Remember hygge, the Danish art of warding off existential horror by suffocating your fear and trembling beneath a soft blanket? The cult of coziness is a Scandinavian speciality. You too would insist on marshmallows in your hot chocolate if there was a howling blizzard outside your window — in May. You too would feel like making the best of living alone with a cat and a set of matching sofa pillows if you had no choice but to live alone like Agnetha from ABBA in ‘The Winner Takes It All’.

It was a Dane, Søren Kierkegaard, who wrote Fear and Trembling. This is not a novel set in a Danish dinner party, but a reflection on patriarchal authority and the uses of religious despair. No amount of hygge could have consoled Kierkegaard, just as no blanket was soft enough to cheer up European philosophy’s other master of disaster, Schopenhauer. Hell hath no fury like a Lutheran who no longer wants to believe in hell. The hallucinatory taste of brimstone lingers on the tongue. You could, if you really wanted to punish yourself, assemble a list of key modern figures who, like Kierkegaard and Schopenhauer, were raised as Lutherans, lost their faith, and never got over it: Strindberg, Nietzsche, Hermann Hesse, Jung — all the top comedians.

A Fortunate Man, Bille August’s latest on Netflix, is a three-hour adaptation of the ever-popular eight-volume Danish novel Lykke-Per. Its author, as everyone knows, was the world-famous Henrik Pontoppidan, who — and who has ever forgotten it? — received half a Nobel Prize in 1917, the other half going, as even the simplest American child knows, to Pontoppidan’s contemporary, the poet Karl Adolph Gjellerup, who liked nothing more than curling up on a dark winter’s night with a blanket, a mug of hot chocolate, and a loaded pistol.

Lykke-Per, obviously, means both ‘Lucky Per’ and ‘Happy Per’. Pontoppidan is making the Lutheran case that you can either be ‘lucky’ by sinning your way to material success in this fallen world, or you can be ‘happy’ by doing what your fathers heavenly and terrestrial tell you to do, and not forgetting to fall regularly to your knees and pray that when the time comes, Satan will be gentle with the toasting fork.

Per is the son of a country preacher in Jutland, a windswept and watery region of Denmark. He is a visionary, which by local standards makes him a heathen sinner. His wicked vision is to modernize Jutland by building a network of canals and a seaport, so he decides to study engineering in Copenhagen. When he leaves home, his father’s curses him for his arrogance, and in particular for refusing to accept his grandfather’s watch and chain. Per is already in hygge deficit, and things don’t get much more cozy in Copenhagen. He rents a freezing attic, works his way through college by washing up in a restaurant kitchen, and feeds himself on slops from the dirty plates.

Per tries to sell his plan to modernize the Danish economy to the government’s chief engineer, but the engineer is pompous and dismissive, causing Per to erupt in anger. But a chance meeting leads to an introduction to the Salomons, a Jewish business dynasty. Per, being an enterprising sort, orders a new suit that he can’t pay for, falls in love with the younger of the two Salomon sisters and then, when he learns that the older one, Jakoba, will inherit her father’s money, switches his attentions to her. Jakoba’s father accepts Per into the family, backs his business plan, and organizes a syndicate of investors. But the plan cannot proceed without support from the government’s chief engineer. All that is required is for Per to issue a public apology for his earlier outburst. And Per, being a wicked and arrogant man who has yet to pay for his suit, refuses.

The title and plot of A Fortunate Man reminded me of Kingsley Amis’s Lucky Jim. In Amis’s novel, the arrogant young academic dates his professor’s daughter, runs afoul of local customs — insufficient respect for folk music rather than Lutheranism — and delivers an unapologetically bad performance at the lecture which might be his big break. But Jim Dixon breaks free from the patriarchy. Per lacks the inner resources to escape. His mother dies, leaving him the patriarchal watch and chain as her only legacy, and forcing him to return to Jutland for the funeral. Distraught, he falls to his knees before his father’s successor at the local church, falls in love with the preacher’s daughter, and breaks of his engagement to Jakoba, as Søren Kierkegaard broke his engagement to Regine Olsen.

‘I’ve felt alienated all my life,’ Per says. It gets worse. Per develops cancer, and retreats to a cabin by the sea, consoled by his platonic reunion with Jakoba. Here, he finds the hygge that passeth all understanding, rustic, morbid and lonely.

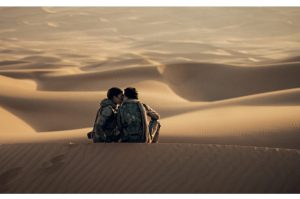

A Fortunate Man is beautiful to look at, all icy blue skies and Hammarskjöld interiors. There’s not a weak performer among the cast. The pacing of the script is excellent; you never know when and how Per’s life is about to get worse, only that he is the master of his own fate, and that is his problem.

‘When he struggles along the right path,’ Kierkegaard quipped, ‘rejoicing in having overcome temptation’s power, there may come at almost the same time, right on the heels of perfect victory, an apparently insignificant external circumstance which pushes him down, like Sisyphus, from the height of the crag.’

Dominic Green is Life & Arts Editor of Spectator USA.