Whee-ooh-whee ya-ya-yang skrittle-skrittle skreeeek…is it a space pod bearing aliens from Mars? No, it’s a podcast featuring aliens from Venus: women sculptors.

If the intro music to Sculpting Lives: Women & Sculpture sounds like Dr Who, its two jolly presenters — Jo Baring, director of the Ingram Collection of Modern British & Contemporary Art, and Sarah Turner, deputy director for research at the Paul Mellon Centre for British Art — come across as younger, slimmer, artier versions of the Two Fat Ladies. ‘Jo can talk about Liz Frink’s work until the cows come home,’ Sarah informs us at one point before warning Jo: ‘You’re going to have to convince me a little bit. Dogs, horses…that’s what I think of when I think of her work.’

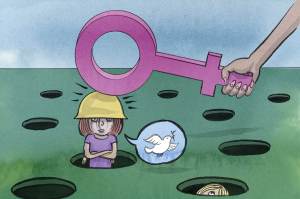

A better title for this five-part series would be How to Succeed in Sculpture Without Being a Man, and with children in tow. Between them its female subjects had 14 — Barbara Hepworth four, Elisabeth Frink one, Kim Lim two, Phyllida Barlow five and Rana Begum two — which was an image problem in a discipline traditionally regarded as male, as well as a test of time management. When Barlow arrived at the Slade in the mid-1960s her tutor Reg Butler told her bluntly that he wasn’t interested ‘because by the time you’re 30 you’re going to be having babies and making jam’. He then challenged her to name a woman sculptor ‘apart from Barbara…let me tell you, there are none’.

Barbara was the exception, the woman sculptor who got to play with the big boys by combining iron discipline with naked ambition. Hepworth was a hustler, tirelessly courting potential buyers, dealers and gallery directors: when Wakefield Art Gallery, now the Hepworth, couldn’t afford to buy a sculpture she had persuaded an early collector to offer at a discount, she got her father to buy it and give it to them. ‘She managed her brand, fair play to her,’ says one commentator. She managed her legacy too with the help of her son-in-law Alan Bowness, who five years after her death in 1975 became director of the Tate.

Contrast the case of Frink, the first woman sculptor to be elected an RA yet still not the subject of an academic study nearly three decades after her death in 1993. Blame the dogs and horses, which endeared her to the public but not the critics: ‘I went from having very good write-ups to very bad write-ups,’ she records. Simon Martin, director of Pallant House Gallery, finds her neglect ‘baffling’ but puts it down to ‘a sniffiness about figurative sculpture’. That doesn’t explain why the Singaporean-British abstract sculptor Kim Lim disappeared from view after her early death aged 61 in 1997, despite a tally of 80 works in UK public collections. ‘It’s amazing how quickly with the passage of time an artist can be placed on the periphery,’ observes Bianca Chu, curator of two recent shows at Sotheby’s S2 that have put Lim back in critical contention. The truth, perhaps, is that her art was never mainstream; her elegant concern with ‘form, space, rhythm and light’ owed more to nature than to male modernist abstraction.

Barlow’s story, thankfully, is more cheering. Instead of turning her into ‘a rabid feminist’ her Slade experience helped her muster a ‘tremendous single-mindedness’ which — after a 40-year career as an influential teacher — powered her late irruption, aged 73, on to the international stage with a magnificently unruly sculptural rampage through the British Pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennale. (Reg who?)

Male sculptors measure themselves against their peers, conscious of their places in the hierarchy; women sculptors, outside the hierarchy, go it alone. To the evident surprise of Jo and Sarah, none of their five identified as women artists; Lim didn’t even identify as Asian, politely refusing an invitation to take part in the Hayward Gallery’s 1989 Afro-Asian art exhibition The Other Story. ‘The sense of not belonging had the compensatory feeling of freedom,’ she said.

A lesson of this series seems to be that if you’re not pigeonholed you tend to get mislaid, but that doesn’t bother Rana Begum. Another graduate of the Slade who moved here from Bangladesh as a child in the mid-1980s, Begum is reluctant even to be defined as a sculptor, working as she does with everything from paint and fabric to neon, baskets and the reflective vinyl sheeting used in road signs. She struggles with ‘being boxed in one discipline’, just as she fought as a child to stay out of the kitchen: ‘I didn’t learn to cook because I knew I’d be in the kitchen cooking five curries a day. It took a while for my father to accept.’

As for Barlow, her entire oeuvre, with its carnivalesque collision of unorthodox materials, looks like a messy outburst against pigeonholing. The question is, how good is her jam?

This article was originally published in

The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.