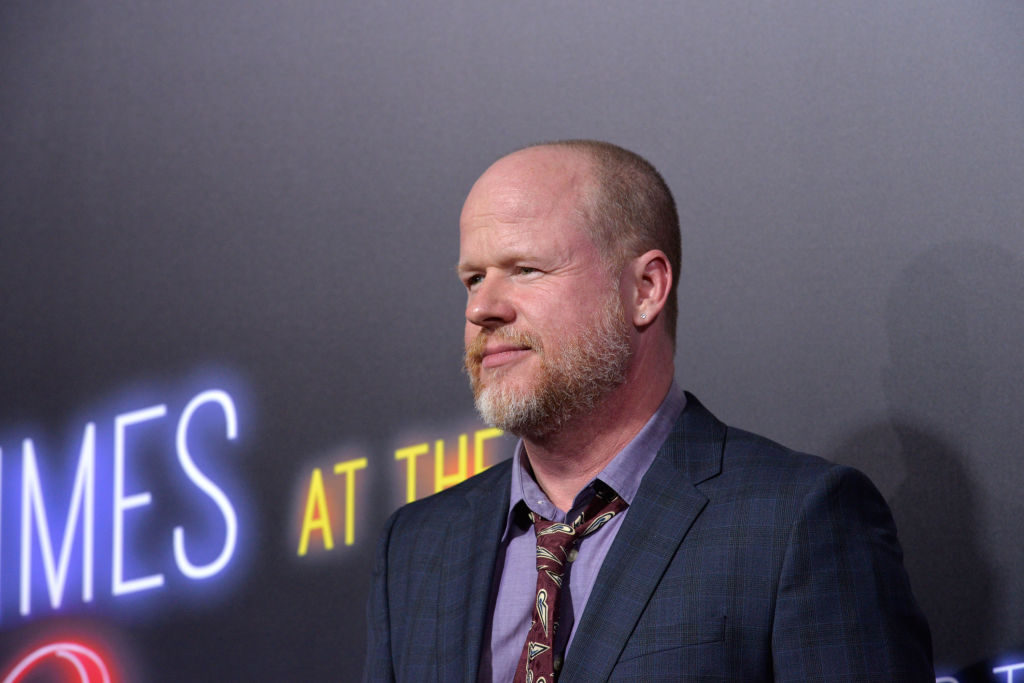

Former loved ones and associates of Joss Whedon, creator of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Angel, Firefly and The Cabin in the Woods, have formed an orderly line to charge the writer and director with cheating and abuse. At this point it is only a matter of time before his gardener comes forward to claim that his checks bounce.

Whedon’s ex-wife accused him of serial infidelity and gaslighting. Justice League star Ray Fisher accused him of ‘gross, abusive, unprofessional, and completely unacceptable’ behavior. Now, Charisma Carpenter of Buffy and Angel has accused Whedon of calling her fat when she was pregnant and mocking her religious beliefs. For good measure, actress Michelle Trachtenberg came out to insist that on the Buffy set there was a rule that Whedon could not be alone in a room with her.

To be fair to Whedon, none of these claims suggest criminal behavior. They add up to being an asshole rather than being a monster. But that is not nothing. It is especially ironic when Joss Whedon has spent years insisting that he is a ‘woke bae’, building his brand around ‘strong female characters’ and emphasizing, ‘we need equality. Kinda now.’

Whedon’s artistic preoccupations add to the irony. His shows and films are packed with brave, confident women standing up to, and surpassing, men, and clear Avengersesque divisions between good and evil. That their creator pushed women — and men — around and could be so obnoxious in pursuit of his own vision muddies this cheerful idealism.

In her accusatory 2017 essay, Kai Cole, Whedon’s ex-wife, wrote:

‘I believed, everyone believed, that he was one of the good guys, committed to fighting for women’s rights, committed to our marriage, and to the women he worked with. But I now see how he used his relationship with me as a shield, both during and after our marriage, so no one would question his relationships with other women or scrutinize his writing as anything other than feminist.’

In its way, this expressed a broader sense of betrayal. How could Whedon, of all people, not be one of the good guys?

For conservatives, and people who just hate Whedon’s work, there is an element of schadenfreude in the unraveling of his reputation. Whedon, more than anyone, contributed to the popular conception of a ‘male feminist’ as someone who self-consciously defends women in public while mistreating them in private.

Still, the left have similar archetypes: the priest or evangelical with an unwholesome private life, and the staunch defender of small government who somehow profits from the public purse. I am not just here to aim a kick at Whedon, then, or male feminists in general, but to talk about the difference between having ‘good’ opinions and being a good person.

It is tempting to assume that if someone advocates your values — say, order, prudence and tradition if you are on the right, or equality and diversity if you are on the left — they also put those values into practice in their lives. Perhaps they do. Perhaps they don’t. It is also tempting to assume that if our favorite artists create characters we love and work that makes us feel ennobled they must be lovable and noble themselves. Perhaps they are. Perhaps they aren’t.

The opinions we express in public, or the values we portray, need not cohere with our private behavior. Graham Greene’s Catholic literature, for example, coexisted with prolific womanizing and voracious brothel-hopping. Elton John famously changed the lyrics of the bearded shopaholic John Lennon’s ‘Imagine’ to, ‘Imagine six apartments, it isn’t hard to do, one is full of fur coats, another’s full of shoes.’

In some cases, people defend values they do not practice with the dishonesty of a mountebank who sells a cure he knows is fraudulent. You hope such occurrences are rare. But if people can sell a phony cancer treatment they can sell a phony worldview.

Still, people can really believe something without acting upon it. Human beings are very talented rationalizers. We can excuse our own misbehavior to ourselves. We think, for example, that an immoral act is so ubiquitous — from sexual impropriety to the wasting of resources — that our individual behavior makes no difference.

We strain our mental sinews to convince ourselves that our actions are qualitatively different from those we condemn. You bully, I banter. You are dishonest, I spare people’s feelings. You are a thief and I am taking what I deserve. More than this, though, I think we tell us ourselves that saying good things makes up for not doing good things — as if our words, in all their minimal consequentiality, have the power of absolution.

There is no link between insight and virtue. A man’s immoral behavior does not invalidate his work. Very bad people can have very good ideas and very good people can have very bad ideas. Very bad people can make very good art and very good people can make very bad art, as there is no necessary link between talent and righteousness. Benvenuto Cellini was a criminal, a killer — and a great sculptor. (I am not attempting to equate Whedon and Cellini here. Whedon is obviously not such an evil man, nor such a talented artist.)

Still, our work and our words, almost certainly do not leave as great an impression on people as our behavior. Even if we are lucky enough to have an audience, our ideas and our art do not affect people as powerfully as our deeds affect our friends and family members. We should not be so pious as to imagine that our favorite intellectuals and artists must have private lives as pure as newly fallen snow. Still, that’s no excuse not to ever try to live up to the values they espouse. If I cannot practice what I preach, after all, how can I expect anyone else to?