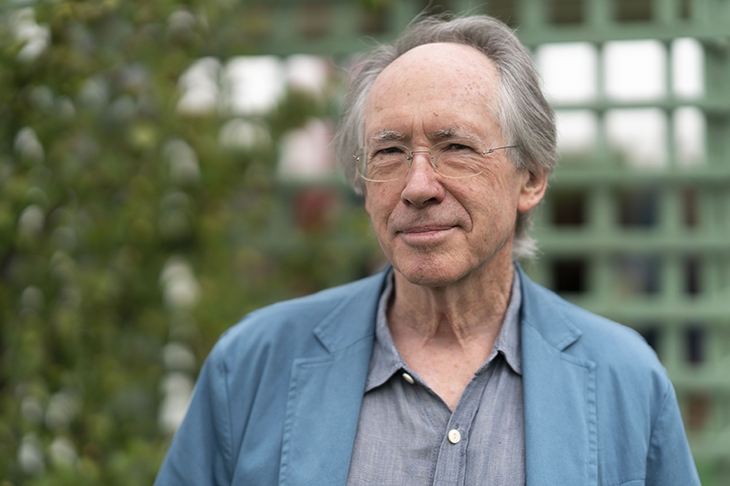

Kafka wrote a novella, The Metamorphosis, about a man who finds himself transformed into a beetle. Now Ian McEwan has written one about a beetle that is transformed into a man. He’s not the first writer to have thought of doing this, but he might be the first one who thought it was a good idea. Readers will remember that in Randall Jarrell’s classic comedy of a creative writing faculty, Pictures from an Institution, the heroine has a student called Sylvia Moomaw (‘I had remembered her name but had forgotten her’). One day, she hands in a story ‘about a bug that turns into a man…it’s influenced by Kafka’. The hero reads it (‘There was a part where the man said “Could I have ever really been a bug?”’) and is moved to a sad, brutal reflection about his pupil:

‘Once upon a time there was a princess who laid down on seven mattresses, and slept like a baby all night through, and when she woke up in the morning she said I dreamed there was something under my mattress and they looked and there was a horse.’

It’s quite an apt observation to recall, when presented with a satirical novella about Brexit. Why waste your energy on Dominic Raab when there’s a Guy Verhofstadt, a grinning goody-goody like Sabine Weyand, a Juncker staggering with post prandial sciatica, to be skewered? This cabinet goes to Bayreuth, writes civilized books about history and refers to classical civilization in passing. Are the satirist’s best endeavors to be spent ridiculing them as insect-brains? Or might we recommend a glance at some occupants of the benches opposite?

One day a cockroach wakes up to find that he has been transformed into a man. His name is Jim Sams, and he is the prime minister. Quite quickly he finds himself chairing a cabinet meeting — for the convenience of the satire, this one is apparently entirely white and male, though a single female minister appears later. His government is in the process of introducing an entirely new theoretical economic system, called Reversalism. In it, individuals will be paid for taking goods away from retail outlets, and will have to pay to work as employees. Britain is alone in the world, apart from the wavering and uncertain support of a ludicrous US president, addicted to Twitter. Shenanigans ensue.

Where to begin? Kafka’s fable works so beautifully because there is a single impossible event, and then a man’s mind is within a giant insect. We all know that feeling of helpless entrapment from experiences of illness. The impossibilities of McEwan’s situation don’t mean anything to us, and just keep coming. How are we to know what the insect mind thinks about? How does it know how to move or speak? How does it understand the complex political situation? We are quickly lost in a quagmire of unconvincing explanations. Wisely, McEwan soon drops the cockroach business and we are just in a satirical situation about an impossible economic fantasy, a little like Swift’s Laputans. Better not to have started it at all. For many of us, it will never be at all OK to describe democratically elected politicians as ‘cockroaches’. It was the word by which the génocidaires in Rwanda called their adherents to action.

McEwan, at his best, engages with literary forms, even conventional genres, filling them with warm, humane detail: the spy thriller in The Innocent, the woman’s domestic novel in Atonement, the dystopian alternate-world SF fantasy in this year’s masterly Machines Like Us. Like Kingsley Amis in his middle period of ghost stories and detective fictions, he investigates the genre conventions with gusto, and challenges them with real feeling.

It was a mistake to engage with The Metamorphosis, however, because Kafka’s engine just can’t be run in reverse. But even without that, McEwan doesn’t seem to be quite up to speed on political minutiae. When so much of the detail, from parliamentary pairing arrangements to the conventional seating in cabinet, is awry, belief starts to fail. And if the novelist is asking his reader to believe one huge impossible thing, it’s reckless to pile minor implausibilities on top.

I really hoped this was going to work. It’s vital that novelists are invested in current political realities; and the turmoil of feeling, of identity, of brutal terror that Brexit is churning up needs a report on the ground. McEwan has done this powerfully in the past — the shakiness of the Blairite mood in Saturday most memorably — and I’m sure he’ll do it properly in time, without cockroaches.

This, alas, seems like a product of our communal confusion, rage, uncertainty and posturing, and not a depiction of it.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.