Palaces, art galleries, parks, composers’ houses, operas, concerts, Spanish Riding School horses, full-throated choirboys wearing sailor suits…yes, I go to Vienna for all these delights. But, deep down, probing my true desires and motives, I really go there for the coffeehouses. It’s just that to make the coffeehouse experience the most delicious it can be, you need to arrive cold, hungry, intellectually stimulated and with aching feet from visiting one of the above attractions.

Then you’ll feel the warmth seeping into you as you sink down onto a coffeehouse banquette. Because who on earth would choose to sit on one of the exposed central tables, with hard wooden chairs, when you can sit around the edge at a table in a window bay, on a seat as comfortable as the softest 1930s railway carriage seat?

The atmosphere of the great old Viennese coffeehouses — they seem to have been founded between 1824 and 1899 and are mostly still in private hands — is uniquely delightful. I’ll try to get to the bottom of why.

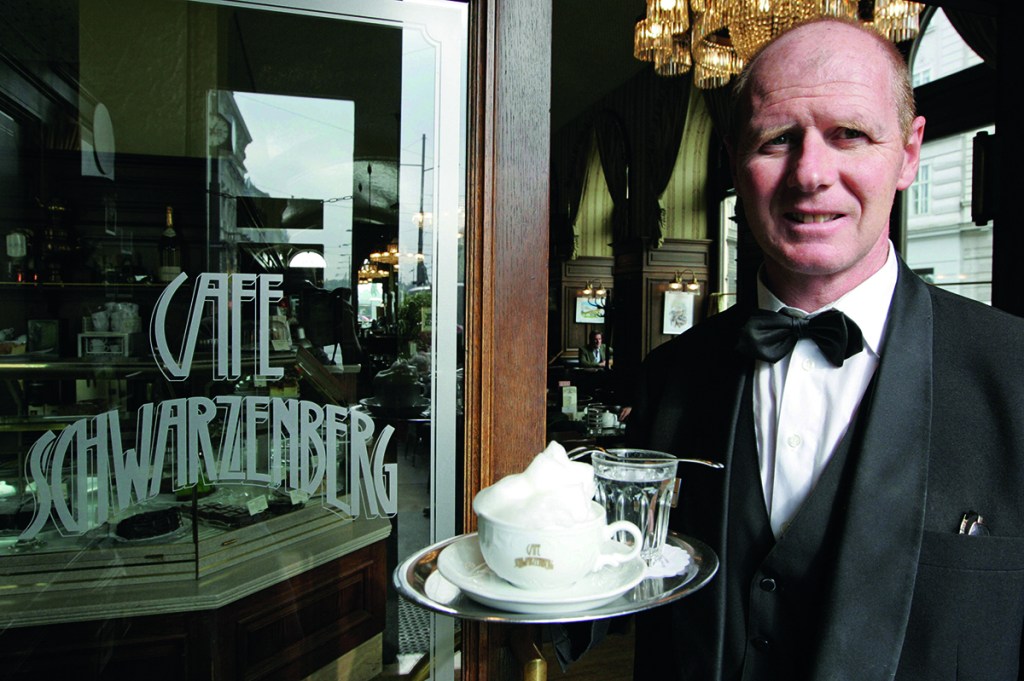

Depressing though it is, it almost helps (for contrast’s sake) that there are now 13 Starbucks outlets in Vienna. Nip into one of those for 20 seconds, just to remind yourself of the weird Starbucks muffiny smell, the lines, the sameness in whichever country you are, the need for a receipt code to use the bathroom, the buckets of milky calories being handed out, the always disappointing sawdusty flapjacks. Why would anyone go to a Vienna Starbucks (though lots do, for familiarity’s sake) when you could go to Demel, the Landtmann, the Bräunerhof, the Frauenhuber, Prückel, the Schwarzenberg or the Tirolerhof, all of them elegant havens where a waiter in black tie and black waistcoat will look after you in just the right way, with the perfect degree of attention?

They look like they’ve been working there for decades, those waiters, all of them men. I did speak to one having a quick cigarette outside the Frauenhuber; he had indeed been a coffeehouse waiter for 48 years. But they’re not pompous like the café waiters in Paris or Cannes who pretend not to notice you for the first 25 minutes. They’re quietly, proudly, charmingly Viennese, and they want you to have a nice time and not feel pressed to vacate your table. So, hang your coat on the nearest wooden coat-stand, sit down and watch how the locals do it. They wander in, sometimes alone, sometimes with a partner or friend. Many of the men look like Stefan Zweig, who used to do exactly this. Their actions have an air of the habitual. They take a newspaper from the row of newspapers hanging from a rail, each clasped in its wooden newspaper-holder. They sit down and read their paper of choice, drinking their habitual coffee of choice, either alone or in companionable silence, pausing (if with a partner) only to discuss the review of a performance of a string quartet they’ve just heard. It’s all extraordinarily civilized.

What makes this sharing of newspapers in wooden clasps so special? I think they enhance the sense of givenness, the sense of sharing the information of the day and the feeling of ‘absolutely no rush’. There’s a complete absence of takeout lines and bustle. These are places to collect and mine one’s thoughts, either in company or alone.

Demel is the most famous of the Viennese coffeehouses, and for that reason now not my favorite, because it does actually occasion waits for the upstairs-seating part, and you need to book in advance to dodge them. And it’s not even independently owned any more, having been taken over by DO & Co restaurants and catering. And next to our table there were two gormless tourists in baseball caps staring at their phones. It didn’t have the quiet, understated, almost library-like ‘nurturer of the mind’ atmosphere that I expect from a Viennese coffeehouse. But the miniature Demel Sachertorte with whipped cream, with a cup of velvety Demel hot chocolate, was unforgettably good. Demel is allowed to call its Sachertorte ‘Sachertorte’ because Eduard Sacher actually invented the cake while working not at the Sacher Hotel but at Demel. After years of legal disputes about this, all is settled, and the Demel version has the thin layer of apricot jam just under the top layer of unctuously shining chocolate icing, while the Sacher one has the apricot jam in the middle.

If you choose the moment just right, the spot-hitting qualities of Kaffeehäuser really can dazzle. Peckish, elated and a bit chilly at 9:53 p.m., after a long day of sightseeing ending with a concert of Beethoven violin sonatas at the Musikverein, we crossed the Ringstrasse, and there was the Café Schwarzenberg to welcome us in. Window bay, radiator, Spritzers, discussion of concert, professional waiters in black tie, generous but undaunting menu. And for me the most warming, flavorsome Gulaschsuppe imaginable, with a Viennese Semmel (bread roll) and butter (which I had to ask the waiter for, and which he shimmered off to fetch like a Viennese Jeeves). You can’t tear yourself away from such a situation of warmth, comfort and refuge abroad, so we lingered for coffee with cherry brandy, whipped cream and pistachio brittle: the ‘Mozart Coffee’, as it’s called on the menu.

The whipped cream on top of hot drinks thing is odd, really, because it automatically makes the hot drink less hot. In one of the Sacher Hotel’s own cafés (their new, dashing art nouveau ‘Salon Sacher’ to the left of the hotel entrance), I had the famous Viennese Melange mit Schlagobers — cappuccino with whipped cream on top. You have to go at this with a spoon, digging in past the cream, which causes instant spillage, and then you have to try a spoonful of the Sacher’s famous whipped cream on its own — outrageously good and light — and then you try sipping and get a whipped-cream mustache, so then you give the whole thing a stir, which lowers the temperature of the whole thing to lukewarm and causes a mass inundation on the saucer. But it’s all a huge pleasure.

The word ‘latte’ has still, thankfully, not entered the vocabulary of these hallowed places. Instead, we have poetic Viennese names for forms of coffee, such as the Einspänner, which means a one-horse carriage, an early form of taxi. This consists of two shots of espresso topped with a very deep layer of whipped cream, the cream keeping the black coffee just warm, like a white duvet. This is why it has that name: the waiting one-horse carriage driver liked it because he could keep his hands warm by cupping them around the bottom half.

Is there still a slightly male feeling about these places? The Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra was famously (notoriously) the very last to admit females into its ranks, with a violist in 2003. So Vienna is slightly behind the curve when it comes to feminism. Looking at the people reading their newspapers in coffeehouses this year, I did count more solitary men than solitary women, though this is changing.

You still get the sense that Freud, Mahler or Zweig might walk in at any moment, unaccompanied by any woman, and hang his hat on the hatstand while deep in thought. Freud favored the Café Landtmann on the Ringstrasse, which is still as splendid as ever. The young Zweig, also a Landtmann regular, prided himself on never getting any fresh air, even during the summer months. He and his friends spent hours of each day in the Landtmann, poring over the theater and concert reviews in the Neue Freie Presse and dreaming of getting their own reviews published in that very paper. Long may this intellectual coffeehouse atmosphere continue, unstifled by the phone-scrolling crowd.