There is a moment in the first episode of Dolly Parton’s America when you think the sainted songstress may have made the worst mistake of her career.

‘Do you think of yourself as a feminist?’ asks host Jad Abumrad. ‘No, I do not,’ Dolly says.

There is a pause as wide as the gap between those who have four-year degrees and those who don’t.

After Dolly says she thinks feminism means hating men, Abumrad cuts to an interview with feminist, Heartland author and Dolly superfan Sarah Smarsh. They grasp for a reason why Dolly would think so non- progressively. The interview starts to feel like a wake.

‘The part of me that’s pissed off,’ Smarsh says, ‘is the part of me that got to go to college.’

Dolly Parton has all the makings and doings of a true feminist, but maybe she fears calling herself one due to the misinterpretation of feminism in her day, Smarsh ventures. Dolly sang songs for women and men, she is a powerful, hardworking woman, and she celebrates femininity: an ‘OG third-wave feminist,’ Smarsh insists enthusiastically.

Dolly can do no wrong, even in 2020. The feminists forgive her, the conservatives forgive her for voicing support for Black Lives Matter. Not all musicians get these breaks. Music is so fundamental to us that adoration forgives even vicious flaws. In Dolly’s case, the sins to be forgiven, it appears, are anti-feminism and capitalism.

For Jimi Hendrix, the defects are heroin addiction and alcoholism. Those faults are given life in The 27 Club, a podcast about rock stars who died at 27. Like Dolly Parton’s America, this podcast demonstrates that fans fit artists to their desired mold.

Host Jake Brennen narrates stories about Hendrix with no chronology or thematic order, but much superfluous darkness. He is oddly passionate about Hendrix’s less impressive moments of improvisation, like when Jimi and his Playboy bunny girlfriend got into an alcohol-fueled fight and he threw a bottle at her head. For a podcast about one of the great American musicians, Brennen rarely dives into Jimi’s music. Instead we flit randomly through girlfriends, drugs and run-ins with other rockers. In one episode, the only reference to Jimi’s lyrics is the already notorious tidbit that Jimi named ‘Purple Haze’ for his preferred brand of LSD.

Jimi’s personal life is better known than Dolly’s, and that’s too bad: his was sad and hers is inspiring. Jimi isn’t available for comment, and our morbid fascination with his addiction is eclipsing his musical genius. The podcast speculates about whether mobsters or musical rivals had a hand in him choking on his own vomit. It would be way more fun listening to Hendrix instead.

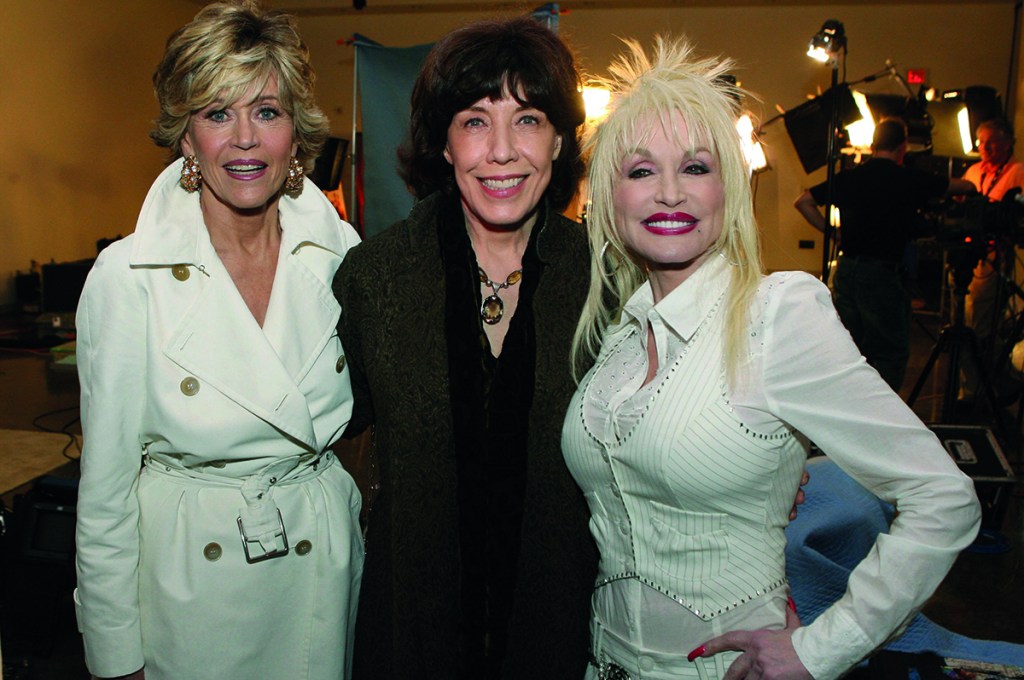

Jimi’s real flaws are celebrated as part of his tortured artist image; the myth even demands them. Dolly’s alleged flaws are explained away: her cash is forgiven by her endless charitable work, her anti-feminist stance is forgiven by recasting her as a covert feminist, or a woman of her time who’s afraid of the word. It’s hard to tell which is worse. When Dolly Parton’s America addresses ‘Dolitics’, we revisit the 2017 Emmys, when Dolly, Lily Tomlin and Jane Fonda were reunited on stage for the first time since 9 to 5 (1980). At the awards, both Tomlin and Fonda attacked President Trump by citing a line from the movie.

‘Your eyes got really wide when they said it,’ Abumrad says.

‘Well I didn’t like it,’ Dolly replies. ‘And I had already told Jane and Lily, “Look, now I’m not going into the politics of anything… I don’t do politics.”’

She knows her fans are on both sides, so she keeps her opinions to herself. ‘It’s not my place to be doing that anyway,’ she explains. ‘I’m an entertainer… I’m not up here to bash somebody else.’

The producer, Shima Oliaee, probes Dolly from the left.

‘When you’re in a room and everyone is attacking [Trump], because of your story of forgiveness, does it almost make you feel like you want to protect him?’

‘Yes!’ Dolly says, recklessly. ‘Why don’t we pray for the President? If we’re having all these problems, why don’t we pray for Mr President?’

Abumrad finds this a profound statement — this is Dolly, after all — but feels obliged to note extenuating circumstances: Dolly has written songs supportive of labor rights and the plights of deportees and mine workers.

Abumrad was inspired to make the podcast when Dolly befriended his father, the doctor who took care of her after a 2013 car crash. Abumrad (creative writing and music composition at Oberlin) comes from a different world than Dolly (daughter of an illiterate sharecropper, school of life) or Jimi (alcoholic parents, high-school drop-out). Reverse the worlds, and perhaps Dolly would be a feminist playing the political ‘game’, as she calls it, and Jimi would be giving masterclasses at Juilliard. But that was not who he was or who Dolly is. And this is why their music still speaks best for them.

This article is in The Spectator’s October 2020 US edition.