Sebastian Barry, Ireland’s literary Laureate, didn’t plan on taking so long to finish On Blueberry Hill. How long? Most of the decade, he confesses. At one point he wrote to his agent and offered to pay back the advance. ‘God knows, money is tight enough already in theater without me taking it for not writing a play,’ he says.

In his defense, Barry has been rather busy, publishing no fewer than three novels (including the prize-winning Days Without End) in the time it took to finish one play. Is it that he finds novels easier to write, or does he enjoy them more? Neither, he says, insisting that, despite evidence to the contrary, he’s come to prefer writing plays to novels.

‘I’m a prose writer who grew up in the theater,’ he says. His mother, Joan O’Hara, was a stage actress who starred in one of Ireland’s longest-running soap operas. ‘As a young child I just assumed everyone’s mother was an actor,’ he says. ‘I was shocked when I went to school and found that they did other things, like minding house.’

The majority of his novels derive from family folklore. One of his two grandfathers was a staunch nationalist who hated all things English; the other served in the Royal Engineers during World War Two. ‘Both were completely Irish,’ he says, yet they trod different and seemingly irreconcilable paths. One of the fondest memories of his childhood was seeing them shake hands, he says.

The stories keep coming. There’s the great-uncle who fell foul of the IRA and ended up being murdered in Chicago (‘followed there by Michael Collins’s associates’). The Catholic great-grandfather who headed up the Dublin police during the troubled Easter Rising period. ‘The family was so ashamed of him that nobody marked his grave,’ he says. You can understand why Barry uses these stories — if he didn’t, they’d likely be pinched by somebody else.

Is there anything autobiographical in On Blueberry Hill? His mother, he says, albeit indirectly. On paper, it’s an all-male play, set in a prison cell shared by two men, Christy and P.J., who pass the time by swapping stories from their past. Many of these memories are Barry’s own, in particular Christy’s stories about his mother. ‘It gives you a wonderful sense of freedom,’ he says, to examine your own past through fictional characters.

Before playing in London, On Blueberry Hill opened twice in Dublin — once in the Origin Theatre and once in the prison in which it is set. There was no stage to speak of, just a small room and 40 inmates — not all of them enthusiastic. ‘One man said, “I’m not watching a play about homos!”’, he recalls, launching into an impression. ‘The next day he was telling his English teacher how glad he was that he stayed and watched it. That’s the greatest compliment you can receive as a playwright.’

Speaking of compliments, did becoming the Irish Laureate help Barry to make peace with his Irishness, a subject with which he’s wrestled for much of his writing career? ‘Of course in a moment like that you’re going to be seduced into feeling pure citizenry,’ he says. Yet he still bristles at being labeled an ‘Irish novelist’, insisting he doesn’t really speak the language of Irishness. Is there even an ‘Irish canon’ anyway, he asks?

‘Our writers are like the old Irish kingdoms: they don’t really talk to each other unless they’re shouting abuse. People talk about traditions in writing, but when you look at what they call Irish writing, it’s basically a bunch of mavericks doing all they can to get away from each other. Look at Samuel Beckett. Look at Synge. Look at Joyce running off to Zurich.’

He remains drawn to fellow outsiders like the historian Roy Foster, who has spent much of the past 30 years skewering the follies of Irish nationalism. Their friendship echoes that of Ian McEwan and the late Christopher Hitchens: admiration for each other’s work, and a distinctive whiff of ideological kinship. Foster, he says, has been as influential on his thinking — certainly on the question of Irishness — as Yeats. Barry’s eyes light up when he talks of him.

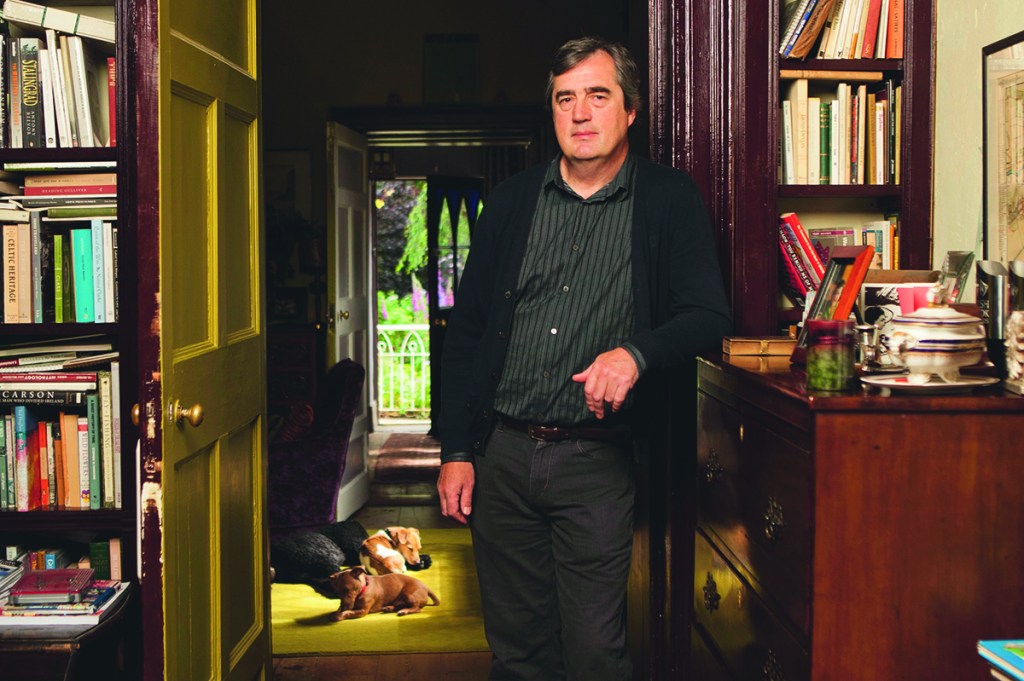

He speaks of his admiration for the actors he’s worked with on his plays — Claire Bloom, Donal McCann, Sinéad Cusack. Did he never want to act himself? His live readings, some of which can be found on YouTube, are brilliantly flamboyant, with Barry — a six-foot-something mountain of a man — unable to resist the temptation to put on bombastic accents or segue into Irish folk ditties. Are these the trappings of a frustrated thespian, or just a writer trying to enliven a book tour? The theatricality is deliberate, he admits: when you spend years watching actors, it’s hard not to pick up a trick or two.