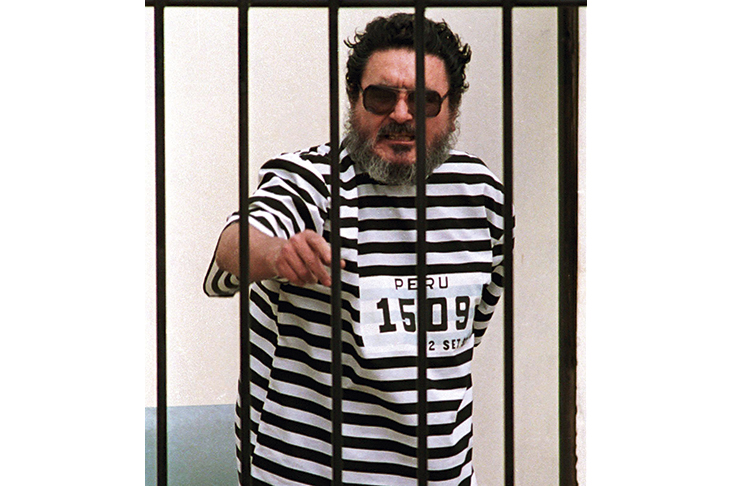

Few Peruvians today are interested in ‘the Shining Path years’, which left no traces besides 70,000 mutilated bodies and a wrecked country. Modern Lima, by and large, is a thriving city of five-star restaurants, shopping malls and newish Toyotas. Yet between 1980 and 1992 it was a vile and violent place, under siege from a revolutionary movement that modeled itself on Mao, Pol Pot and Enver Hoxha, and which venerated its leader as these men’s planetary heir. If anything, Sendero Luminoso was a precursor of Isis, with its child-suicide bombs, its rigid code of secrecy and its cultish devotion to a short, bearded, chubby figurehead who believed that ‘violence is a universal law’.

About this ‘maximum leader’ — the Fourth Sword of Marxism-Leninism-Maoism — tantalizingly little was known. Private, dogmatic, self-serious to a clownish degree, Abimael Guzmán was the illegitimate son of a womanizing sugar-plantation manager. He had written his dissertation on Kant, and was a philosophy professor at San Cristóbal University in the remote Andean city of Ayacucho when, in 1980, he fell off the radar. Among the few biographical scraps attached to him were that he disliked the music of Porgy and Bess and drank mineral water on his honeymoon.

Living in Lima at that time, and intrigued by his ongoing absence from the record, I wrote an investigative report about Guzmán for Granta, and then a novel, published in 1989, which proved a vindication of the fictional process, illustrating that if the available facts are absorbed, perhaps anything you anticipate is likely to be close to the truth. I gave him psoriasis, plus a taste for American cigarettes and the music of Frank Sinatra, and when, three years later, on September 12 1992, he was captured above a ballet studio in Lima, just as his movement seemed poised to take over the capital, I was more than astonished to learn that he had been tracked down precisely because of the Winston Light cigarette butts found in the studio’s rubbish bags, along with pills for his psoriasis. Motivated to write a second novel about Guzmán, I discovered from the police general who arrested him that he and his late wife Augusta de la Torre liked to sing Frank Sinatra’s ‘My Way’, sometimes in the Spanish rendition of the Argentine crooner Vicente Fernández.

It has taken a further 25 years for its two Peruvian authors to compile this history of the Shining Path. For a long time, the leaders chose not to speak, and other witnesses were too afraid to do so. Upwards of 50 journalists were targeted among the ‘selective annihilations’: ‘We kill journalists. Journalists takes sides,’ Guzmán’s mentor at San Cristóbal, the ethnologist Efraín Morote Best, told me back in 1987.

Journalists weren’t the only casualties. The Shining Path murdered language as well. Guzmán chose ‘Gonzalo’ as his nom de guerre, after the old German word for ‘warring’, but his ‘invincible Gonzalo thought’ never rose above tedious and abstract attacks on capitalism that were gobbledygook to the illiterate mountain peasants he insisted on liberating (‘Let Strategic Equilibrium Shake the Country!’). Either that, or it anointed itself into sentimental anthems such as: ‘The blood of the people has a rich perfume, it smells like jasmine, violets, geraniums and daisies.’

Some of this language has infected the narrative of Orin Starn and Miguel La Serna, a Duke University-based anthropologist and a University of North Carolina-based historian, which despite their top-tier American credentials, should be less tinny than it is. Their repeated claim that Mario Vargas Llosa ‘churned out’ his novels betrays an ignorance of the writing process that is reflected in their casual rat-a-tat-tat deployment of clichés, or in tone-deaf phrases such as ‘the ethno-musicologally-minded Osman Morote [Efraín’s Sendero son]’.

Style aside, there are surprising omissions for a history that has taken ‘more than five decades between us’ to complete. The significance of the early Senderista, Edith Lagos, is galloped over. Also, the way that Sendero manipulated Andean myths, such as that of the evil bogeyman Pishtaco, for their ends, and the fact that several of their leaders had trained for the priesthood. Nowhere is mention made of the British army officer Major-General Richard Clutterbuck, a pioneer in the study of political violence, and his game-changing visit to Lima to give police chiefs such as General Antonio Ketin Vidal the benefit of his counter-insurgency experience in Malaya. He urged Vidal not to execute suspects secretly, as the military had been doing in Ayacucho, but to shadow them like Sherlock Holmes. Nor, having interviewed Vidal twice, am I persuaded by the authors’ quite controversial claim that he was merely a bit-player in Guzmán’s capture.

More valuable are the sections on Guzmán’s first wife, Augusta, or Comrade Norah. Without her call to action, Guzmán would probably have remained a reserved and provincial theoretician. Augusta, the ‘bright-eyed’ daughter of a local plantation owner, hanged herself in 1988, for reasons still unclear — although her mother in 2016 declared that she was murdered by another prominent Senderista, Elena Iparaguirre, who, as Comrade Miriam, eventually became Guzmán’s second wife and the movement’s No 2.

A ‘ghost’ who was more representative of Peru’s white-skinned landowning class than of Quechua-speaking indians, Guzmán did not set foot in the Andes for a decade. He hid out in middle-class safehouses in cosmopolitan Lima, such as the upstairs apartment of the ballerina Maritza Garrido Lecca (‘a slender coal-eyed beauty’). Little wonder that her boyfriend reacted: ‘When my friends and I were stoned, we wondered if Chairman Gonzalo was just a hologram.’

Unlike Pablo Escobar, Butch Cassidy or Che Guevara, Guzmán was captured with ‘not a drop of blood’ spilled. This was thanks to Vidal, who discovered ‘the Teacher of Teachers, the Eagle of the Andes’ sitting in a leather chair watching the boxing on Channel 13. Politely, Vidal said: ‘You must know that in life you win some and you lose some. And this time, sir, you’ve lost.’ Guzmán stood, and pointed at his spotty forehead: ‘You can kill a man, but you can never kill this.’ He was talking about ‘Gonzalo thought’.

Since 1992, he has been allowed no visitors to his naval prison cell, except once a year his wife, and a weekly visit from his lawyer, Alfredo Crespo. In all that time, Guzmán has never been interviewed. Yet on my last visit to Lima, Crespo did offer to put to him one question from me. I had waited more than 25 years for this, my first direct communication with the godhead. What could I ask?

Crespo had told me that Guzmán read Shakespeare every night. On May 17 1980, he had announced his revolution with a quotation from The Tempest, before he disappeared underground: ‘No tongue; all eyes; be silent.’ I told Crespo what I wanted to know. That evening he met with Guzmán. Next morning, we had breakfast. ‘I asked Dr Abimael your question — which is the play of Shakespeare he likes best? Richard III, he says. Followed by Macbeth.’

It rang true. Both plays are about betrayal, usurpation and the hollowness of power.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.