Eight centuries ago in Turkey, at a gathering of intellectuals, a Muslim sultan insisted that one of his courtiers write a book about an unlikely subject: thieves and con artists. The sultan, Rukn al-Din, had secured another such book from Spain, but he wondered: ‘What’s left out of it?’ The set-upon courtier was Jamal al-Din Abd al-Rahim al-Jawbari, and the commissioned Arabic work, Kashf al-asrar (Exposing Secrets), his only surviving text. But why would a powerful ruler such as Rukn al-Din, presumably safe from street-level scammers, order a guidebook about the medieval Islamic underworld?

The answer is most likely nostalgie de la boue — a way, as Tom Wolfe was to argue in Radical Chic, to assert superiority over the ‘middle-class striver’s obsession with propriety and keeping up appearances’. The Book of Charlatans wasn’t the first or last of its kind. Take the streetwise picaresque tales by al-Hariri in the 11th century, or the rip-roaringly grotesque plays of Ibn Daniyal in the 13th. Such elitist longing for the mud, however, wasn’t just in books. Rulers often held court with murky figures from the city’s underbelly. The 10th-century vizier al-Sahib ibn Abbad supported men such as Abu Dulaf, a shadowy traveller who wrote poetry about beggar thieves.

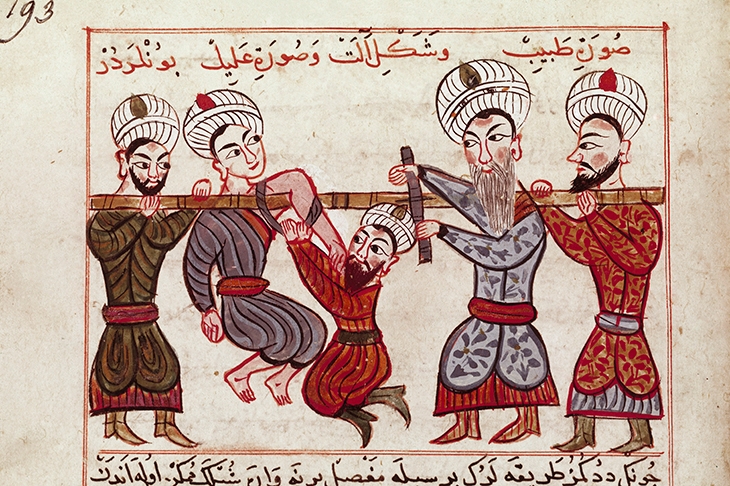

But unlike al-Hariri or Ibn Daniyal, al-Jawbari entices readers with purportedly real tips for avoiding fraudsters, divided into 30 chapters by type — ‘False Prophets’, ‘Apothecaries’, ‘Conjurers’, ‘Notaries’ etc. Often their schemes rely on tricks of chemistry or engineering. Al-Jawbari warns, for instance, of grifters who feign blindness by sealing their eyelids shut with ticks’ blood and gum Arabic, or a false prophet who claimed to control live fish with his spiritual powers, whereas in fact he used a paste of basil and human feces to attract them. Al-Jawbari does not hide his contempt in these vignettes: ‘Wise up to their tricks!’ he repeats like a chorus. ‘Stay away from these vulgar sheikhs.’

He also reiterates a desire not to bore readers — though at times his own realism is so exhaustive as to risk the effects of the knockout drugs he describes. Entry after entry lists chemicals, powders and foods used for such stupefacients. ‘Blue henbane, poppy seed, opium, euphorbium, black seed, agarikon, lettuce seed, basil seed, mandrake apple and datura nut’ — these are the ingredients for ‘Blue Cretan henbane’, one of many sleep agents mentioned. For students of Islamic material history, such details make The Book of Charlatans a trove of data. For the rest of us, they make it a bit of a slog.

[special_offer]

But al-Jawbari’s sober style becomes (perhaps unintentionally) humorous when it encounters decidedly non-sober anecdotes. In a chapter on corrupt money-changers, he mentions the ‘ballsiest’ of them all: people who scam the money-changers and beat them at their own game. Elsewhere he mentions beggars who show up with a well-dressed monkey, which they claim to be a hexed human prince seeking money for an antidote. And in one of the more disturbing cases, he describes ‘those who work Solomon’s ant’, a group of swindlers who draw in unsuspecting young boys with the promise of an ant with a human face and mystic powers, only to ‘debauch them and make off with people’s money’.

These bawdy sketches were popular among elites, as the many surviving manuscripts and print editions of The Book of Charlatans show. But the fascination with crime seems to be universal. To tantalize audiences with the claim ‘based on true events’ is an old trick, whether in the Chinese court fictions of Judge Bao or the Victorian penny press. At some level, readers want it to be true, whether or not it is. And while Charlatans has the stamp of realism, you find yourself wondering about the line between fiction and fact — and about the author’s own stake in the venture.

In fact, al-Jawbari seems to practice the very things he warns against. A Gonzo journalist avant la lettre, he befriends a money-changer who reveals his tricks after al-Jawbari figures one of them out. He draws in a fire-manipulator by showing him ‘scientific feats that blew his mind,’ prompting a lesson in fireproofing. What if, even as it warns against charlatanry, The Book of Charlatans is itself a drawn-out confidence job? If so, then it is all too fitting for a favorite metaphor by al-Jawbari: ‘They keep him going like this, and by so doing turn him into a nice little pumpkin patch that they can crop.’

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.