No one any longer denies the immense significance of Wagner’s musical-dramatic achievement, even if they find it repellent. But his reputation as a writer — of operatic texts, autobiographical and biographical memoirs, practical essays on how to conduct particular pieces, vast and less vast theoretical works, ranging from speculations on opera and climate to theologico-political musings — is not high. Nor should it be, except for the more ‘occasional’ pieces.

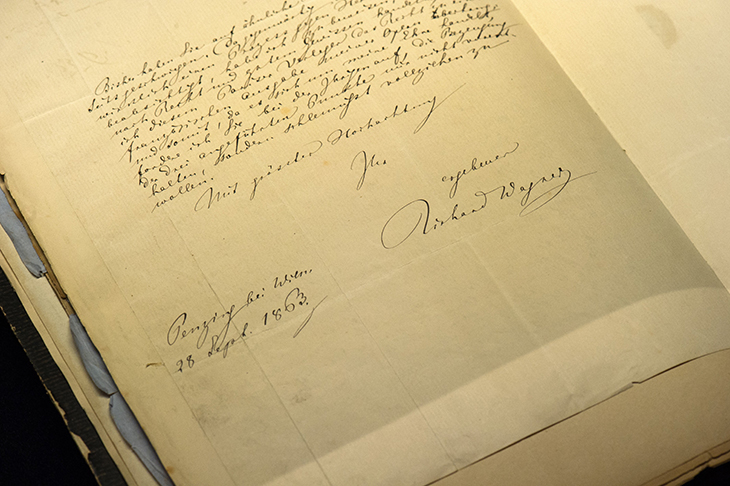

He was in fact a major contributor to mauvaises lettres, and no kind of systematic thinker, however much he might have liked to be. His only prose that is consistently readable comes in his letters, some of them enormous, all of them full of life and colour. Many of the 12,000 he is known to have written survive, still being edited in the German edition. His complete prose works have been translated into English only once, by the dauntless and mad William Ashton Ellis, and although everyone who mentions Ellis’s work rightly deplores it, no one can face the prospect of doing the job again. Shorter essays and stories, occasional pieces such as his essay on Beethoven (recently and admirably edited and translated by Roger Allen), are all that we can hope for, or should feel the need of. The relationship between his ‘thought’ and his operatic practice is as wayward and dubious as it is in the case of any major artist.

When it comes to the texts for his dramas, the situation is quite different. His own estimate of his poetic gifts varied, but he was, with very small exceptions, a consummate dramatist. When one contemplates the four-part drama of Der Ring des Nibelungen, for instance, and compares it to the multifarious sources in Teutonic and Nordic myth and legend from which he extracted and remade it, no degree of admiration is adequate. The same certainly goes for Tristan and Parsifal. Not only the shaping of his ‘poems’, as he always called them, but also the language in which he couched them, are amazingly flexible and — vitally — singable. He is often taunted, especially by his countrymen, for his archaisms, occasional neologisms, inversions and alliterations. I’m not the best person to judge, but it seems to me that much of the time he was writing words with music in mind, even if what the music was to be had not yet been hit upon.

What is clearly the case is the different resources of language that he employed for his various dramas. The Ring is typically written in short lines, with plenty of alliteration, while Parsifal, as befits its largely contemplative, exalted nature, is mostly written in long, non-alliterative lines. As for the archaisms, etc., Wagner felt, as did many writers in the 19th century, that in evoking myths and recreating them, a language that was at some distance from contemporary idioms was desirable.

There have been numerous translations of his dramatic texts into English, beginning with ones that appeared shortly after the works were first performed, and continuing to the present day. During that distant time when record companies issued lavish boxed sets of the operas with large booklets included, one could count on a full translation alongside the German text. Usually the translations were functional but indispensable. This was before the age of surtitles and DVDs with subtitles, the biggest step forward in operatic history of the past 50 years.

Then came The Ring in English under Reginald Goodall, and, for that momentous series of occasions, a new translation of the text, singable and audible, was required. Andrew Porter rose magnificently to the occasion, as John Deathridge, in his new translation, handsomely acknowledges. That translation has been used throughout the English-speaking world, and was independently published by Faber. Of course, in making it singable Porter had to take liberties, for which no one blamed him.

Then came Stewart Spencer, with a magnificent and more literal translation, including — its most valuable feature — the variant texts that Wagner modified or discarded over the years. That is especially important in relation to the final scene of the whole work, which Wagner subjected to constant and drastic modification. How does The Ring and hence the world end? He found it almost impossible to decide. It was even one of the two occasions when his wife Cosima interfered and told him that some lines should be omitted because they were ‘too artificial’ — and she was right. Spencer’s version, with essays of varying quality by Barry Millington and others, is for me the indispensable one.

Now comes the new translation by John Deathridge, doyen of English-speaking Wagner scholars, with a grasp of his life and writings that may never have been equalled. In a stoutly bound Penguin Classic, he offers the whole text of The Ring as it was set to music, and includes many remarks that Wagner made while the cycle was being rehearsed for its first performances in Bayreuth in 1876. Deathridge used to be a sceptical Wagnerian, but now he has nothing but praise, especially for the texts. He quotes Nietzsche: ‘Earthiness of expression, reckless terseness, control and rhythmic diversity, an extraordinary richness of powerful and significant words, the simplification of syntactical constructions, an almost unique inventiveness in the language of surging feeling and presentiment’ etc., etc., and agrees with it all. Well one might, and Deathridge sets out to translate The Ring so that anyone reading the English version will agree: and in that noble enterprise he seems to me to be entirely successful.

As I read through all the right-hand pages in this volume, and from time to time looked over to check the German, with which I’m obviously far more familiar, I was struck once again by amazement. Wagner wrote the whole text — in half-part backwards, as we know — and then, after some perfunctory attempts to set it to music, left it for several years, then got under way and wrote more than two thirds of it, followed by the famous 12-year gap. Most of the material that appears in the ‘preliminary evening’ reappears in the final drama Götterdämmerung, composed when he was really an enormously different artist — yet both the text and many of the ‘motifs’ of Das Rheingold still served for the mighty conclusion. It’s hardly possible for us now to read the text and not think instantly of the music for it, but Wagner can have had no idea whatever how he was going to set it. ‘Awesome’ is a word I detest, but how else can one describe that?

Deathridge has opted for an idiom which is not, in general, as dignified as the original, and verges on the slangy. When, in Die Walküre, Wotan is about to condemn Brünnhilde to her fate, Deathridge gives us ‘Don’t get any ideas, young woman, about shaking my confidence’, while Spencer opts for ‘Don’t strive, O maiden, to alter my mind.’ I prefer the latter, with ‘strive’ giving a mildly archaic feel. But really both translations are admirable. Yet while Deathridge gives us occasional remarks made by Wagner during rehearsals, he doesn’t give the alternative or eliminated passages that are so interesting. And in his introduction Deathridge, determined to keep things short, ranges over so much ground so rapidly, and often in a ten-thumbed prose style, that I would have preferred twice the length and half the concentration. Still, this is a handy, beautifully presented and authoritative volume, which can only — unlike all contemporary productions of The Ring — cast light on this inexhaustible masterwork.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.