain fringe religious movements, the new musicology attracts not just talentless opportunists but also the brightest young minds. William Cheng won a Stanford competition playing Rachmaninov’s Third Piano Concerto. He can write beautifully but chooses not to, stuffing his sentences with the rhetoric of victimhood and playing the silly typographical tricks that go with it: one of his topics is ‘d/Deaf cultures’. Worse, he wants to shut down debate.

If Cheng, with his Harvard doctorate, can succumb to bullshit theories and enforce leftist dogma, what hope is there for British university students who encounter classical music only under the umbrella of ‘cultural studies’?

The pianist Ian Pace, a dazzling interpreter of modernist composers such as (radical gay) Michael Finnissy, despairs of the ‘sustained assault on Western classical music from some academic quarters’. He’s calling for the teaching of core musical skills in British state schools — in other words, for music to be taught as music, rather than as social history or as an exercise in building self-esteem.

That’s exactly what should happen, but won’t. It’s now over 40 years since Britain had a prime minister who could talk intelligently about Bach or Bruckner. Our politicians and their civil servants long ago lost interest in music education and are happy to leave it in the hands of jargon-obsessed social engineers. As a result, any campaign to revive the Western musical canon will fall on d/Deaf ears.