‘And this is good old Boston/, The home of the bean and the cod,’ John Collins Bossidy quipped in 1910, ‘Where the Lowells talk to the Cabots/, And the Cabots talk only to God.’ Also home, in 1968, to Mel Lyman, a folk musician turned LSD guru who believed he was God, and to Van Morrison.

The music business abounds with stories about Morrison being grumpy. In my experience, he’s perfectly reasonable. You’d be grumpy if your job obliged you to consort with thieves, liars and drummers who can’t keep time. You’d be especially irritated by people asking how you wrote Astral Weeks. Sensibly, Morrison explains that Astral Weeks was written by a different person living, as its title song says, ‘In another time/ In another place.’

That time was 1968, the place Cambridge, Boston’s university town. The circumstances were that Morrison and his girlfriend Janet Planet had decamped from New York following contractual difficulties involving the breaking of an acoustic guitar over Morrison’s head and the peppering of his hotel room door with bullets. In December 1967, Morrison’s producer, the Mob-friendly Bert Berns, had died of a heart attack. Morrison’s contract passed to Carmine ‘Wassel’ DeNoia, an associate of the Genovese crime family.

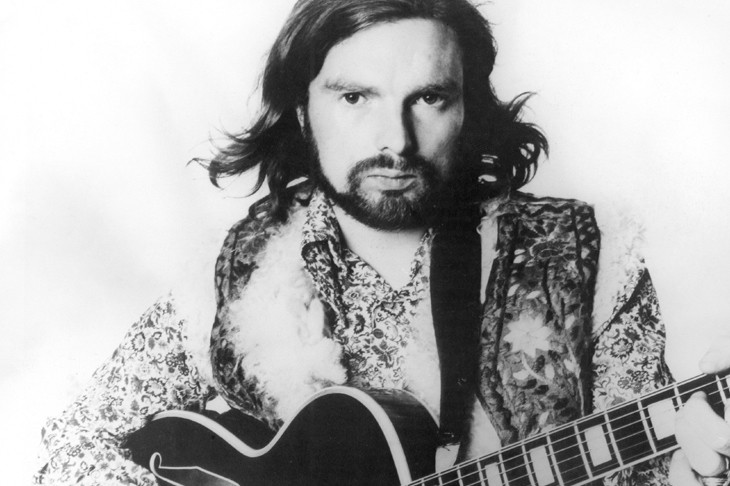

Morrison had split from Them and scored a solo hit with ‘Brown Eyed Girl,’ but he had visa troubles as well as business problems. The record labels were chasing psychedelic rock — heavy metal was slouching towards Donington — but Morrison was writing jazzy acoustic songs: ‘I’m nothing but a stranger in this world/Got a home on high.’

Cambridge is now a placid university town and hi-tech hub. In 1968, the whole of Boston seems to have been ankle-deep in LSD. The ‘secret history’ exhumed by Ryan H. Walsh is a forgotten freak scene. Researching this book, Walsh found himself inhabiting ‘an upside-down, hallucinogenic version of the metropolis’ he knows. Beacon Street, once a Jamesian parade of redbrick townhouses and now expensively dull, was a student ghetto. Roxbury, now a gentrified inner suburb, was so decayed that Mel Lyman’s acid-addled followers were able to buy up a whole street.

Lyman locked troublemakers in the basement and reprogrammed them with ‘guided’ LSD trips, but he never went the full Charles Manson. There was no killing spree, only a free sheet called Avatar and a music venue called the Boston Tea Party. The Velvet Underground became regulars.

In Cambridge, Morrison assembled a small acoustic group and created the template for Astral Weeks; his flautist, John Payne, was related to Robert Lowell. MGM tried to capitalise on the scene by hyping a ‘Boston Sound’. Walsh, tracking down a live tape from 1968, confirms that Astral Weeks was the real Boston Sound.

The 1960s were what Gershom Scholem would have called a ‘plastic hour’ in American history. The talking-to-God weirdness crystallised in California, but the countercultural reaction had begun in Boston in the days of the Cabots and Lowells. As Henry James’s satire of the table-tapping utopianism in The Bostonians suggests, Brahminic Boston pioneered ‘self-actualisation’. The first yoga studio in America was in Cambridge; William James discusses its teacher, the Hindu nationalist Swami Vivekananda, in Varieties of Religious Experience.

The local Blavatskyites identified Vivekananda’s akasha with their ‘astral plane’. Walsh notes Morrison’s interest in the third-generation Theosophist Alice Bailey, who inspired another record that broke the Pop mould, the Velvets’ White Light /White Heat. Has the protagonist of ‘Astral Weeks’, a dreamer recollecting experience in innocence, caught a whiff of Boston occultism?

Another time, another place: the real magic happened in New York. Joe Smith, the Warners executive who had signed the Grateful Dead, heard Morrison’s demos. He sprung Morrison from his contract by handing $20,000 in cash to some Italian American music lovers in an abandoned warehouse. In three sessions in October 1968, Morrison recorded a masterpiece, using hired New York jazzers and his Cambridge flautist, John Payne.

Walsh leads the Boston band Hallelujah the Hills. He has written a splendidly half-cracked cultural history, free of theoretical frottage and vivid with psychedelic colour. Great music speaks for itself, but Walsh’s findings confirm that Morrison was just passing through, nothing but a stranger in tripped-out Cambridge. It makes sense. Astral Weeks, the vinyl image of that plastic hour, is Pop’s greatest record because it isn’t Pop at all.