The Parade

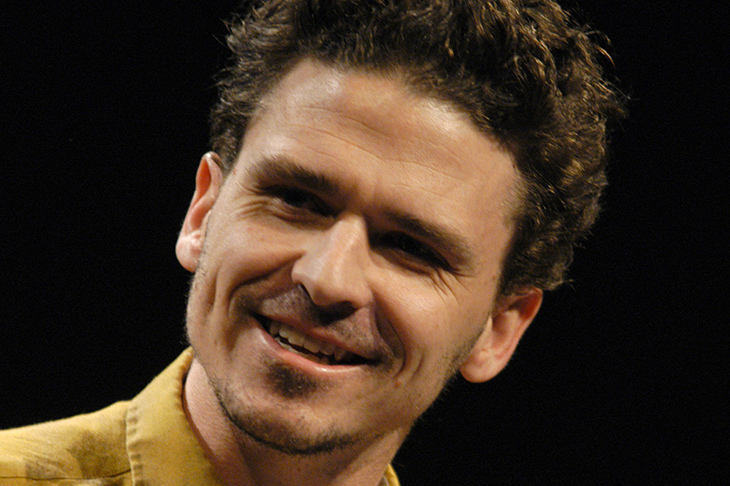

, Dave Eggers’s eighth novel, is a slim, strange book, another unpredictable chapter in the career of this hard-to-pin-down author. Like his friend and sometime collaborator Jonathan Safran Foer, there’s the sense with Eggers that, after launching himself so spectacularly onto the literary scene with his debut, A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, this is an author who hasn’t quite worked out what sort of grown-up writer he wants to be. His novels feel trapped in the no-man’s-land between avant-garde experimentation and straightforward realism, and while they often contain passages of strikingly stylish prose, there’s the impression that they don’t quite hang together as a body of work, that he’s still a novelist in search of an identity.

The Parade owes a great deal to J.M. Coetzee’s masterpiece Waiting for the Barbarians. Like Coetzee, Eggers has fashioned an unnamed country, presumably (although, tellingly, not explicitly) in Africa, where the protagonist’s physical and metaphorical journey functions as a commentary on the idea of progress. Like Barbarians, The Parade has a bien-pensant central figure whose organizing moral tenets are tested over the course of the story. It isn’t giving away too much of a powerfully affecting ending to say that, like the Magistrate in Coetzee’s novel, Eggers’s hero, known only as Four, ends up facing the limitations of the comforting pabulums of his world view.

Whereas the Magistrate is shocked out of his woolly progressiveness by recognizing his role in a brutal totalitarian regime, Eggers’s novel questions Four’s unexamined assumptions about the benefits of capitalism and globalization. The Parade is set in the near future and Four is the veteran operator of a hi-tech paving machine that lays pristine roadways, complete with markings. The vehicle, the RS-90, is owned by a shady multinational and has been hired out to the government of a country where a bloody civil war has recently ended. Four is to pave ‘230 kilometers of a two-lane roadway, uniting the country’s rural south to the country’s capital in the urban north’.

The RS-90, which moves at a stately four kilometers per hour, can deal with all but the most sizable of impediments, but Four is joined by Nine, whose job it is to scout ahead along the route on a quad bike, clearing the path of people and obstacles. Four, who’s grizzled and taciturn, immediately takes against Nine: ‘in an instant he knew Nine was an agent of chaos and would make the difficult work ahead far more so’.

Four is correct — if Four is the unthinking tool of neoliberalism, Nine is another problematic face of our interaction with the developing world. He speaks the local language, is keen to engage with the indigenous population, to eat with them, to sleep with their women. The novel is pinned resolutely to Four’s perspective — we know of Nine’s (mis)adventures only via his occasional reports to Four, who is an unwilling listener. It’s a lovely narrative device, to have the repressed, diligent Four pressing ahead along his straight path while the unreliable, manic Nine veers off on increasingly wild divagations.

This is a novel that shows us the subtle and invidious ways that narratives of progress have been hijacked by neoliberalism. Four believes utterly in the work he’s doing — ‘Once paved, the highway would be sublime.’ Nine sees himself as an enlightened global adventurer. Both view the road as a certain remedy to the country’s north/south divide, to the tensions that stoked the civil war. The pair anticipate the parade that will mark the completion of the project as a celebration of their own benevolent contribution to the country. The superb ending feels entirely earned, a fitting denouement to a novel whose morality is dazzlingly complex and whose conclusions are never simple. Certainly his best book since What is the What, The Parade may well be the sound of a major writer finding his mature voice.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.