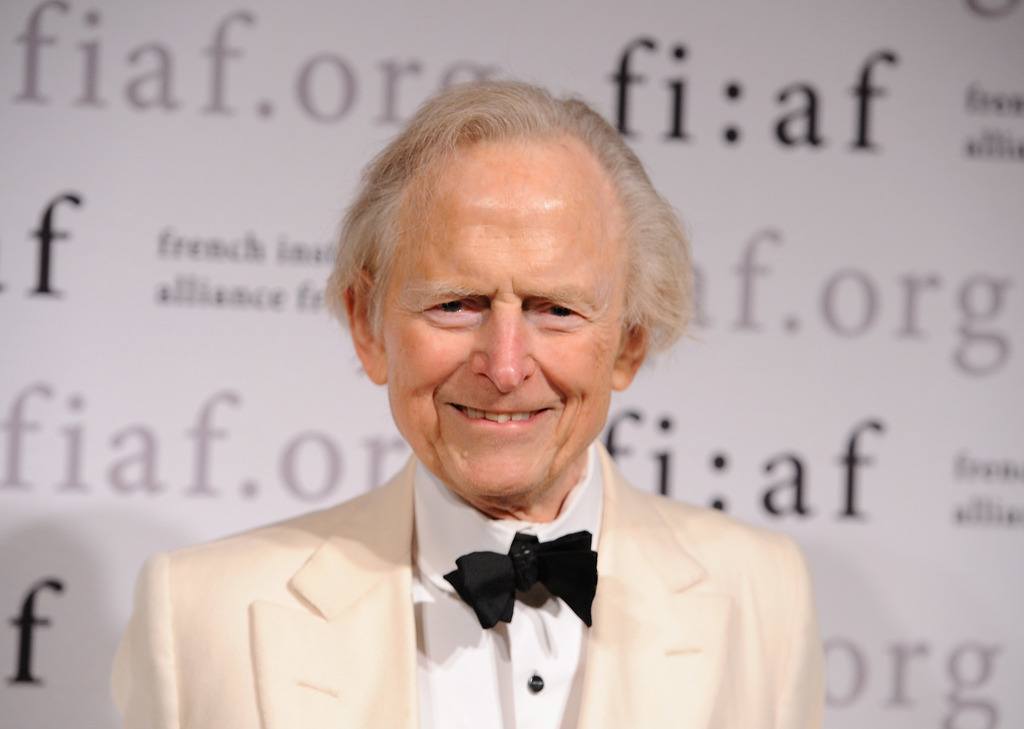

To some, Tom Wolfe’s death might seem a greater loss for readers on the right wing of American culture and politics, since he viewed himself as a conservative, very much in keeping with his upbringing in the Richmond, Virginia, of the 1930s and 1940s. His gentleman’s manners and soft-spoken demeanour recalled another era — a class-defined and racially segregated world of courtliness and formal collars. Wolfe famously picked on liberal targets throughout his remarkable career: his most savage satires addressed the pretensions of leftish icons from Leonard Bernstein to, most recently, Noam Chomsky.

‘Radical Chic’, his essay about infiltrating Leonard Bernstein’s party for the Black Panthers and Upper East Side liberal fashion in the late 1960s, still looms over Manhattan social life all these years later (no New York host or hostess ever wants a Tom Wolfe-type reporter sneaking into their fancy fund-raising party again), and it can still make you laugh out loud, even if you happened to support the Black Panthers. His last book, The Kingdom of Speech, poked fun at Chomsky’s theory of the origins of language, though the celebrated linguist and his followers were not amused in the least.

As a left-wing liberal, I feel the loss as acutely as anyone, since Wolfe was no conventional right-winger. On the contrary, he was a radical reporter and thinker of the sort we rarely see any more in America, which is becoming hidebound and politically correct, on both the right and the left, to the point of suffocation. In this, he was the most classic of liberals, open-minded, curious and willing to debate any issue. Over the nearly 40 years I knew him, Tom was never an ideologue and thus never dull-minded. He was always the arch opponent of orthodoxy in all its forms. That I could disagree with him completely about, say, the Vietnam War or the welfare state never lessened my admiration of his hostility to cant.

Wolfe’s literary and journalistic exemplar was Emile Zola, a reform-minded liberal who made the effort to learn about the real environments in which he placed his imaginary characters, whether they were poor and dispossessed or rich and ruthless. Wolfe liked to cite Zola’s extensive research for Germinal, the story of a miners’ strike, which included a visit by Zola to a working coal mine. Why couldn’t contemporary American novelists do this kind of reporting, Wolfe demanded to know of the literary establishment.

Not that he made the poor his cause. But his point was validated when he stunned the literary world with his first and most successful novel, The Bonfire of the Vanities. To write it, Wolfe learned the ins and outs of the Bronx criminal courthouse — the whole cast of judges, lawyers, clerks, defendants and cops — with an eye to detail that made his plot ring with authenticity. He was able to describe the high and the low of New York society without resorting to what he called the ‘absurdist’ anti-realistic approach to fiction that he claimed had been incubated in universities. In ‘Stalking the Billion-Footed Beast’, his much-attacked 1989 essay in Harper’s Magazine, he wrote, ‘By the mid-1960s the conviction was not merely that the realist novel was no longer possible but that American life itself no longer deserved the term real.’

So it made perfect sense when, at a Harper’s 150th-anniversary event held in 2000 in New York, Wolfe paid tribute to his political opposite, Seymour Hersh, who had read from his 1970 piece about the My Lai massacre in Vietnam. Hersh described how he tracked down one of the American soldiers who took part in the massacre, Paul Meadlo, on a farm in Indiana. Before the interview, when Meadlo’s mother greeted Hersh, she memorably told him, ‘I gave them [the army] a good boy and they sent me back a murderer.’ When he stood at the lectern, this was Wolfe’s response: ‘Something tells me that Sy Hersh and I disagree slightly about America’s role in the world and even the nature of wars in Vietnam.’ However, ‘We agree about one thing… we agree very strongly about the nature of reporting… And when I hear Sy tell about going to the trouble of going out into the middle of the United States and finding a mother who’s 50, and looks like she’s 75, looks a bit like a chicken on a chicken farm, and says what she said about her son, I recognise that as great reporting.’

Wolfe became so famous as a magazine writer, then as a writer of non-fiction books, and then again as a novelist, that his newspaper origins are mostly forgotten. Fresh from his Yale PhD in American Studies, he worked successively on the Springfield Union, the Washington Post and the New York Herald Tribune. The Herald Tribune in the 1950s and 1960s was a writers’ paper and it’s there that Wolfe’s talent for finding the telling detail was able to break through. In October 1962, an editor at Esquire, Byron Dobell, read what was, as I heard Wolfe describe it last year, little more than ‘a squib’ on page 13 that carried the byline Tom Wolfe.

The assignment was routine: Wolfe had been sent to cover a campaign photo op for Robert Morgenthau, a gubernatorial hopeful who needed an image remake because he came off as too stiff and serious. At Nathan’s Famous, the legendary Coney Island eatery, Morgenthau was obliged to take a hot dog and expected to eat it for the cameras. As Wolfe wrote, Morgenthau ‘does not toss smiles around -casually’, so when a photographer asked him to lighten up, he replied: ‘How do you eat a hot dog and smile at the same time?’ Against all rules of public relations, Morgenthau declined to eat either the hot dog or a kosher knish. At this point, most reporters would have let it go, but Wolfe followed the candidate beyond the ruined photo op: ‘Around on Fifth St, in the back seat of a car, Mr Morgenthau’s son, Bobby, 5, sat far back from the Boardwalk crowd. He was eating a knish. Somewhere, politics must run in the family.’

Dobell took note and a new, truly original style was launched in a national magazine. Only in New York, perhaps, and Tom Wolfe loved the city that gave him the chance to write. As his sometimes publisher and, I hope, his constant friend, I know that New York won’t be the same without him.

John R. MacArthur is publisher of Harper’s Magazine