I found Ta-Nehisi Coates’ book We Were Eight Years in Power surprisingly engaging. It combines a calm, friendly voice with a message of cold extremity. The message is that the sin of white supremacy is the true plot of US history. By trying to cure it, Obama exposed its true torrential force.

The geniality of the voice makes the message oddly persuasive. Coates uses memoir with great skill, presenting himself as a normal struggling bloke who had an amazingly lucky break. Writers normally sound as if it’s their absolute right to hold forth, that they deserve every column inch they get, and far more money. This humbler attitude (or pose, if you’re cynical) feels very fresh.

And it opens one to his radical reading of American history. In particular he makes this point with great force: the new nation’s egalitarianism did not just happen to be accompanied by racism. Rather, it was only possible for white society to move from aristocracy to democracy because of the enslaved underclass. It was the gulf between black and white that enabled whites to feel a new sense of brotherhood. And this gulf was not banished by the civil war and abolition. For the white majority still needed it there, and drew on it as it chose.

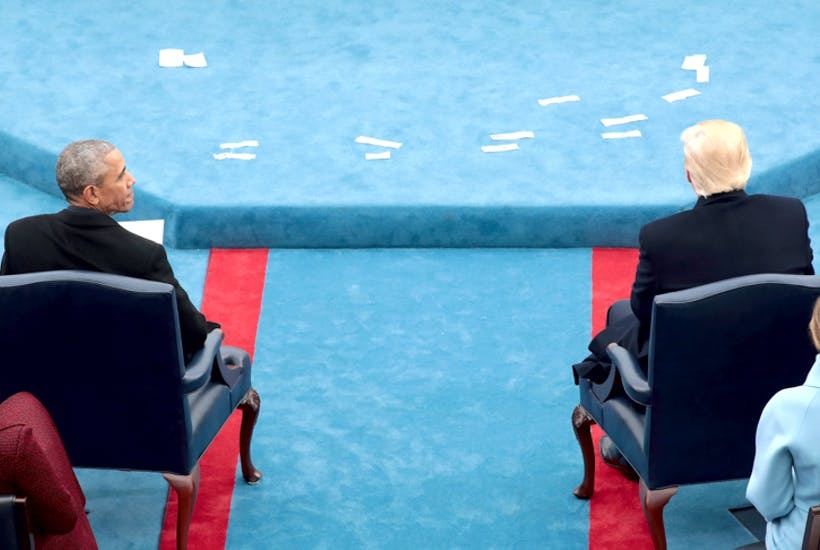

But don’t things change in the civil rights era? Not really, says Coates. For the nation did not fully and clearly repent of its founding sin. Widespread resentment at desegregation continued to influence policy, trapping blacks in poverty and in prisons. Normal liberal politics, even that of Obama, fails to demand a full reckoning with the extent of the ancestral sin.

It is very like the Marxist belief that gradual progress is insufficient – a revolutionary break is needed. Some have called Coates a fundamentally religious writer, though an atheist. This is right: his rhetoric is absolutist and impractical (unless you think reparations is feasible).

But in the end his ‘realism’ is excessively bleak. In reality the US did change in the sixties, officially ending its old exclusion of blacks. Did it fully repent? No, but a nation is not a single soul that can do such a thing. A racist rump remained, and has influenced mainstream conservative politics. Its erosion can only come from the old liberal idealism (with its Christian base), exemplified by Martin Luther King and Obama. But Coates’ voice is needed too, to remind us of the depth of the hurt, and the strange mythic basicness of the crime.