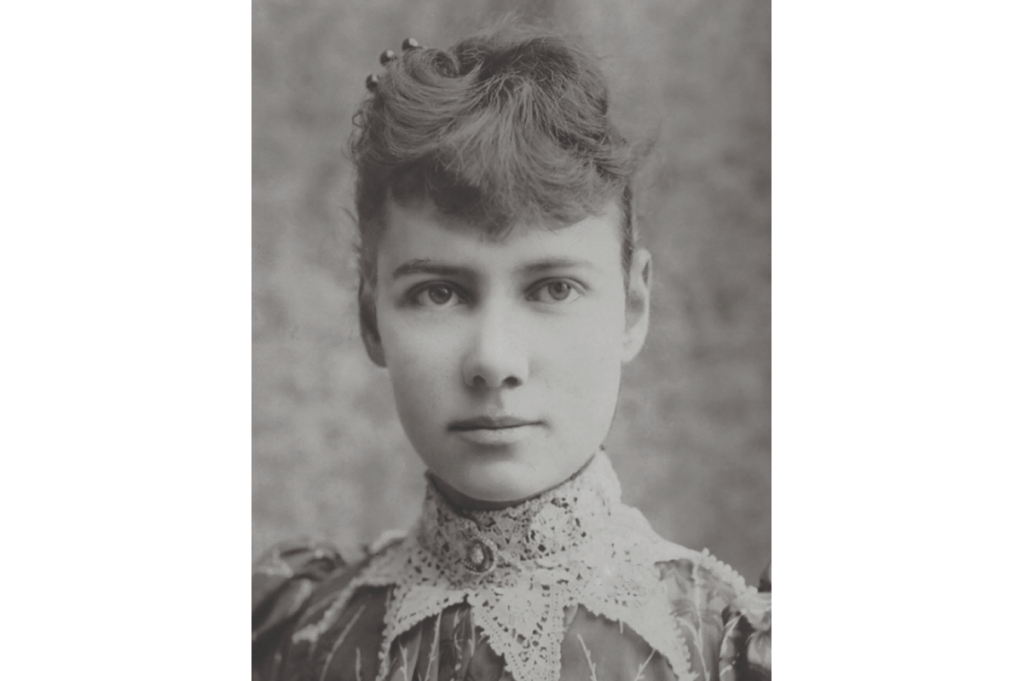

In the 1880s a new group of women was entering newsrooms. Not content to write society sketches or cover the fashionable hats of the season, they went for bold reporting — often going undercover or participating in other dramatic ‘stunts’. The antic that launched Nellie Bly’s career in 1887 was getting admitted as a patient on Blackwell’s Island in New York, then an insane asylum for women. She had told the editor of the New York World she would do anything fora job on the paper, and this was what she was assigned. She went to a boarding house under an assumed name, pretended to be unhinged and was duly committed. Rescued after 10 days by a representative from the World, her exposé of the indignities suffered by patients in the asylum was a sensation. Bly was on her way to becoming a household name.

Women could go undercover in ways men couldn’t — something the Pinkertons found when they first recruited female agents, and something newspaper editors were quick to realize. A woman can go to places that men cannot, and she is invisible in many social spaces. Nobody back then would have suspected a woman of being a detective (or a journalist).

Soon many American papers had ‘girl stunt reporters’. The trend brought hard-hitting coverage, but also sensational events: famously, a race around the world between Bly from the New York World and Elizabeth Bisland from Cosmopolitan magazine. They headed off in opposite directions, hoping to beat the 80 days of the fictional Phileas Fogg. Bly beat both Bisland and Fogg in real life.

Sometimes columns were written collectively, with several reporters using a pseudonym; this makes it hard to trace exactly who wrote what. The most intriguing section of Sensational is where Todd attempts to track the identity of ‘Girl Reporter’, an anonymous writer who in 1888 approached doctors in Chicago asking if they would provide an abortion. Her report, with a list of the doctors who agreed, not only launched a flurry of lawsuits by indignant physicians, but sent several of the doctors to prison.

Writing about abortion was a dicey proposition for a woman hoping to maintain a ‘respectable’ image, so it’s not surprising the reporter sought anonymity. Maintaining a veneer of respectability was like walking a tightrope for these women as they sought to write honest accounts of what they experienced while undercover. As Todd notes, Bly’s experience in the madhouse glosses over the risks of violence and sexual violation in a way that seems implausible today.

Of the women mentioned in Todd’s book, perhaps only Bly and Ida B. Wells will be names familiar to readers today. As white women were making waves as ‘stunt journalists’, African-American women like Wells were using journalism to campaign for civil rights. They could not afford frivolous (and reputation-endangering) stunts, but they were also opening doors for a new generation of female journalists.

For all their sensationalism, stunt journalists could also bring about social change. Bly’s asylum story prompted the government to spend $50,000 on improvements. Eva McDonald’s exposé for the St Paul Globe of conditions in a garment factory in Minneapolis sparked a strike. Showing readers precisely how badly workers were treated met with a receptive audience in the Progressive era.

But the climate for journalism changed after the Spanish-American War, ginned up by William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer in their competition for newspaper sales. The appetite for yellow journalism and its panic-and scandal-mongering fell away. And this included the appetite for stunt journalism, which in its excesses had seemed trashy. Some stunt journalists managed to change tacks, becoming ‘sob sisters’, women journalists focused on human-interest stories. Others left the profession to marry or pursue other lines of work.

It can be hard to keep track of all the characters in Sensational, with the cast of women journalists growing with each chapter. Todd has unearthed a whole biography for each of them and follows them through the end of the 19th century. These women came from a variety of backgrounds and were often drawn from the working class: journalism was their way out of having to be the factory girl or the maid they would pretend to be for stories. Today fewer journalists seek undercover scoops. Nor do editors hire reporters just for showing moxie, rather than a journalism-school diploma. More’s the pity.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2021 World edition.