One of the first jobs I ever did for The Spectator was to find out if professional wrestlers fixed the outcome of their fights in advance. This was 1965. The editor who wanted to know was Iain Macleod, a future chancellor of the exchequer filling in time while his party was out of office by dabbling in journalism. He turned out to be an addict of the professional wrestling screened on Saturday afternoon TV. In spite of the spinal disease that had immobilized his back and neck, he mimed what he meant by throttling himself without getting up from his chair in an Indian deathlock.

His deputy editor, his political editor and I watched this unnerving performance in horrified silence. ‘Wouldn’t it be better if we sent a man?’ asked the deputy editor after a long pause. ‘Don’t be silly,’ snapped Macleod. ‘If we sent a man, they’d screw his head off.’ So I set out to do what he asked. I was 24 years old at the time, and I learned more about life in the next few weeks than in three years at Oxford.

Afterwards I hung on at The Spectator as office dogsbody, useful for filling up the back end of the paper with features on ballroom dancing (this was 40 years before Strictly), comprehensive schools and plans to pedestrianize Piccadilly Circus. In the end they invented the title of arts editor to make the job sound more important, and found me an office in the attic, a dingy little room with a fishy smell and a skylight so small you had to keep the electric light on all day. After a series of embarrassing interviews with potential contributors, I discovered too late that the smell came from my light bulb, which was melting the fish glue on its cheap, ill-fitting lampshade.

At a time when the only professions open to women generally boiled down to nursing or teaching, The Spectator was a marvelous place to work. For one thing nobody ever objected that I wasn’t a man. For another, at any rate under Macleod, the political journalists running the front of the paper paid not the faintest attention to anything I did at the back.

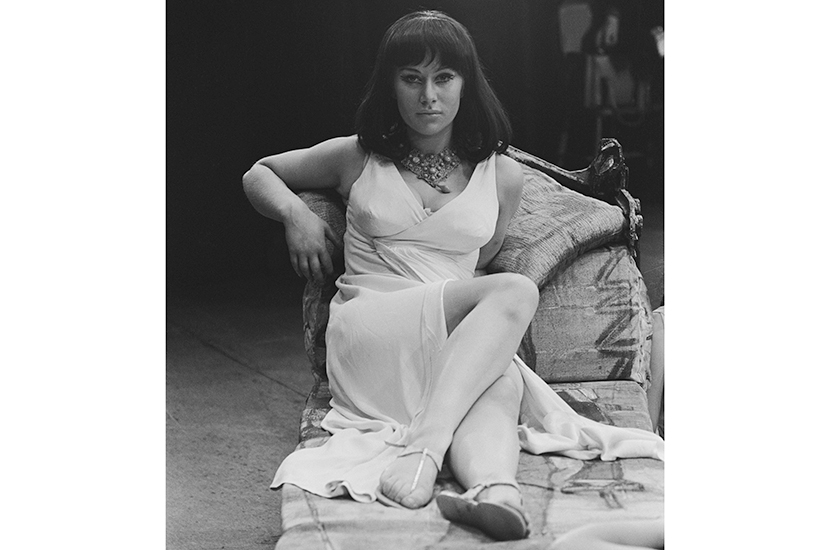

First I sacked the theater critic. After scouring the national and local press, I found Germaine Greer, then a postgraduate student newly arrived from Australia, who turned the job down in order to concentrate on her thesis at Cambridge. So I did it myself instead. My first column was about Helen Mirren, only a few years younger than I was, playing a stunningly sensual Cleopatra for the National Youth Theatre. Mine was the only professional review she got, and I correctly forecast her future as a great star.

The paper’s art critic had died just before my arrival and I replaced him with Bryan Robertson, director of the Whitechapel Gallery, which meant that The Spectator’s coverage of the first post-war wave of young British artists — headed by Bridget Riley and Anthony Caro — was second to none. As a counterweight I picked a professional art historian from the National Portrait Gallery called Roy Strong. A demure young bureaucrat in gray pinstripes when I first met him, Roy switched almost immediately to become one of London’s snappiest dressers, a flamboyant partygoer and formidable art-world operator in the 1960s and 70s.

My worst mistake was to turn down a friend who wanted to take over the film column. This was Jim Farrell, a burly rugger player who caught polio at Oxford and by his own account emerged from the iron lung a white-haired novelist. Sure enough, a few years later he published Troubles, the book that made his name as J.G. Farrell.

When Nigel Lawson succeeded Macleod as editor in 1966, I became his literary editor, taking over from a Welsh poet who gave me a single parting tip. ‘You’ll get a lot of invitations to publishers’ parties,’ he said. ‘Chuck them all in the wastepaper basket.’ I ignored his advice.

One of the things I liked best about this new job was the matchmaking involved. I invited Enoch Powell to write about Machiavelli. John Gielgud reviewed a reissue of his childhood favorite, E. Nesbit’s Five Children and It. Barry Humphries, first encountered as a rude strip cartoonist on Private Eye, contributed entertaining and scholarly pieces on 18th-century gothic novels.

Spectator parties took place in the editor’s big first-floor room in those days, and I’ll never forget Barry climbing on to the editor’s desk to sing a long, lewd song called ‘The One-Eyed Trouser Snake’. He was still relatively unknown but the force of his personality reduced an audience of high-powered journalists and Tory politicians — including a fair sprinkling of prospective or actual cabinet ministers — to something near silence as the words sank in.

I watched the back of the editor’s neck turn a rich purple. There was nothing I could do about what was fast becoming a public contest between two outsized male egos. In the end Nigel wrestled Barry off the desk, and my memory of what happened next is a blur.

I learned a lot from my stint at The Spectator and enjoyed it no end, but what I really wanted to do was write a book of my own, not review other people’s. So when Nigel left to stand for parliament in the general election of 1970, I left too, ending my journalistic career on a high note with a review of the greatest and grandest of all drag queens, Danny La Rue at the Palace Theatre: ‘A radiant siren with his curls and pearls and plumes, his bouffant hair and plunging necklines, skirts gored and split and slashed, his cyclamen-pink lips, six-inch heels and sumptuous legs…’

And if anyone wants to know the answer to Macleod’s original question, it seemed to me to lie in the fact that the trade union favored by professional wrestlers, probably by drag queens too, was the Variety Artistes’ Federation.

This article was originally published in

The Spectator’s 10,000th UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.