Watching Rod Serling’s Twilight Zone was like a narcotic experience. The poetical monologue took you into a dimly-lit room, on the crackling leather of a worn couch, into thick plumes of cigarette smoke. Smartly suited, Serling introduced a flaw in the human condition in a rhythmic, jazzy voice, as if he were about to whip out a horn and blow the smoke away to reveal a moral, a twist, or riddle. Through 156 episodes, The Twilight Zone was as much a literary as a celluloid achievement.

Remember ‘The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street’ from 1960? A parable of McCarthyism, and a mowing of the lawns of suburban paranoia. ‘The tools of conquest do not necessarily come with bombs, and explosions, and fallout,’ Serling intoned. ‘There are weapons that are simply thoughts, attitudes, prejudices, to be found only in the minds of men. For the record, prejudices can kill and suspicion can destroy…’

The struggle between the solipsistic leftist artist Sterling and the conservative executives at CBS restrained The Twilight Zone from wandering into the dull and petty terrain of propaganda. The Twilight Zone was a collection of short stories, not a long-form literary allegory. Each episode was its own kind of adventure, a delicious cocktail which never imprisoned the viewer in a myopic philosophy.

Jordan Peele has extinguished this format. Peele and his crew use The Twilight Zone to present a progressive allegory of the Trump era, which handcuffs it to the present or the near future. In the second episode, ‘Nightmare at 30,000 Feet,’ investigative journalist Justin Sanderson peruses magazines depicting characters from upcoming and previous episodes. One has the face of a spoiled child running for president.

This Mad magazine parable of Trump replaces the warm bath fantasy with a cold shower. There are no conservative executives in today’s ideologically homogenous Hollywood. Freed from supervision, Peele and showrunner Glen Morgan lack creative restraint, their #Resistance tendencies creeping in. Serling was denied the creative control to use television as a social justice commentary schoolroom, and this prevented The Twilight Zone from being a self-righteous anthology of his personal activism. Peele operates like a progressive propagandist with a mandate to use art to attack white privilege, as he sees it, and fulfill the agenda of his movement — which isn’t humanist, but ‘woke.’

He’s the the Frank Capra of the far-left. ‘The parable is the most effective form of communication,’ Peele told Gizmodo in March. ‘It beats lecture, it beats everything.’

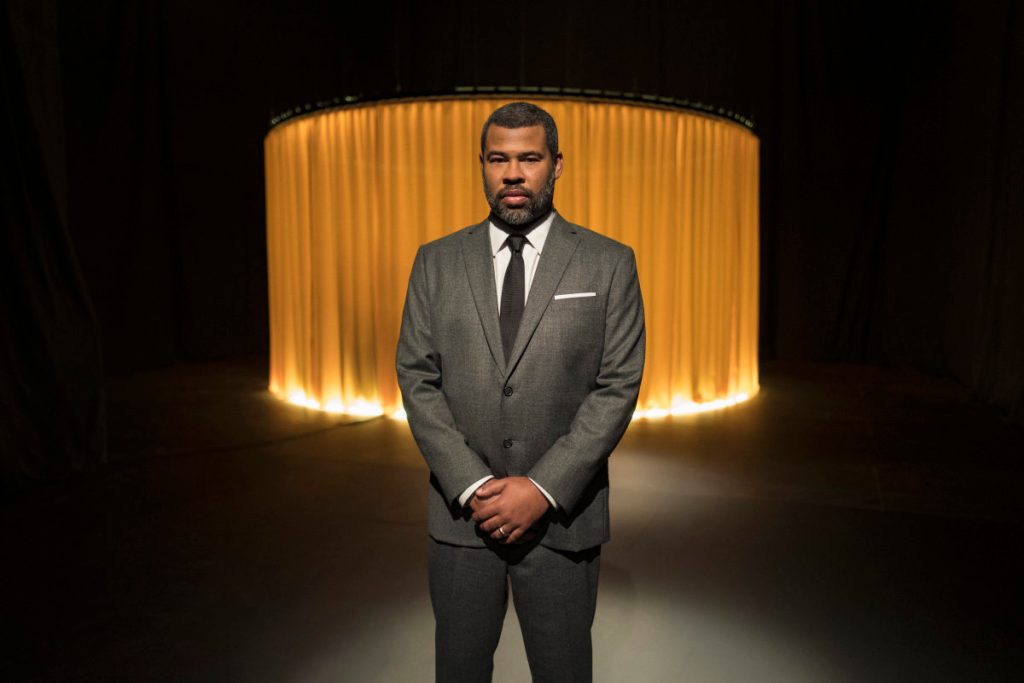

The new Twilight Zone shows us how Hollywood has turned parabolic storytelling into a witless classroom, where the message overwhelms the medium. What happens when Hollywood’s writing room and top-floor executive conference rooms become ideologically homogenous? Enter Jordan Peele in a tailored suit, monotone, introducing us to episode one, ’The Comedian.’ An Indian-American comedian named Samir Wassan is frustrated that his socially aware comedy isn’t getting any laughs, so he makes a deal with a vaping devil, who gives him the same comedic powers of a morbidly obese insult-comic who’s killing it every night (while dodging a vehicular manslaughter charge), presumably, because of his white privilege. The devil — played by Tracy Morgan — gives the comedian the ability to murder his audience by simply naming them in his act. He wins the laughter that was denied to him when he was doing the right thing: when he was being a good role model for his nephew; when he was using his platform to advance the discourse on gun safety. ‘Your act is just you being superior to other people, taking them down,’ his wife protests in the final scene, which seems to suggest that Samir’s unfunny moralistic comedy was somehow, more righteous? Then again, most people are simply confused by the vague parable of ‘The Comedian.’

Serling had no intention of using The Twilight Zone to grind his axe or wag his finger. He had a point of view, and furiously protested prejudice. But his parables were usually so carefully written that the writer’s hand seemed almost weightless. The Twilight Zone was as much a history lesson as contemporary social commentary. There were episodes based in the Civil War, the Old West, the Roaring Twenties, baseball, World War One, the 1960s, and the forgotten heartland of America.

Peele instead focuses on the now, or where we might be headed if we don’t comply. The reboot is more limited in scope and far more informed by Hollywood’s prejudice for the middle of the country. His Twilight Zone, thus far, has followed in the footstep of Black Mirror, towards a near future where the great perils facing mankind are technology and white privilege. The moral lessons in the new Twilight Zone lack Serling’s ability to win over every American. Serling’s parables were straightforward and non-coercive. He wasn’t using fear to indoctrinate, or exact revenge. He offered humanist commentaries on prejudice, alienation, war, greed, death, superficiality, and isolation. All Americans could relate to this, regardless of class or politics. But Peele’s Twilight Zone wanders into crude and distracting talk-backs. The architecture of each script collapses under the weight of the writer’s clenched fist, holding firmly onto the agenda.

In the third episode, ‘Replay,’ a black mother has a camcorder that allows her to replay the experience of watching her son gunned-down by a bigoted cop as she attempts to drive him to his first day of college. The cop is a grim reaper on a mission to collect another soul. The camcorder is her only weapon against the pie-eating and overweight Middle American police officer.

It’s the set-up of a Seventies exploitation film, not a thoughtful parable like the one it’s paying tribute to, ‘A Most Unusual Camera’. Its cause may be noble, but because ‘Replay’ beats you to death with agenda, it feels like an opinion piece, not a parable. For these reasons, Peele’s revived series will be remembered only as a recycled souvenir of the Trump era, and Hollywood’s unimaginative ‘resistance’ to it.