Lewis loves Rachael. Rachael loves Lewis, but she’s not sure if he still loves her. Stephen the handsome widower loves Rachael on sight. Stephen and Rachael have an affair. What happens when Lewis finds out?

This plot will be familiar to all practitioners of suburban adultery. It will also be familiar to those students who, rather than taking their pleasure quickly on the kitchen table like Stephen and Rachael, have read Anna Karenina. It is also the plot of The Aftermath, a tastefully muted mishmash of interior design, Nazi fetishism and war guilt, enlivened by that unacknowledged innovation of the World War Two era, the key party.

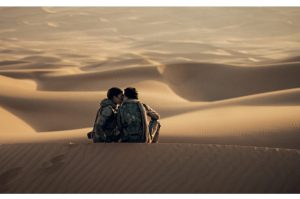

It’s the winter of 1945. The victorious Allies have divided Germany into zones of occupation: American British, French, Russian, erogenous. Lewis (Jason Clarke) is an officer in the British sector, in the ruins of Hamburg. Lewis feels sorry for the Germans, for reasons that the script doesn’t bother to explain. When his wife Rachael (Keira Knightley) joins him, they are billeted in the erogenous zone, a massive suburban villa with Stephen (Alexander Skarsgård) and his teenage daughter Freda (Flora Thiemann). Insisted of expelling Stephen and Freda, Lewis asks them to stay. The German victims of war move into the attic, while the British oppressors get the master bedroom.

Stephen is a good German, and even better in bed. Still to receive his certificate of de-Nazification, he insists that he was never a Party member. We believe him. By the looks of it, he spent most of the war in the gym, sculpting his abs. The villa was his wife’s; her family owned shipyards. She was killed when the RAF bombed Hamburg. Stephen gives Lewis a tongue-lashing about this, and Lewis, admitting his war guilt, accepts it. When Lewis is called away to the Russian sector for a few days, Stephen gives Rachael a good tonguing too.

The aftermath in this film’s title is supposed to be the ruins of Europe’s cities, but really, it’s the sentimental ruins of our therapeutic culture. All the postwar elements are here, but this isn’t The Third Man. Instead of the location acting on the characters or the plot, the characters act amid the location. The war is just window dressing, its nastiness a way of catching our attention in the occasional interludes when Keira Knightley is fully clothed. The dialog is more wooden than the forests of Bavaria, and the characters’ motivations are those of our time.

If you’ve ever read the disheartening, heartless document that is a how-to guide to script-writing, you’ll know that the bare minimum for soap operatic character development is the placing of an obstacle in front of a character. As the character surmounts the obstacle, the plot is carried forward, and this development produces in the audience the psychological release that the old-time screenwriter Aristotle called ‘catharsis’.

The Aftermath is adapted from a novel by a soap opera scriptwriter, Rhidian Brook. It is directed by a veteran perpetrator of low-grade television, James Kent. It would take a heart of stone and a head of cheese to apply the trivialities of light entertainment to people whose lives have been ruined by war, but Brook and Kent pull it off. Their characters’ obstacles are grief of the nastiest and most gratuitous kind.

Rachael and Lewis’s 11-year-old son was killed by a German bomb. Stephen’s wife, and Frieda’s mother, was killed by a British bomb. If you believe this makes Lewis and Stephen are morally equivalent, Stephen has a labor camp in the East for you. Lewis blames Rachael, and Rachael is angry because Lewis was too busy at the office — sorry, too busy fighting the Germans. Frieda is angry at Stephen, and Stephen is angry at both Lewis and Rachael. Stephen is much hotter and posher than Lewis, who is so stricken by war guilt that he has let his gym membership lapse. This is good for all concerned, because it allows all parties to surmount their obstacles, shoulder the plot, and stagger forward like they’re in a boot camp for Oprah Winfrey’s stormtroopers. The moral is, no loss is too great to surmount. It’s a triumph of the will.

Rachael first discovers her latent hotness when reclining on a Mies van Der Rohe chair, a posturepedic symbol of Germany’s super-sexy blend of modernity and perversion. Stephen, being the proprietor of said Bauhaus sex seat, is already in touch with his perving hotness. It doesn’t take long before he’s all over Rachael’s hotness too. When she runs away with Stephen, war criminal Lewis accepts the gift of cuckoldry, falls to his knees, and sobs aloud. When you see The Aftermath, you’ll know how he feels.

Dominic Green is Life & Arts Editor of Spectator USA.