To describe a new book as ‘eagerly awaited’ is almost unpardonable. Yet Mark Doty’s What is the Grass: Walt Whitman in My Life is exactly that. It’s not just that Doty is an extraordinarily fine writer whose every word sings on the page. Poetry has a tendency to come into its own at exceptional times such as our own. William Wordsworth’s 250th anniversary has provoked media reflections on his consolatory power; a recently established Poetry Pharmacy is receiving attention; and social media brims with poems and poets attempting to make sense of what’s happening to us. Arguably there couldn’t be a more apt context for Doty’s book about his lifelong exploration of — and through — the great American poet Walt Whitman.

There certainly couldn’t be a more appropriate explorer than Doty, as both a leading North American poet and a memoirist and prose writer of exceptional grace and depth. This genre-crossing book leads us on an exploration of Whitman’s work, regarding ‘Song of Myself’ as ‘a call to change our way of seeing self and other, a persuasive text that aims to revise our understandings of the most basic things. The poem wants to accompany us in the direction of awakening’.

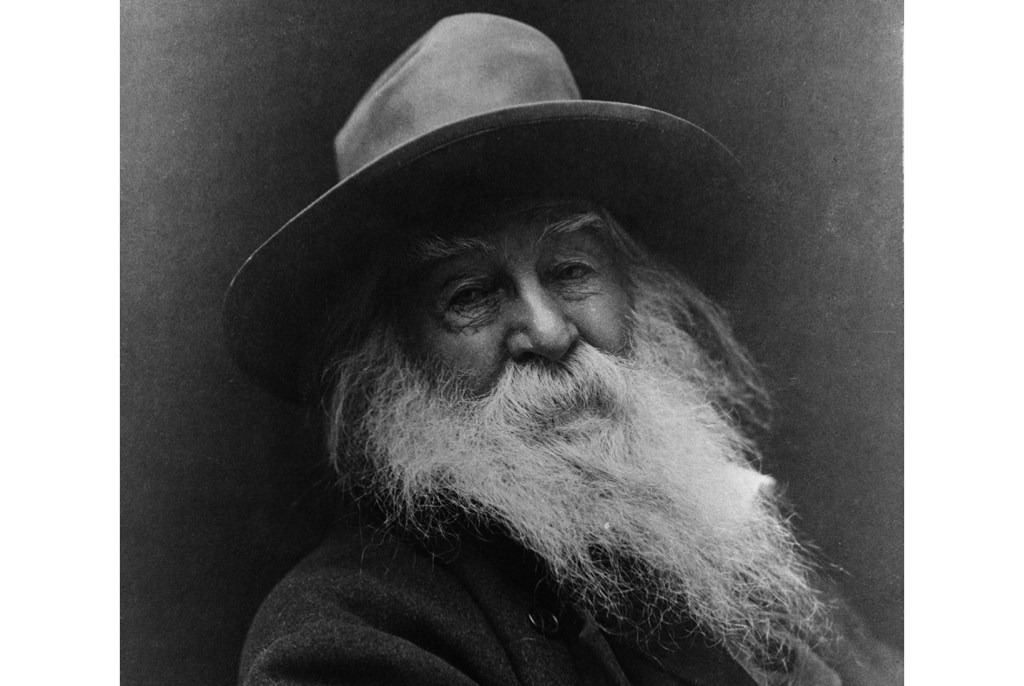

When he died in 1892 Whitman was still rewriting the epochal Leaves of Grass, first self-published in 1855. The man who wrote ‘I am large, I contain multitudes’ was as protean as his work — so charismatic that his extraordinary gaze survives even slow-motion 19th-century photography. He left school at 11, worked mainly in printing and journalism until the outbreak of the American Civil War, then moved to Washington, where he nursed wounded soldiers while holding a succession of minor civil servant roles. His death at 72, nearly 20 years after suffering a major stroke, was an occasion for national mourning. By then he was recognized as one of the great American writers.

While there may be other poets we reread as often, few have had such an influence on subsequent writing and thought. Whitman’s formally innovative, explosive praise songs for the natural world and emerging urban life, transcendence and sex have transformed what’s followed beyond the confines of the English-speaking world. He is an enormously important figure for any poet, particularly a fellow North American; and Doty’s own poetry and prose is recognizably Whitmanesque in its explicit humanity and its development of a spoken music which is flexible, modern and above all present.

He is also, like his great precursor, both a gay man and a poet committed to exploring themes of desire and relationship in contemporary life. His well-known collections My Alexandria and Atlantis and a series of prose memoirs starting with Heaven’s Coast deal with the griefs and terrors of the Aids crisis. Even his most recent collection, Deep Lane, explores how to live the good (gay) life. So, though past commentators have sometimes tried to play down Whitman’s sexuality, Doty brushes aside such demurral. His Whitman is the poet of self-discovery and radical encounter with the world: ‘I have instant conductors all over me […] They seize every object and lead it harmlessly through me.’

Of course, life isn’t quite that simple. Like Doty — as he reveals in a series of sharp autobiographical vignettes — Whitman also at times ‘masked’ what could attract social censure. But What is the Grass resolves the problem that ‘Whatever the dead did or did not do in bed is largely irrecoverable’ by returning to the poetry itself. The dead poet’s ‘body of work is his only body now, gorgeous, revelatory, daring, contradictory, both radically honest and carefully veiled’. Whitman’s writing visualises the world charged with masculine sexuality: ‘As God comes a loving bedfellow and sleeps at my side.’ (Doty also makes the point that Whitman writes warmly about women, but just can’t imagine female sexuality beyond the maternal.)

In place of the slightly persecutory work of biographical detection, then, Doty substitutes the pleasures of reading. And this multifaceted book is among many things a memoir of reading itself: of returning to a body of work that has been of enormous importance to the author and showing not only how astonishing it is, but how much it has shaped his own life. Passages of close reading fill What is the Grass, as they search for the sources of Whitman’s extraordinary invention. Doty identifies five: revelatory experience, gay love, the rise of the American city, the natural world and the demotic freshness of American English.

And then the memoirist’s lens lifts from the page to scenes from Doty’s own life as a gay man. He describes the body of an early lover as a ‘door’ through which he found his way into authenticity and self-understanding, and shows us how Whitman’s poetry has been another such life-opening door. Like Whitman, too, he leaves these doors open for everyone, regardless of gender or sexuality. This is an exceptional, passionate memoir of reading, and of a poet’s lifelong work of understanding self and the world.

This article was originally published in

The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.