Norman Stone has already written, with a brilliant blend of humor, understanding and skepticism, histories of the Eastern Front, Turkey, Europe between 1878 and 1919, both world wars and the Cold War. A history of Hungary is his latest book. He has one qualification increasingly rare in England. As polyglot as an educated archduke, he knows Hungarian in addition to German, French, Russian and Turkish. Moreover, he has been visiting Hungary for more than 50 years, since he first went as a student in the dark days of 1962. He has returned many times — his Hungarian improved in a communist prison and he reported the fall of the communist regime in Budapest in October 1989 — and now lives there part of the time.

As befits the history of a country situated where three empires (Austrian, Russian, Ottoman) met, there is never a dull page. Until recently, Hungary combined a passionate sense of national identity with an unusual degree of diversity. No admirer of the Catholic church, Stone stresses the importance of the Calvinist and Lutheran minorities in Hungary’s development. In the 17th century they helped make the principality of Transylvania, in what was then the eastern section of the kingdom of Hungary, unusually prosperous. Protestant Hungarians, as well as some Catholics, took refuge in the Ottoman empire from rule by Germanizing, Catholic Austria. At the Ottoman siege of Vienna in 1683, Hungarians fought on both sides. A Hungarian national hero, Ferenc II Rakoczi, Prince of Transylvania, now the face on the 500 forint banknote, died in exile outside Constantinople.

As in other countries, in Hungary nationality was often a career choice rather than an inherited identity. Stone points out that, after Hungary was repopulated with the help of Germans and Serbs in the 18th century, the population was ‘not even half Hungarian’. English and Scottish engineers, Armenian and Greek traders also settled there. In the late 19th century perhaps a quarter of the population of Budapest was Jewish. Stone points out that the capital owed them much of its prosperity and cultural glory, its ‘hothouse schools’, dazzling writers and Nobel prize-winners.

Hungary inspired loyalty. Franz Liszt, who felt Hungarian and composed Hungarian-style music, was born into a family of German origin. The hero of the 1848–9 revolution against Austrian rule, Lajos Kossuth, had Slovak blood. The film director Alexander Korda, like the writers György Lukacs and Arthur Koestler, were proud of their Hungarian roots.

Shared sovereignties were once as common as single states, as is suggested by the long lists of titles after European sovereigns’ names in official documents. Hungary’s golden age occurred after the compromise in 1867 with the multinational Austrian empire, which created the dual monarchy Austria–Hungary. Thereafter, while keeping a separate government and parliament, Hungary shared with Austria a dynasty, an army, a foreign policy and a common market, as well as, fatally, common responsibility for the toxic province of Bosnia–Herzegovina.

The franchise was low, giving only 6 percent of the male population the vote. Some called Hungary ‘an aristocratic racket’. The architect of the 1867 compromise with the Empress Elizabeth was Count Gyulay Andrassy, who 20 years earlier had fought the Austrian army and been hanged in effigy. Slovaks, Romanians and other minorities, however, resented Hungarian hegemony.

Catastrophically, as Kossuth had warned, Hungary was pulled into a ‘German vortex’ by Austria’s alliance with Germany. Moreover, some Hungarian leaders wanted a confrontation with Serbia, and made the familiar mistake of overestimating the current superpower. ‘Germany is invincible,’ sighed the prime minister, Count Stephen Tisza, as, against his better instincts, he voted for war in 1914. Another count, Albert Apponyi, who had closed hundreds of Romanian schools, welcomed war with the words: ‘At last.’

War led to defeat and revolution. Incredibly, despite Hungary’s long experience of Habsburg oppression, after 1918 many nobles remained monarchists. Archduke Joseph of the Hungarian Palatine branch of the dynasty, a respected general, might have remained regent for longer than a month in 1919 had the victorious Allies not insisted on his removal. The next regent, Admiral Horthy, had the former King Karoly IV (as the Emperor Charles I of Austria was known in Hungary) expelled after two attempts to recover the throne in 1921, also partly for fear of the reaction of Britain, France and Hungary’s neighbors. Thereafter, Hungary remained a kingdom without a king, ruled by Horthy, an admiral without a navy.

Stone writes: ‘In a vintage crop of stupid treaties, that of Trianon [between the Allies and Hungary] signed on 4 June 1920 was the worst.’ Against the principles of self-determination proclaimed by the Allies, thousands of Hungarians, even those contiguous to the new rump state, were placed under foreign rule. The end of Austria-Hungary meant the end of a shared currency and markets, and of what Stone calls ‘ancient accommodations and compromises’. Hungary’s decision in 1941 to enter the war on the side of Germany, which had helped it recover lost territories, was followed by a descent into nightmare: the murder of half the country’s Jews, the siege and part destruction of Budapest, the expulsion of Hungarians of German origin, the flight of many others (for example George Soros and the father of Nicolas Sarkozy); finally the imposition of a Marxist government with the help of the Red Army.

Stone makes even his pages on the Marxist years 1948–1989, and the brutal reaction to the uprising of 1956, readable. This dark age has also been described, with fascinating details from secret police archives, by Michael O’Sullivan in his remarkable Patrick Leigh Fermor: Noble Encounters between Budapest and Transylvania (Budapest 2018): police raids, disappearances, forced labour, the knock on the door. By the end, however, Hungary was evolving towards a semi-market economy.

Stone’s book shows a profound knowledge of Hungary and will become indispensable for travelers. It may, however, inspire even in ardent nationalists distrust of the nation state, and what Stone calls ‘patriotic clamor’. As he shows, the state, rather than protecting Hungarians, often led them to defeat or drove them to emigration. Even in 1867–1914, many Hungarians preferred to live in other countries. Admiral Horthy called his years in Vienna as ADC to the Emperor Franz Joseph — not his years in Budapest as regent — ‘assuredly the finest of my life’. He died in exile in Estoril in 1957.

Today Hungarians are again leaving in large numbers: half a million in the last ten years according to Stone, comparable to the mass emigrations of 1944–7, 1956–7 and pre-1914. Whatever the joys of living with the same nationality in a nation state, life abroad can have greater attractions. Hungary has not lived up to the hopes of 1989.

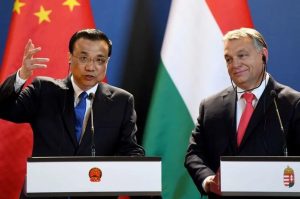

Not only is the present Prime Minister Viktor Orbán increasingly powerful, with growing control of the media; he also glories in being illiberal. Government supporters have called George Soros, who established the international Central European University in Budapest, an ‘enemy of the state’. Increasingly nationalist at home, Orbán is also showing interest in Hungarian minorities in Slovakia, Romania and Ukraine. (Shared hostility to Ukraine may explain his admiration for Putin.) The state is again leading Hungarians down a nationalist path — one which, in an age of global warming and global companies, is both dangerous and outdated.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.