I belong to a dying breed. Well, not a breed exactly, but a dwindling number who witnessed a world and a way of life that will never be repeated: we are the last babies of the British Raj. In my view the doyen of our group was the writer Charles Allen whose many books, starting with Plain Tales from the Raj, are almost all about the India he left at eight years old. He and I were on the same ship coming ‘home’ in 1948: the SS Franconia. So were more than a thousand other British men, woman and children, from typists and missionaries to engineers and soldiers, sailing away from India for the last time, leaving behind the graves of perhaps two million other Brits.

Allen died last year aged 80. I am writing this because those of us who remember anything about those times have to be around that age, or over. India became independent in 1947. Do the maths. We are not going to be around for long.

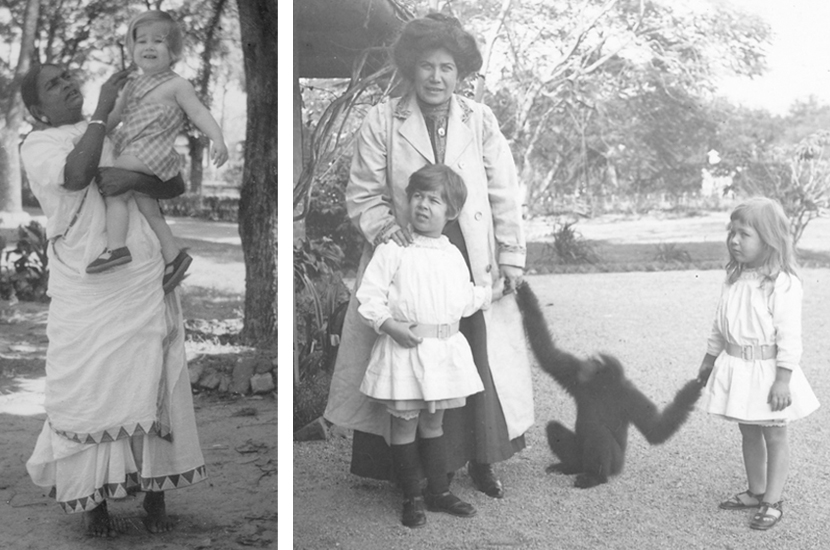

We Raj babies remember an extraordinary Technicolor world in which monkeys, elephants and camels lived among us and not in zoos, where buffaloes grazed in fields and cows roamed city streets. Mysterious and magical things happened in this world: men dressed in skirts and big bright turbans, and the women who repaired the roads looked like queens or princesses in swathes of vivid cloth. We were told extraordinary tales of men who could put swords through their cheeks or sleep on beds of nails. Every now and again we would glimpse a scary sadhu, a holy man, almost naked and smeared with ash. Joanna Lumley, who was born in India but came to Britain from Malaya when she was eight, remembers the sounds of other religions: ‘Chanting, tinkling bells, murmuring deep horns and the muezzin calling, it all seemed normal and commonplace.’

In our world, journeys took weeks by ship, or days by train, where we sat and slept in carriages cooled by giant blocks of ice slowly melting into metal tubs on the floor. Lumley again: ‘Packing and moving — these were so common I still feel uneasy if there is not a plan for travel ahead. It made me feel free, as though I belonged on ships and trains, rootless, always a member of that tribe, the wanderers who were called British but knew nothing of their homeland.’ Perhaps most importantly, we Raj children remember the people who worked for our parents: the cooks, bearers, gardeners, drivers — and especially the ayahs (nannies) who looked after us and whom we mostly loved with all our hearts. Growing up with them made us colorblind for ever. ‘Discrimination seemed particularly shocking and incomprehensible,’ says Lumley about the England she found on her arrival there.

What I have described was the good part of being born in the Raj. But there was a bad part too: the notion that the British had to be educated in England or they wouldn’t be ‘proper’. It caused untold pain and misery. The Indian writer Pankaj Mishra has said that it wasn’t only Indians who were punished by colonialism, but also the children of the Raj. They were separated at five or six from their parents and their familiar Indian homes and thrust into a cold, pinched, black-and-white, foreign world of relatives they didn’t know — or worse, of paid foster families. Kipling’s story ‘Baa Baa Black Sheep’, based on his own childhood in such a family, will break your heart if you have never read it.

I don’t have to look far to find broken hearts in my own family. My older brother was taken back to school in England by my parents in 1938, just before he was 10. My father, like other British officers in the Indian army, had home leave every two years, so they would meet again in 1940. In the meantime, my brother would be taken care of in the holidays by aunts and a grandmother. Except that the war came in 1939 and David did not see our parents again until 1945, when they were able to come back from India. They left a little boy and came back to a young man. He was far from being the only child to whom this happened.

The war saved me and my contemporaries from a similar fate. By the time it was over, Indian independence was on the cards and the need to send us army children back to be ‘civilized’ at school in the UK wasn’t urgent; we would be going there anyway. But some of the children of men whose work in India was unaffected by independence were still sent back in the cruel old style.

Julie Christie’s father was a tea planter and she was taken ‘home’ aged five by her mother on the first ship to leave India after the war, and left there. Her brother followed later. ‘I have no doubt that my brother and I were permanently emotionally damaged by the experience, even though my mum did try and come home on leave — about three times I think, with an extra visit when I was expelled from the boarding school I was attending. But neither my brother or myself feel sorry for ourselves, just hardened.’ Christie didn’t remember much and never gave India a thought until she went back there to film Heat and Dust in the early 1980s. ‘All that changed, I felt extraordinarily at home,’ she says — so much so that she went backpacking and exploring rural India ‘never feeling fear’. She has been a frequent visitor since.

The impact that our Indian childhoods had on us Raj babies seems to bear out that old Jesuit saying: ‘Give me a child until the age of seven and I will show you the man.’ The prizewinning writer Lee Langley, 11 when she came to Britain, says ‘India was fundamental to my thinking and attitude to life; to my sense of color and smell and awareness of scale… I still remember how small everything seemed when I came “home”, small and gray and cold.’

Our Indian roots, which in many cases (including mine) went back generations, gave us broader horizons, a wider perspective; they taught us to think outside the box, beyond color and class. But they also created in us all a feeling of being different, not being part of anything. ‘I never felt I belonged in England,’ continues Langley. ‘As a child I never did buy into that “home” thing about England, and when I got here, I definitely felt alien. And just as not feeling I belonged anywhere, I’ve never felt I belonged to a group of any kind. I’ve always lived with a sense of exile. For a writer, I think this is not at all a bad thing.’

Christie agrees: ‘Never feeling “English” or having a “home” anywhere — nothing wrong with that.’ And Lumley relishes the rootlessness her childhood gave her: ‘I have always felt as free as a bird; and the greatest dread was to be trapped behind a desk with a steady job. I was, and am, nostalgic for insecurity. The thought of acting jobs a year ahead still makes me feel panicky. The dogs bark, the caravan moves on. That’s the life for me.’

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.