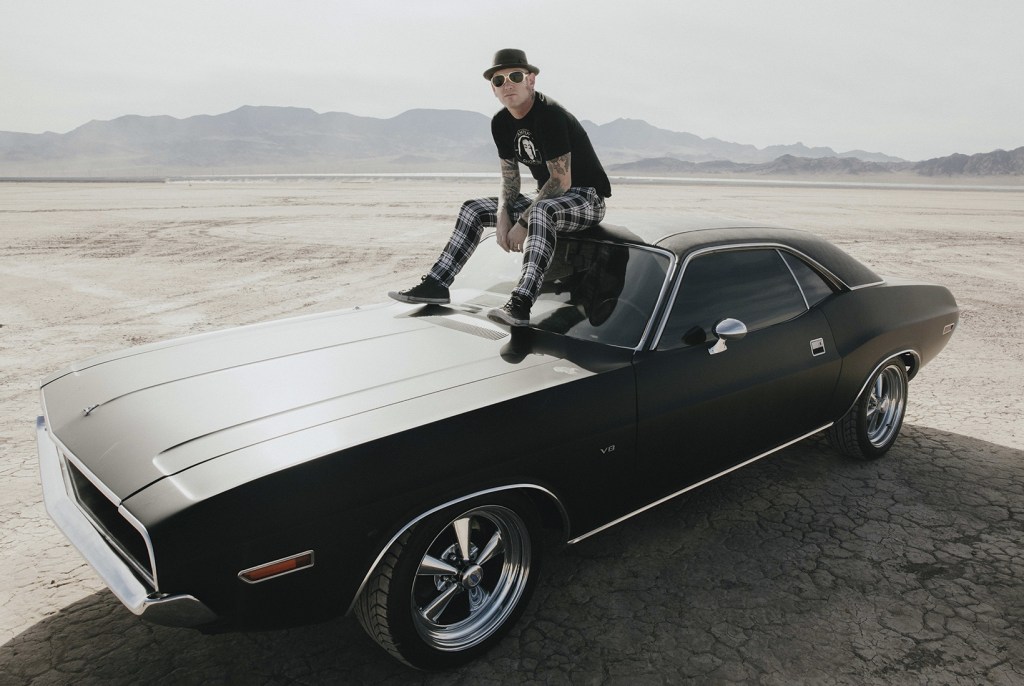

Corey Taylor, the singer of Slipknot, laughs when I observe that he is disappointingly well adjusted. He had just been explaining that he does his own cleaning at home, that he ‘hates seeing privilege and entitlement’, that he can get from place to place without needing his hand held (you might scoff, but many musicians get infantilized by a life of indulging and being indulged). ‘I have a very healthy ego,’ he says. ‘But I also know to keep it in check as much as I can, because I don’t want to be that dude.’

Which is not to say Slipknot’s career has been free of incident. Far from it. Though they have released only six studio albums over the past 21 years — the last three all US No. 1s — they’re the biggest metal band to have emerged since Metallica in the 1980s, headlining arenas and festivals around the world, and they achieved that by being anything but sensible and well adjusted.

The Daily Telegraph called them ‘the most revolting band in the world’; they were accused of inspiring murders in both South Africa and California; there was a bizarre incident when a grave robber left their lyrics at the scene of the crime; they’ve had one member die of a drug overdose; and they’ve been painted as a mortal threat to society. And, to be fair, their appearance — clad in horror masks and black leather — doesn’t make them look like people you’d want to take home to mother. Taylor himself was sexually abused as a child in Iowa. He was drinking at 11, and a heavy user of cocaine and methamphetamine by his mid-teens. By the time he was 18, he had tried to kill himself. ‘Let’s put it this way,’ he says. ‘I chose this life because of how dark it was.’

The darkness didn’t lift with fame. ‘My late twenties were very brutal. That’s when I was really in the depths of my alcoholism. I had to pull myself out, not just for myself, but because I’d just had my son. He was a year old and I’d pretty much missed the first year of his life because I was either touring or I was wasted. I didn’t want to be that man. I had missed the first 10 years of my eldest daughter’s life because her mom and I had broken up when we were young, and I was out on the road. But I knew I wanted to be a dad. Being that was much more important than romanticizing some addiction life. I didn’t want that. I took a long time to stabilize. It’s taken some adjusting.’

Taylor got sober some time in the 2000s, though exactly when is unclear — Google it and it’s a case of pick a year, any year. And with sobriety has come insane productivity. He’s talking to promote his first solo album, CMFT (a more conventional hard-rock album than Slipknot’s brutal noise), though neither of us bothers mentioning it. He’s made six with his other band, Stone Sour, acted in films and in Doctor Who, and written five books, though the achievement may be more in the labor than the product, judging by the reviews (‘Angry, self-aggrandizing, bilious and barely readable’).

Slipknot, though, is the source of everything that followed. What made them ‘the most revolting band in the world’ was that where metal had previously tended to treat darkness and malevolence as a backdrop, a pantomime, they didn’t. Taylor’s songs were inspired by his own experiences, and the violence in them felt threatening. ‘Older bands like Venom or Slayer or Mercyful Fate, they used the stylings of Satanism, which was almost quaint in comparison with what we were trying to talk about, which was inner turmoil, dealing with the PTSD from abuse growing up — these things are very much more visceral than those bands. For people who had never experienced that before, it was quite an alien world and they couldn’t understand why it was so cathartic. But from our side of the fence it was almost like a survivors’ circle, man. We were really just sharing and trying to move on.’

Taylor is now 46, and still singing the songs he wrote when his misery was his only subject. When he sings something like ‘People = Shit’ or ‘Surfacing’, is it now an act? Or do the traumas of his youth still trouble him? ‘No, no, they don’t. The great thing about making this music is that I’ve been able to make peace with a lot of the stuff that happens to me. Obviously there are still issues that cling to me, but that’s what therapy’s for, basically.

‘I don’t think I’m still muddled down with that sort of adolescent anguish. I don’t like to call it angst, because it’s a lot more than that because of my background and how gnarly my childhood was. But I also think that has made me who I am. It’s made me far more independent than I might have been. If you can’t be strong enough to deal with the reflection of an image, or a reflection of an emotion that is not nearly as intense as it was when you were first living it, then you’re not as far down the road as you think you are, let’s put it that way.’

Taylor likes to reflect on how his songs have helped those with similar scars, as Metallica’s songs helped him when he was a kid. That’s doubtless true in part, though never underestimate the appetite of teenagers for both horrible noise and people who look as if they have walked out of a horror movie. But it also underplays the fact that though Slipknot shows — like all metal shows — attract a bunch of teenagers, a good chunk of his crowd are in their forties now, like him. And that aging crowd raises another issue.

[special_offer]

Slipknot’s origins lie in exactly the kind of undereducated, alienated, marginalized, white, working-class Midwestern communities that, conventional wisdom holds, propelled Donald Trump to the presidency in 2016. Taylor has been far from shy about offering his opinions about Trump over the past four years, and they have been wholly negative. Given a substantial part of his audience, in the US at least, are the people who voted for Trump, does it ever cross his mind that many of his fans must despise his politics? ‘I think about it every once in a while. I only talk about it in interviews. I don’t pump a lot of those messages into my music. But at the same time, I’m not going to change myself just to try and sell albums. If you don’t like it, don’t buy my album. I’m not forcing you to do so.’

Being a rock musician always looks like the easiest job in the world — ‘Five years’ playing, 20 years’ hanging around’, as Charlie Watts once described the Rolling Stones — but it’s not a life I would choose, especially when it involves a show as physical as Slipknot’s (they are, so far as I know, the only band who have had one member nearly drown onstage in a dustbin. That was certainly not an issue for Peters and Lee.) ‘I’ve had spinal surgeries,’ Taylor says. ‘I’ve had double knee surgeries. I’ve gotten to the point where I work out just to stay a certain shape. I don’t even work out to look good. I just work out to stop looking like a potato with limbs growing out of it. It’s reality. I woke up the other day and I’d slept wrong, and a rib had popped out. That’s the reality of my life.’

He doesn’t sound awfully like a threat to society, really, does he?

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.