In the shadows of the British Enlightenment lurked the Caribbean sugar plantations. Masters routinely raped their slaves, punished minor wrongdoings by forcing one to shit in another’s mouth and even burnt some at the stake while growing the cane destined to sweeten the tea tables of London salons, Oxbridge dons or Hampshire parsons.

It’s from this civilized viewpoint, top-down and half the world away, that we still tell the story of the abolition movement, William Wilberforce and the House of Commons, the great breakers of chains. But slaves were perfectly capable of fighting for their own freedoms, as the Harvard historian Vincent Brown shows in Tacky’s Revolt, his careful reconstruction of an understudied footnote in Jamaican history. For 18 long months between 1760 and 1761, slaves turned the whip on their masters. At 1,000-strong, it was the largest rebellion in the British Empire that century.

Jamaica was the apple of Britannia’s eye, lucrative through its booming sugar trade and strategically placed for raids on rival empires. But the British turned this tropical paradise into a hellscape. ‘In countries where slavery is established,’ Montesquieu correctly assessed, ‘the leading principle on which the government is supported is fear.’ Fear of violence kept Africans from insurrection, while fear of insurrection kept whites violent. Children thrashed fences in playful imitation of the blood-flecked floggings they witnessed every day in the fields. Skulls grinned atop posts across the landscape, warnings to would-be runaways.

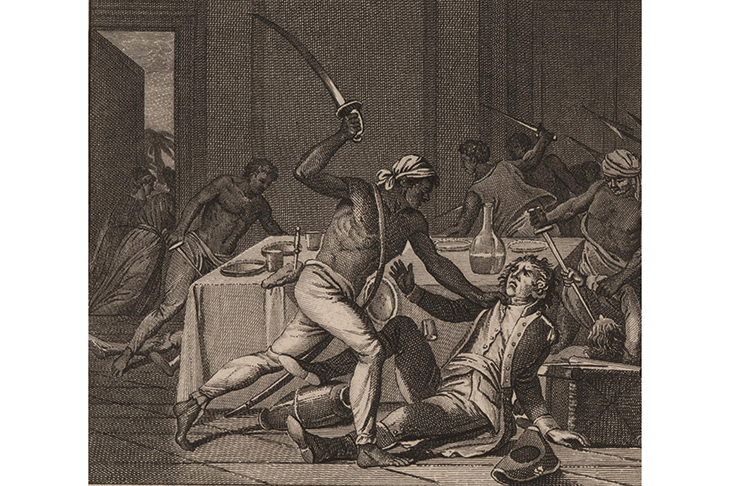

But suddenly fear wasn’t enough. A little after midnight on April 8, 1760, 100 slaves forced their way into the unguarded Fort Haldane on the north-east coast, seizing guns, powder and ammunition. They marauded through the countryside, raiding manors, murdering hated overseers and setting crops alight. Contrary to what whites christened it, it was not in fact Tacky’s revolt. The eponymous headman was one of several ringleaders scattered across the island, all rumored to be deported African officers, royalty and aristocrats. Little is known about any of them beyond the swirling vagaries of white hearsay. Brown sees the uprisings as co-ordinated, carefully timed for the Navy’s departure to guard the sugar convoy back to Britain. For the next year conflicts between militia and rebels resembled modern guerrilla warfare. Small rebel columns would suddenly converge on a target and swiftly disappear. Minor skirmishes, ambushes and booby traps replaced pitched field battles, soldiers burning crops to starve rebels out, innocents confused with insurgents.

Far from the usual chaos of a ‘revolt’, Brown sees this as a slick military operation, employing the tactics of African warfare. Many recent slave arrivals were ‘Coromantee’, people from the Gold Coast renowned for discipline and hard work. Bred in the crucible of West Africa’s warring kingdoms, they were rapidly militarized once Europeans began trading guns for captives on the coast. When trade boomed in the first half of the 18th century, men and women were sold for the price of a bottle of brandy. The slow tipping of Africa into militarism sowed the seeds of future insurrection. Unwittingly, slavers were now shipping thousands of hardened soldiers to the Americas. Of all European colonies, Jamaica received the highest percentage of Coromantees.

What did they hope to achieve? The rebels left no reliable records, information coming from tortured confessions and the speculations of paranoid whites. But their motive was obvious enough. Decades earlier, one captured escapee angrily told a trader that he was a ‘great Rogue to buy them, in order to carry them away from their own Country; and that they were resolved to regain their Liberty if possible’. But even if they did gain their freedom, where would they go and what would they do? A ramshackle town was built high in the mountains, rebels lugging up heavy chests full of frilled shirts, cravats, petticoats and stockings. Perhaps adorning themselves in the garb of their ex-masters was a step to rebuilding self-worth.

Loyalties were more complex than black vs white. Some slaves resented the rebels for jeopardizing what little they had, informing on plots and hunting down insurgents. Then there were the Maroons, the offspring of decades of lone runaway slaves who had fled to the mountains. In the 1750s they fought for a treaty to recognize their freedom and land claims. They were ‘our friend Negroes’, honor-bound to fight alongside whites, a bizarre hybrid of European and African. One captain swaggered about with silver rings encrusting his ears, fingers and toes and sported a gold-laced hat and a locket of George II, which bounced proudly on a chest swathed in an embroidered waistcoat. The revolt was a chance to earn the white man’s trust. Tacky was eventually killed by a Maroon marksman.

The main rebel momentum ended in October 1761 as a result of starvation, British attrition and mysterious internal divisions. In a mix of defiance and despair, some chose suicide to re-enslavement. Men, women and children were found hanging from trees by the dozens, ‘their bodies twisting in the driving rain’.

The rebellion sent ripples across the Atlantic world. Some started advocating the abolition of slavery for the Empire’s security rather than from any Christian qualms. Brown argues that it spurred parliament to centralize government and raise colonial taxes, sparking a more successful revolt in Boston in 1773. But, after Jamaica, American claims of living under ‘an absolute tyranny’ sounded rather hollow.

Resistance smoldered on in Jamaica itself. More revolts broke out during the late 1760s and 1770s. Rebel slaves were deported across the Americas, including Haiti, where they may have spread the news that whites were not invulnerable. An architect of the Haitian Revolution, a slave and oracle named ‘Boukman’, is supposed to have come from Jamaica. In 1807, the year of the Slave Trade Act, one plantation owner overheard workers telling new arrivals the story of the uprising — events that had occurred 40 years before they were born. Perhaps Tacky’s Revolt showed the slaves of the Caribbean that they could break their own chains.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.