Churchill must be the most written-about figure in public life since Napoleon Bonaparte (a subject, incidentally, to which Andrew Roberts has already contributed a substantial and prize-winning biography). As the publisher obligingly warns us, there have been over 1,000 previous studies of Churchill’s life, including some dross, but many works of serious importance. To add anything worthwhile to this mountain requires that the author should be determined, courageous and have something new to say. No one has ever doubted Roberts’s determination and courage; the question remains whether he has anything new to say.

Rather to my surprise, the answer has to be ‘yes’. Roberts has been assiduous in his research. His list of acknowledgements is formidably long, even extending to Janina Gruhner, of Zurich University, who showed him ‘the podium Churchill spoke from in 1946’. He does not seem, however, to have had exclusive access to any new source of great importance. The considerable merits of this book depend not so much on the novelty of the material as on the perception, good judgment and imaginative understanding of the author.

The Churchill he depicts is far from being entirely admirable. He was ambitious and often offensively self-confident. When he was 35, Asquith offered him promotion to the post of Chief Secretary of Ireland. Almost anyone else would have grabbed at the opportunity; Churchill replied that he would prefer to go to the Admiralty or the Home Office. He got away with it and secured the latter post. By his arrogance he must have known that he was imperilling his political career, yet there is no reason to think that he hesitated for a moment. More than most other statesman of the period — perhaps of any period — he was convinced that he was destined to succeed. Of course there were moments of doubt and self-questioning, but they counted for little compared with his immense self-confidence. He saw things almost entirely through the prism of his own self-absorption. The first world war for him meant not suffering and bloody carnage but adventure and the prospect of personal advancement. ‘I would not be out of this glorious, delicious war for anything,’ he told Margot Asquith in 1915. ‘I say, don’t repeat that I said the word “delicious”,’ he added nervously, realising that he was going a little too far, but it was the right word to describe his attitude all the same.

‘It is said that famous men are usually the product of an unhappy childhood,’ Churchill remarked in his biography of his ancestor, the Duke of Marlborough. Churchill was himself already famous — or had at least attained considerable notoriety — by the time he wrote that book. Was his childhood therefore unhappy — or, at least, did he himself believe that it had been so? The second, certainly; the first, perhaps not so much, but his circumstances were far from ideal. He had a younger brother, but Jack was born some six years after him and the two were never close. To all intents and purposes, he was an only child, with all that that implied by way of loneliness and boredom. Like most upper-class and upper-middle-class children of the time he was largely ignored by his father. His mother, Jennie, paid slightly more attention to him but her hectic social life meant that she did not have much time to spare for a child, especially for one who was often unappealing and sometimes rebarbative. ‘She shone for me like the evening star,’ wrote Churchill many years later. ‘I loved her dearly — but at a distance.’ Stars are nice to look at but they offer little by way of comfort. The most important figure that featured prominently in his life was his nanny. ‘My nurse was my confidante,’ he continued. ‘It was to her that I poured out my many troubles.’ The troubles might not have been particularly significant, but to a lonely small boy they must at times have seemed overwhelming.

One of the problems about writing a biography of Churchill is that he has done it all himself already with unmatchable vigour and eloquence. His historical details were sometimes unreliable, and impartiality was not a quality which ranked high in the roll-call of his virtues, but the 50-plus volumes which Roberts credits to Churchill in his bibliography cover in rich detail every aspect of that amazing life until close to the very end. Any biography must, of course, absorb and reflect that material, but the author must not let it overwhelm him. Roberts passes that test successfully: he never lets the reader forget that this is Churchill as judged objectively by an outside biographer, not as Churchill himself would have seen it and have sought to impose that vision upon the reader.

But though Churchill would have disputed many of Roberts’s judgments and undoubtedly proposed some substantial re-drafting, even he would have conceded that it is on the whole a generous portrait. ‘With enough spirit,’ Roberts concludes, ‘he believed that we can rise above anything, and create something truly magnificent of our lives. His hero, John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough, won great battles and built Blenheim Palace. His other hero, Napoleon, won even more battles and built an empire. Winston Churchill did better than either of them: the battles he won saved Liberty.’ If, in some after-life, Churchill is reading this peroration he might be wondering: ‘Could I have put it better myself?’ Since, however, he habitually believed that he could have put anything better himself, it seems probable that his response would not be to the advantage of Mr Roberts.

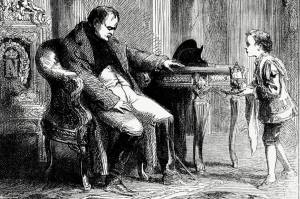

One book which does not appear in the list of Churchill’s writings is a biography of Napoleon Bonaparte. It was not for lack of interest. ‘I really must try to write a Napoleon before I die,’ he once told his wife. He never did. The two make an interesting contrast. That Churchill would have been the better company can hardly be doubted. He got fun out of life and made life fun for other people — ‘fun’ is not a word easily associated with Napoleon. Which was the greater man is more a matter of personal taste than of objective historical judgment. Churchill was born into a privileged sector of society, so he had an easier start, but if it had been he who had emerged from the Corsican backwoods it is hard to believe that he too would not have risen to some sort of eminence. Whether he would have gained absolute power, and if so, whether it would have had the deleterious effect that Acton prophesied, is an interesting but idle speculation. Churchill’s power was never absolute but for a while it was immense and in the second world war he used it with zest and concentrated vigour.

In another age the result might have been calamitous; Andrew Roberts leaves one in no doubt that, in the summer of 1940, it saved the world.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.