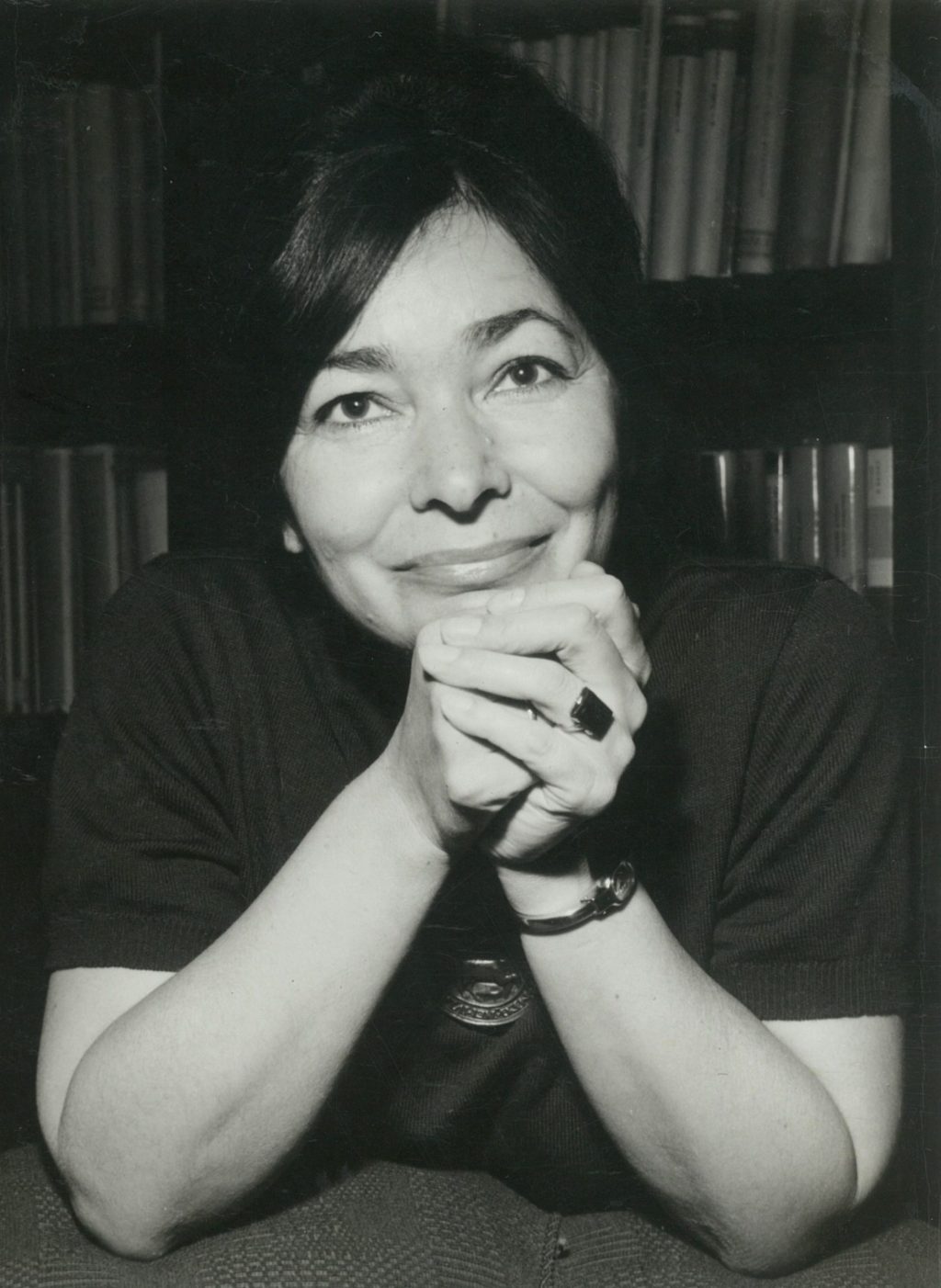

Although widely read in her native Hungary, Magda Szabó, who died in 2007, did not gain international acclaim until the mid-1990s with the translations of her novels The Door and Katalin Street. Abigail, which was originally published in 1970 and is her best-known book, now appears in English for the first time in a superb translation by Len Rix.

Set over six months, from September 1943 to March 1944 when Germany occupies Hungary, Abigail follows the 14-year-old Gina Vitay, who is ‘plucked away as if by a bird’ from her privileged life in Budapest and sent to a remote fortress-like Protestant boarding school for girls by her father, a general in the Hungarian army. Gina doesn’t understand why she has been uprooted or why she cannot tell anyone where she has gone (Szabó builds suspense by not explaining it until much later). Distressed and being bullied by the other pupils after refusing to take part in their childish games, she tries to run away. Then Abigail, the statue of a young woman in the school garden who, according to legend, has helped girls with their troubles, leaves a note for Gina under her mattress. What ensues is a thrilling unraveling of everything Gina thought she knew.

Throughout the novel, Szabó’s characters are vivid and amusingly authentic. During a church service, Gina’s inner monologue focuses on a handsome teacher sitting nearby:

‘It didn’t seem right that a man should have such beautiful eyes. At that moment she would have loved to reassure herself in a mirror that her own eyelashes were even longer than his.’

Szabó is skillful, too, at creating moments of heart-rending tension, often through exquisite, evocative prose. When Gina first arrives at the boarding school, for example, she is stripped of her expensive clothes, given a full-length black uniform to wear and told to take off the necklace that the general just bought her as a keepsake:

‘The little moon tinkled softly as it fell on the table in front of her father…both kept their eyes fixed on the carpet. The silence was like that when a bee wanders in through an open window and drones on and on without ceasing.’

Abigail sets up a world of two halves: the naive fantasies and ‘petty cruelties’ of teenage schoolgirls ‘who could think of nothing more’, and the somber realities of war (‘death and destruction, battles lost, armies in retreat, and the panic-stricken actions of a deranged national leadership’). It’s when these two collide that the novel has a devastating power. In a memorable scene, the girls — picking fruit on the school’s allotment — notice a couple of goods trains trundle past transporting troops.

‘All work came to a halt…the soldiers stopped singing and turned their faces to take in the sight of schoolchildren laboring in the countryside — young men on their way to the battlefront, gazing in silence at the girls and the apple trees.’

One of the teachers quickly raises an imaginary baton and the pupils launch into a song: ‘The soldiers are going away/ To defend our beautiful land.’

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.