Jazz may be an egalitarian, collaborative music, but jazz musicians honor their best with the laurels of hierarchy. Everyone knows the royal monikers of ‘Duke’ Ellington and ‘Count’ Basie, and most people know that Billie Holiday was ‘Lady Day’. But there’s also a whole aristocracy of hip name-drops: ‘The Baron’ (Charles Mingus), ‘Pres’ (Lester Young), ‘The Court Jester’ (Ornette Coleman), ‘The High Priest’ (Thelonious Monk). The list goes on, and on.

The mid-century saxophonist Hank Mobley (1930–86) was never ennobled in such fashion — unless you count Dexter Gordon’s hilarious handle for his friend, ‘The Hankenstein’. Nor has historical consensus enshrined Mobley as a leading musician of his era. Fellow tenor saxophonists like Sonny Rollins, John Coltrane, and select others are more popularly known and historically regarded. But among musicians, the two words used most to describe Mobley are ‘overlooked’ and ‘underrated’.

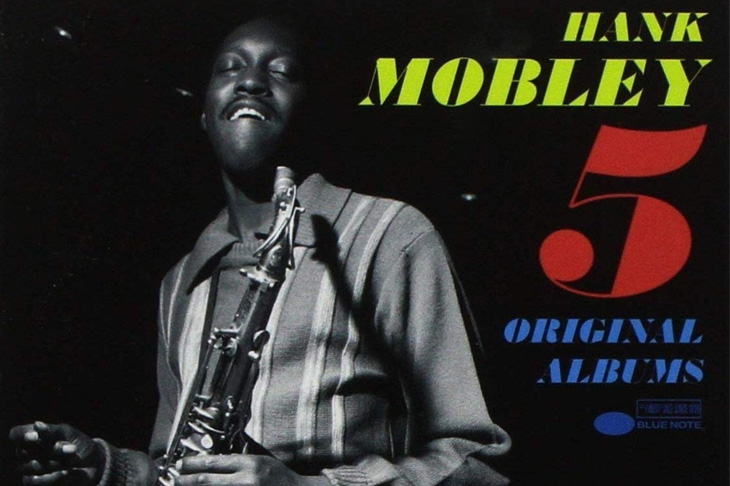

Perhaps it’s time, if not for revolution, to shake up the old order with the creation of a new musical dukedom or baronetcy. This week, Blue Note Records, the jazz label known in the ’50s and ’60s for its creative hospitality and its iconic album covers, releases a new CD box set of five albums with Mobley as leader: Peckin’ Time (1958), Roll Call (1960), Another Workout (1961; released 1985), No Room for Squares (1963), and Reach Out! (1968). These recordings, along with the 17 other albums Mobley recorded as a leader for Blue Note in the 17 years between 1955 and 1972, establish the saxophonist not only as a remarkably consistent performer, but also one whose career speaks to the power of creative integrity over conceptual novelty or popular appeal.

Hank Mobley was born in Depression-era rural Georgia but raised in Elizabeth, New Jersey. In 1946, aged 16, he picked up a saxophone and taught himself theory and harmony from books that his grandmother bought for him. By 19 he was playing in local R&B bands, and he soon began working with jazz greats such as Gordon and Lester Young, who visited nearby Newark for gigs. Through playing in Newark, he met the pioneering bebop drummer Max Roach, with whom he played intermittently for two years, and Dizzy Gillespie, who also hired Mobley to play in his band.

In 1954, Mobley joined Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, a new five-piece that included Blakey on drums, Horace Silver on piano, Kenny Dorham on trumpet, and Doug Watkins on bass. The group, led nominally in its early years by Silver and Blakey, is widely held to have founded the new genre, ‘hard bop’, a response to both the cushy pleasantness of West Coast jazz and the introverted intellectualism of New York bebop. The name ‘Messengers’, with its evangelical overtones, hints at the inflections of gospel and blues that would give hard bop its audience-friendly flavour. No more beatnik berets and professorial pipes — with hard bop, swing was most definitely the thing.

Mobley embodied the budding hard bop scene. Leaving the Messengers in 1956, he embarked on a remarkably prolific recording and composing career, and became a solid fixture of Blue Note’s sessions. Even in his earliest recordings, Mobley seems to have already come upon a sound that was all his own — bluesy but not clichéd, soulful but smart, and with little of the caustic bark with which Rollins and Coltrane muscled out their improvisations. In the liner notes of the 1961 album Workout, critic Leonard Feather named Hank Mobley ‘the middleweight champion of the tenor saxophone’. The praise might seem backhanded, but Feather intended the ‘middleweight’ designation to describe the tonal balance of Mobley’s sound — not too brazen, not too ‘cool’ — than the quality of Mobley’s imagination. As Mobley himself described it, ‘My sound is not a big sound, not a small sound, just a round sound.’

Just a round sound. Mobley, as these albums attest, is endlessly listenable. The lyrical approach to complex chordal improvisations, the ineffably lilting swing, the purring legato — Mobley’s voice is so natural that it takes listening to someone else to realise this isn’t how every sax sounds. It’s natural enough to put you at ease — enough to have tricked plenty of listeners into thinking that Mobley’s music is easy or simple. An unfortunate side effect of 20th century Modernism is that this sort of accomplishment doesn’t put you in the history books.

The years between 1958 and 1961 were Mobley’s most creative and productive. This period, though dotted with breaks of inactivity caused by drug dependence and a related incarceration, produced many of his finest albums, including Peckin’ Time, Roll Call, Workout, and 1960’s Soul Station — the album that may well be Mobley’s masterpiece.

Roll Call opens with an electrifying eight-bar drum solo by Blakey, who’s then joined by a gallery of indisputable hard bop greats: Freddie Hubbard (trumpet), Mobley, Wynton Kelly (piano), Paul Chambers (bass). As original members of the Jazz Messengers, Blakey and Mobley were familiar bandmates, and it shows. Mobley’s distinctive swing—trailing the beat oh-so-slightly, but always sitting snugly in the ‘pocket’ of the groove — is the perfectly balanced foil to Blakey’s forward-driving pulse.

In 1961, Miles Davis, struggling to find a replacement for John Coltrane, hired Mobley for his quintet. The career break was Mobley’s shot at immortality, but Miles was dissatisfied with the addition: ‘playing with Hank just wasn’t fun for me; he didn’t stimulate my imagination’. This bullet to the heart, and from the ‘Prince of Darkness’ himself, has popularised a negative perception of Mobley’s aesthetic as conservative, cautious, boring, and completely incompatible with the progressive aesthetic movements of the 1960s.

To be sure, unlike Trane and Miles, Hank was uninterested in forging the sorts of conceptual paths that the Sixties required of the artist interested in remaining ‘relevant’. While Coltrane pursued his meditative metaphysics and Miles went fusion-electric, Mobley largely stuck to his hard bop guns. Now, however, Mobley’s ‘stubbornness’ sounds like a virtue, and central to the sustained quality of his recordings. When he did on rare occasion yield to the pressures to conform, as in 1968’s Reach Out!, the results were heartless.

Reach Out! takes its name from its opener, a cover of ‘Reach Out (I’ll Be There)’, which had been a Motown hit for the Four Tops in 1966. Mobley’s rendition crawls along in agonising lethargy, and with none of the excitement of the original. But notwithstanding these uncommon slip-ups, Mobley’s tenure as a Blue Note hard bopper is testament to the enduring fertility of a musical tradition that found itself under siege during the cultural upheaval of the Sixties and Seventies.

Mobley now also suffered from increasingly bad health. The title of 1972’s Breakthrough!, recorded with the pianist Cedar Walton, proved naively optimistic — it is Mobley’s last studio recording. Lung problems, a death knell for any horn player, forced him into early retirement in the mid-Seventies. Stripped of his ability to make money by playing gigs, and struggling to profit from his recorded legacy, Mobley fell into poverty.

‘Hank was a very prolific writer,’ the saxophonist Gary Bartz told Jazz Life magazine in 1995, ‘but most of his songs were in different publishing companies, they’re all over the place and he just didn’t know how to get his money, even though he really needed it. At the end of his life, Hank was homeless; he was living in the Amtrak station in Philadelphia.’

Mobley died of pneumonia on May 30, 1986, age 56 — just as the Eighties’ jazz revival was getting under way, and just as Blue Note started reissuing his albums on CD. The moment is ripe for a comprehensive revaulation of this near-forgotten artist’s legacy. Give these Blue Note records a listen. Our friend The Hankenstein is as alive as ever, a prince among players.

Andrew L. Shea is assistant editor of The New Criterion. He is also a painter and plays upright bass.