‘Without this river the Russians could not live,’ remarked Robert Bremner in his Excursions in the Interior of Russia. The year is 1840. The river in question, the Volga, the 2,000-mile long meandering waterway stretching from the forests of northwest Russia to the steppes by the Caspian. At the time of Bremner’s survey, half of the Russian empire’s fish were caught in the single stretch of river by Astrakhan, the Volga’s final pit stop before flowing out to sea. Since the earliest days of medieval Rus through to the Soviet and post-Soviet eras, the Volga has not simply fed the mouths of its population but has been crucial to Russia’s commercial, cultural and imperial development. As a Vesti news report from 2019 simply stated: ‘Without the Volga, there would be no Russia.’

In her concise, lucidly written new book, the historian Janet Hartley takes this uncontroversial premise and excites it with drama. This isn’t a book about the Volga itself, but rather the river’s role — physically and symbolically — in the turbulent making of Russia. For those in search of a topographical survey from source to delta, look elsewhere.

In this 1,000-year marriage — a mere blip on the river’s ancient timeline — the Volga has been both active participant and indifferent bystander to seismic moments in Russia’s history. As the Mongol empire swept westward, the Golden Horde built their cities on its banks; the Cossack revolts led by Razin and Pugachev snaked the river’s lowlands; the Volga was Russia’s line in the sand in the battle of Stalingrad, as Stalin delivered his infamous, fateful order: ‘Not a step back’.

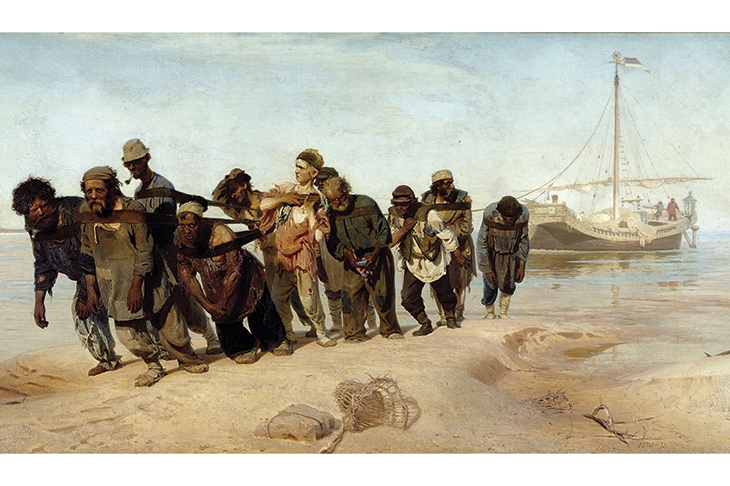

Hartley retells these already familiar stories as miniature dioramas, resisting digressions that take us too far from the water’s edge. Her companions here are not only czars, generals, peasants and explorers, but also painters and writers, such as Ilya Repin and Vasily Grossman, historians of feeling and mood. As with her previous work, Siberia: A History of the People, Hartley is as preoccupied by how people lived in the cradle of ‘Mother Volga’ as by the headlines the river wrote. In these pages you will find as much on the interiors of a Tatar home as you will on the formation of Moscow. Passing, ornamental details such as these are the book’s most delightful moments.

Catherine the Great described the Volga as the border between Christian ‘West’ and non-Christian ‘Asia’, a binary which underestimates the distinctly multi-ethnic, multi-confessional makeup of the Volga region. Tatars, Chuvash, Mari, Mordvins, Udmurts, Bashkirs and many other Russian, Turkic and Finno-Ugric peoples lived — and continue to live — among the elephantine arcs of the river, while in Astrakhan, Russia’s commercial gateway to the east, Armenians, Persians and Indians traded goods. This made Russia a rich, thriving market, but also caused headaches for its rulers. In framing the history of the Volga as largely the history of Russia’s attempts to stamp its authority and customs on a largely non-Russian region, Hartley has found an important and often disregarded story to tell.

The Volga is a comprehensive biography, but not necessarily a definitive one. Only a brief final chapter deals with the ecological costs of centuries of civilization and the more recent disruptions to its biodiversity from rapid, mismanaged industrialization under the Soviet Union. At just over 300 pages (plus an abundance of notes and dense bibliography), however, its concision should not be mistaken for thinness. This is a work of masterful condensation, commanding storytelling and an invitation to marvel at the ‘gloomy grandeur’ of one of the earth’s oldest residents.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2021 US edition.