I loved this book so much I was appalled. Why, when bookshops are stacked full of memoirs by authors who can’t write, isn’t Alexandra Fuller heaped up in perilous piles so near the till it’s impossible to evade her? This is like one of the most alluring Svetlana Alexievich testimonies, as if it had wandered out of the USSR and got lost in central Africa by way of a hospital in Budapest. It’s packed with exquisite jokes, quotes and details — such as when a doctor appears and ‘his gauzy green scrubs puffed out in great billows, the surgical-garb equivalent of Princess Di’s wedding dress’.

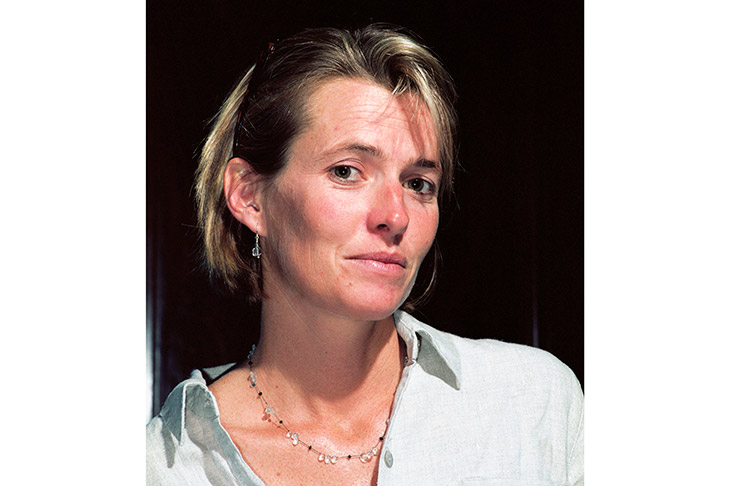

Fuller started out trying to write novels before putting her own parents down on paper. The first installment of their lives was the bestseller Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight, followed by the also wonderfully titled Cocktail Hour Under the Tree of Forgetfulness and Leaving Before the Rains Come.

This is the story so far. After a childhood of British ‘boiled-cabbage and gin-wrecked gloom’, ‘Dad’ met ‘Mum’ and together they fell in love with central Africa and embarked on a life of chaos. Fuller writes:

‘“I think your father mistook the sound of a champagne cork for the sound of a starting gun,” my grandmother said afterwards. “Your parents took off for their honeymoon at 100 miles an hour and they never slowed down for the corners.”’

They had five children, including Alexandra (known as ‘Bobo’), but three died in childhood. ‘If the Fullers had a code it was Keep Buggering On. If we’d had a coat of arms, it would have shown two rampant dogs, a shovel and a gun.’ All bearers of that surname are charming, but it’s Mum who has my heart. Her motto — ‘She wept bitterly in private; drank bravely in public’ — is now mine.

Of Africa, Mum explains:

‘People think it’s all pink gin and White Mischief all the time, but it’s not. Mostly it’s too hot for any sort of mischief, and there are snakes. You need the drink, for goodness sake. And your father insists we live a very spartan existence. I blame that mediocre boarding school he went to…’

Neither of them hold any commonplace opinions. Dad despises aid workers. ‘Go home. Piss off. Foutez le camp!’, he shouts, before inviting them to stay in the family’s ‘guest cottage’. (He doesn’t mention that it ‘lacked hot water, fans and a ceiling, and was preferred by the area’s breeding frogs’.) ‘Excitement of the week,’ he once wrote to Bobo. ‘Guest attacked by python in the library.’

Mum, meanwhile, isn’t at all happy with Bobo’s depictions of them. ‘You write very flatteringly of Dad,’ she complains of a previous book. ‘You’ve made him sound like Marcus Aurelius, all stoicism and bons mots, and you’ve made me sound like a racist alcoholic, forever oppressing the natives and swilling booze.’

This memoir begins — and is wholly preoccupied — with the death of Dad, who falls ill with pneumonia while holidaying in Budapest. Fuller recalls:

‘Dad didn’t look like a typical elderly, dying Englishman, pale and soft, untouched by an excess of ultraviolet light. He looked exactly what he was, a banana farmer from Zambia’s Zambezi Valley. Any moment, it seemed inevitable he’d sit up, swing his legs over the side of the bed, and say, ‘Right, no more silly buggers!’

But he doesn’t, and Bobo struggles to cope without him.

The last time one of her books was reviewed here, Elisa Segrave wrote what now sounds akin to a curse: ‘I long for her to return to Africa, or, if not, simply to write about it again and again.’ I’d repeat the sentiment, and demand memoir upon memoir, if it weren’t for the devastation that hits at the end of this book. It left me wondering what Fuller would have chosen: to have no gift, the dullest sort of parents and a life in which no one dies before their time; or to suffer, as she does here, but preserve the memory of those she loves most — so that perfect strangers might fall in love with them too.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.