This article is in

The Spectator’s December 2019 US edition. Subscribe here.

P.J. O’Rourke

I love poems but hate poetasters, love wine but detest oenophiles, love food but can’t stand foodies. Therefore my favorite passage about food in fiction is Lionel Shriver’s entire book Big Brother. In her tale of obese totalitarianism and comestible-fascists Shriver destroys every pretension and abstract conception about food — starves it to death or fattens it for the kill. And she does so in prose that is poetry: ‘You have to ask yourself if there was ever a time people just ate something and got on with it. Every time I open the refrigerator I feel like I’m staring into a library of self-help books with air-conditioning.’

Taki

When Papa Hemingway was not standing up writing in longhand, or fishing or hunting, he spent his time eating and drinking with friends and followers. His last big theme was, like his first, bullfighting in Spain. It was 1959, and he called it The Dangerous Summer. In the car, ‘I kept a cold bottle of the light rosado in the ice bag and ate bread with a slab of Manchegan cheese with it.’ Pepica’s restaurant in Valencia (which still exists) was ‘a big, clean, open-air place and everything was cooked in plain sight. You could pick out what you wanted to have grilled or broiled and the seafood and Valencian rice dishes were the best on the beach.’ At his old haunt of Marceliano’s in Pamplona, ‘The wine was as good as when you were twenty-one, and the food as marvelous as always. The faces that were young once were old as mine, but everyone remembered how they were… Nobody was defeated.’

John R. MacArthur

We’ve all had enough of Hemingway, I know. His Moveable Feast foundered long ago on the shoals of Americans-abroad cliché. Yet my favorite literary food scene — more memorable than anything I can think of in novels of greater quality — takes place in The Sun Also Rises when Jake Barnes and Bill Gorton go trout fishing on a hot summer day in Basque country. The two friends, bonded by survival of the Great War, land plenty of fish, but that’s not the important thing. Before they cast their lines, Bill suggests that Jake place two bottles of wine, presumably white, into the frigid water of a nearby spring. Later, when he drinks the ‘icy cold’ wine with its ‘faintly rusty’ taste, Bill exclaims with pleasure that it ‘makes my eyes ache’. The accompanying picnic — of chicken drumsticks and hard-boiled eggs — sounds better than any haute cuisine you might find in a more refined fictional setting.

Artemis Cooper

The servants have already hauled the table, chairs, and hampers full of meat pies and cold fowl up the steep slope of Box Hill in Surrey, and it’s a lovely day for a picnic. Everyone is aiming to project an artless simplicity in keeping with their picturesque surroundings — yet the party are all uncomfortable and nothing goes right. Frank Churchill flirts outrageously with clever, sparkling Emma; and when one of Emma’s witty remarks scores a direct hit on poor, garrulous Miss Bates, Mr Knightley forces her to confront how grievously she has hurt that lady’s feelings. We all have those moments that make us wince with remorse; but this scene is so raw I can’t help wondering if Jane Austen herself did something similar, and eased her conscience by giving herself a stern scolding through the voice of Mr Knightley.

Freddy Gray

My favorite book is The Brothers Karamazov, and my favorite part is not the famous passage about Elder Zosima’s corpse, nor the mind-bending monologue of the Grand Inquisitor. It is the scene in which Dmitry, the eldest brother, madly in love, broke and full of despair, stops at Volovya station. As he waits for his horses, ‘some fried eggs were fixed for him. He ate them instantly, ate a whole big hunk of bread, ate some sausage that turned up, and drank three glasses of vodka. Having refreshed himself, he cheered up and his soul brightened again.’ Something great about that: human misery, no matter how desperate, can be alleviated, at least temporarily, by eggs and hard liquor.

Cathy Erway

Early on in Knut Hamsun’s Growth of the Soil is the most beautiful passage I have ever read about potatoes. It is written from the point of view of the novel’s protagonist, Isak, who builds a home in undeveloped rural land in Norway around the turn of the 20th century. I love that it’s about food that is primal, essential sustenance — and he’s not waxing poetic about its taste but its resilience, versatility and purpose, crowning it a ‘lordly fruit’. ‘Not the blood of a grape, but the flesh of a chestnut, to be boiled or roasted, used in every way’. This book made me see potatoes in a new light — instead of a humble crop that caused famine for other Europeans, this was an exciting New World import that created opportunity for Isak.

Lara Prendergast

Eloise is six years old, and as all her fans know, she normally resides at the Plaza in New York. But in Kay Thompson’s Eloise in Moscow, she decamps to the National, which is on the corner of Gorky Street, ‘if you know where that is’. The place smells of chicken. She invites us to join her for a meal there and takes us through the menu. ‘It is difficult to know what to eat in Moscow’ because Russian food is ‘absolutely Russian’. There is borscht, of course, which is ‘not even red’ but ‘enough for lunch’. Melon isn’t in season and she usually decides on the curd cakes, but also favors the black caviar from the Caspian Sea, ‘which is fish eggs’. Nanny orders an egg, but then changes her mind because it comes with a feather. She goes for the beef Stroganoff sturgeon instead. Weenie, the pet pug, has a schnitzel. Eloise wishes she could have strawberries and cream. The food sounds revolting, Soviet cuisine at its most gelatinous — and yet, ever the diplomat, she knows to say it is good. ‘It is absolutely not,’ she whispers to us, but ‘you have to be careful what you do and say in Moscow’. Eloise is wise beyond her years.

Nina Caplan

Every era regrets the one before, but an age that teeters between bloated excess and willed abstinence has good reason to sigh over the unrepentant enjoyment that mid-20th century America managed so well. A.J. Liebling was a war journalist and sportswriter, but even they have to eat, and he was also a poet of indulgence: his writing never lets you forget that there is no such thing as too much when the quality is right. Picking a favorite essay from Between Meals, the too-slim collection of his best food journalism for the New Yorker, is akin to being asked, as a wine writer, to name my favorite bottle, but I will opt for ‘A Good Appetite’. Nominally the story of Yves Mirande, a gourmand of epic capacity, it is actually a disquisition on the dangers of restraint for anyone who aspires to write, eat or live well. (Liebling has difficulty disentangling the three, and who can blame him?) When his restaurateur mistress retires, Mirande allows his other mistress to reduce his vast intake of excellent food and wine. The results are first painful, then fatal. The moral is clear: do not stint, dear reader. If you are offered two cassoulets when you intend to consume only 18 oysters and a steak, you must polish off the lot, with three bottles of Champagne, for fear of offending your host, distressing your friends and marring your own future happiness.

Lillian Li

My parents told me that there was a tongue inside every persimmon, to explain the almost cartilaginous snap between my teeth whenever I took a bite. Ever since, I’ve seen the persimmon as the most sensual of foods. I’m not alone. Elaine Castillo’s wondrous recent debut America is Not the Heart celebrates the intimacy of this fruit in a scene between two women who are on the verge of love. Hero, a former doctor for the New People’s Army in the Philippines, is recovering after a government prison camp where both her thumbs were broken. New to America, she meets Rosalyn, a hairdresser who sparks a part of Hero that trauma had buried away. The scene has the two of them in the backyard of a house party, momentous because this is the first time Hero speaks about what happened. All the while, she struggles to eat a persimmon that Rosalyn has plucked from a nearby tree, her thumbs awkward and aching. Rosalyn then takes the fruit from Hero’s hand and bites into it herself. And then, ‘Rosalyn placed a small fragment of persimmon—invisible, saliva-wet, juice-sticky—into the center of Hero’s open palm.’ Together they feed Hero who finds, with every bite, that she cannot help but put her hand out again for more.

Wendell Steavenson

The most indelible meal I ever read in literature is created from hunger not feast. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn opens his magnum opus The Gulag Archipelago with a passage describing a scene in which a prehistoric frozen stream was discovered in Kolyma, in the Siberian Arctic, ‘and in it were found frozen specimens of prehistoric fauna some tens of thousands of years old. Whether fish or salamander, these were preserved in so fresh a state… that those present immediately broke open the ice encasing the specimens and devoured them with relish on the spot’. Those greedily gulping ancient slime were zeks, among the millions who were starved and worked to death in Stalins’s gulags. Solzhenitsyn had been among their number and The Gulag Archipelago — non-fiction, not a novel — is his testament. Heavy and comprehensive, it is a surprising page-turner. Solzhenitsyn was a writer who understood the power of the compelling detail. The image of the devoured salamander (devoured with relish, no less!) is so awful and amazing that I have never forgotten it.

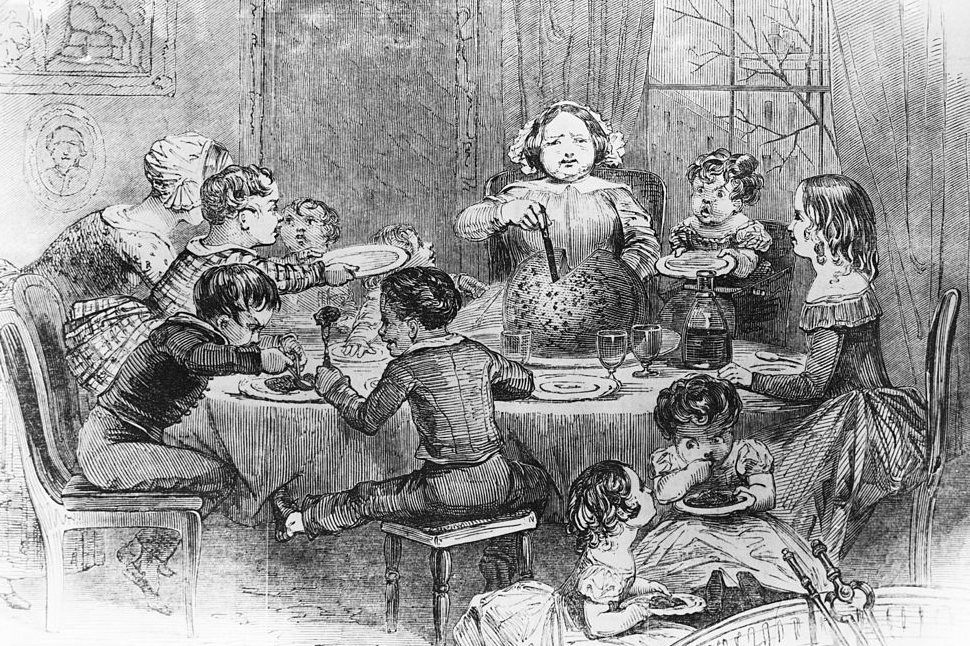

Dominic Green

As I’m Jewish, I eschew the pork pie that Pip’s awful aunt Mrs Joe sets aside for her Christmas party in Great Expectations. Pip doesn’t get to eat it either, because he steals it and gives to it Magwitch the convict. If my life were a Dickens novel, I’d be Pip. My late father, who was determined to make a gentleman of me, called me ‘dear boy’ as Magwitch calls Pip, and I called my father ‘Aged P’, as Mr Wemmick calls his father in the novel. In a further gastro-literary twist, I smuggled packs of Mr Kipling’s Apple Pies to my father’s study when my mother had put him on a diet —and in London rhyming slang, a ‘pork pie’ is ‘a lie’. Then there’s Miss Havisham, who has her cake but doesn’t eat it, and the two endings to the novel. I have no idea what all this means, but my wife, who despite my best efforts only occasionally reminds me of Estella, tells me that Freud calls this the ‘psychopie-thology of everyday life’.