Academics at the University of Cambridge in Britain won a cheering victory for free speech on Wednesday when they voted by an overwhelming majority to reject plans from the vice-chancellor to change the rules governing debate at the university.

They rejected the university’s proposals to insist that students and staff be ‘respectful’ of opposing views. They decided, instead, that the rules should say students and staff must ‘tolerate’ opposition. The result was as close to conclusive as you can get. Only 162 academics voted in favor of the university’s plan, while 1,316 voted in favor of the change. (A further 208 academics wanted neither.)

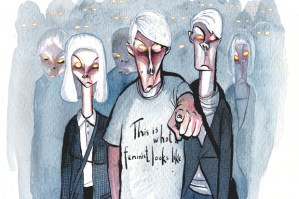

As I explained in The Spectator last week, the distinction between respect and tolerance goes to the heart of today’s raging debates on free speech. To tolerate an opponent is to refrain from punishing him or her for their views. You remain free to offend and challenge them. You most certainly have no obligation to respect ideas you regard as ignorant or dangerous or both. ‘Respect,’ by contrast, is a slippery concept that should set off alarm bells. Respect can be hard earned and freely given. Yet gangsters also demand it at the point of a gun. What version of the word did Cambridge mean when when it said staff and students must ‘respect’ differing opinions?

Could Cambridge ban an atheist speaker for refusing to respect religion? Or a feminist for failing to respect trans women? Should scientists treat anti-vaxxers with respect and hold back for fear of hurting their tender feelings and offending their dignity?

I know from trying last week that no one in the university’s hierarchy could answer these questions. Indeed Roger Mosey, former editorial director at the BBC and master of Selwyn College, later admitted, ‘In retrospect, respectful might not have been the word we should have chosen.’

Arif Ahmed, the Cambridge philosopher, who led the campaign to force the university to come out unequivocally for free debate, was gracious in victory. He told me he was sure that there was no malice on the part of the authorities. The debate seems very genteel. Very Cambridge.

Yet here is what is telling about it. As soon as anyone chose a side, you knew without needing to be told where they stood in today’s culture wars. The Cambridge branch of the University and College Union showed how hopelessly it has lost touch with its members when it recommended that they should not vote for Ahmed’s amendment. Ahmed said that his colleagues not only had a strong commitment to freedom of expression and academic freedom but were worried about threats to those who spoke out of turn.

Cambridge itself witnessed class-based thought policing recently when students at Clare College damned one of their porters as ‘unfit both to hold public office and to be in a position of responsibility over students.’ Kevin Price was a Labour party councillor as well as a porter. His crime was to refuse to accept a motion from his local party that stated ‘Trans women are women. Trans men are men. Non-binary individuals are non-binary.’

Students, largely drawn from the middle and upper classes, were trying to get a working man fired because his views, expressed outside the college workplace, did not conform with current left orthodoxy. The right may exaggerate the threat to freedom of speech in the universities, in part as cover for its threats to the BBC. But that does not mean that there aren’t real fears. Academics, public sector workers, liberal journalists and artists can all cite examples of intimidation and censorship and of the cloying culture of fear that follows.

Until they began to be repealed in the 1850s, Oxford, Cambridge and Durham universities required students and lecturers to undergo a theological test and to swear allegiance to the monarch as supreme governor of the Church of England. The tests excluded Catholics, non-conformists, non-Christians and atheists: everyone, that is, who was not an Anglican or not willing to pretend to be an Anglican.

[special_offer]

It’s not hard to feel in liberal institutions that there are new tests, and you must agree with or pretend to agree with the articles of the progressive religion if you want to get on, or at least be left in peace. Ross Anderson, professor of security engineering at Cambridge, told me he and his colleagues were concerned that, if the rules weren’t changed, unscrupulous operators would exploit the university’s bureaucracy as they fought ideological and personal feuds.

Anderson issued a call to arms when he appealed to academics to defy the vice-chancellor. ‘Liberalism is coming under attack from authoritarians of both left and right,’ he said, ‘Yet it is the foundation on which modern academic life is built and our own university has contributed more than any other to its development over the past 811 years. If academics can face discipline for using tactics such as scorn, ridicule and irony to criticize folly, how does that sit with having such alumni as John Maynard Keynes and Charles Darwin, not to mention Bertrand Russell, Douglas Adams and Salman Rushdie?’

Anderson might have added John Milton to his list. Milton graduated from Christ’s College, Cambridge, in 1629, and said in his Areopagitica, the first and finest defense of free speech in the English language, ‘Give me the liberty to know, to utter, and to argue freely according to conscience, above all liberties.’ Almost 400 years on, it is great to see his successors affirming the same principle.

This article was originally published onThe Spectator’s UK website.