Being in the south of France obviously gave Vincent an enormous joy, which visibly comes out in the paintings. That’s what people feel when they look at them. They are so incredibly direct. I remember in some of his letters Vincent saying that he was aware he saw more clearly than other people. It was an intense vision… [H]e must have been doing some very concentrated looking. My God! After working for a long time, I get very tired eyes. I just have to close them…

Photographs of those fields around Arles that Van Gogh painted wouldn’t interest us much. It’s a rather boring, flat landscape. Vincent makes us see a great deal more than the camera could. With a lot of his work, most people who actually saw the subject would think it was incredibly uninteresting. If you’d locked Van Gogh in the dullest motel room in America for a week, with some paints and canvases, he’d have come out with astonishing paintings and drawings of a rundown bathroom or a frayed carton. Somehow he’d be able to make something of it. I think Van Gogh could draw anything and make it enthralling…

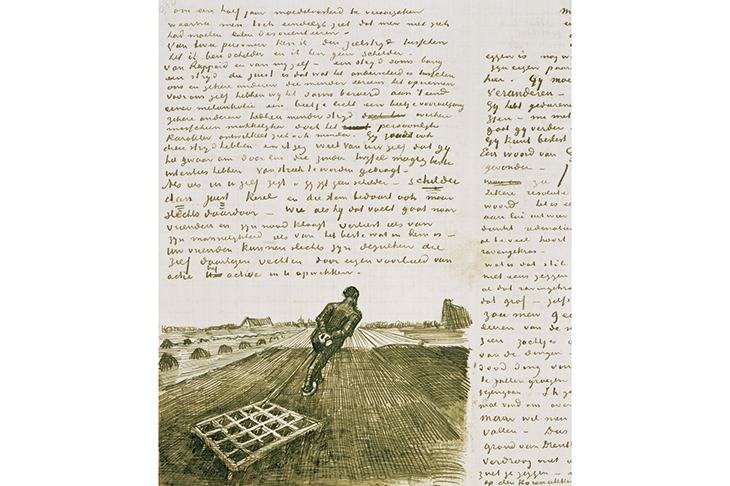

I love the little sketches in his letters, which seem like drawings of drawings. They are condensed versions of the big pictures he was painting at the time, so that Theo and the other people he was writing to could understand what he was doing. These days he’d be sending them on his iPhone. When you look at them, they contain everything. It’s all there. He certainly didn’t do anything by halves.

Those early drawings of the peasants are incredibly good, technically. You really feel volume, get a sense of the body and the texture of the fabric of the clothes they are wearing — and yet they transcend that, because the empathy is so strong. But technically they are as good as any drawing you’ll ever see. Rembrandt could do that too. You feel whether the clothes his figures are wearing are ragged or a refined cloth, even if he has just used six lines.

With a truly great draughtsman, there is no formula. Each image is something new … You never get a repeat of a face in Rembrandt or Van Gogh; there’s always something of the individual character. I love looking through the Benesch catalogues of Rembrandt’s drawings; I keep one set in LA and another one in Bridlington. They are endlessly good for entertainment, better than films. Looking at them is an incredible pleasure.

With Rembrandt you never get a generic face, the eyes are always amazing. In a slight elongation of mark — just a little line and a blob — a set of eyes becomes old and tired. You can tell just where they are looking. Every face is different, just as it is in reality. He was wonderful at old men. There was incredible empathy. To me, the drawings are the greatest Rembrandt; the paintings are wonderful, but these are unique.

That’s what we’d see in real life if we were looking. We’d notice straight away the old hands, the sad face. That’s why Rembrandt’s so human. Anybody who’s ever drawn very quickly sees how wonderful Rembrandt’s drawings are; the economy of means takes your breath away. The hands, for example, can be quite crude, but in another way you totally get them. He can draw old hands in a couple of lines. Often you can tell that a certain line must have been done very fast. You can see the speed.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.