Just as tastes in female beauty have differed widely through the ages — take a comparative glance at the damsels Rubens featured with those of Botticelli (I leave the Venus of Willendorf out of account) — so, too, does the taste in wine vary through the ages.

The British critic George Saintsbury was a giant in the field of literary scholarship. He was also an avid apologist for wine, and his Notes on a Cellar-Book (1920) is a classic in the literature of wine writing. A modern reader, however, cannot help but be struck by the prominent place given to wines that have fallen out of favor today, especially such fortified wines as sherry, Madeira and port.

Indeed, after some preliminary observations, he begins the book with a chapter on the first two and then proceeds with an entire chapter devoted to port. Claret and Burgundy share a chapter, and although he pronounces the wines of those regions ‘glorious’, Saintsbury indulges in a series of mild deprecations throughout the chapter. He notes the vogue surrounding the great Pauillac Pontet-Canet, but sniffs, ‘I never cared for it.’ St Emilion as a whole — even the stupendous Cheval Blanc — suffers a similar deflation. ‘I certainly do not wish to say anything against them,’ Saintsbury writes, but ‘I have never much cared for them.’

But about fortified wines — wines, that is to say, that have been ‘improved’ by the additions of spirits and (often) some form of sugar — he waxes rhapsodic. Tasting dinners featuring several wines are not uncommon. Saintsbury is unique, I think, in once assaying ‘a fully graded menu and wine-list with sherry only to fill the latter’.

My years in graduate school probably coincided with the last possible moment that a teacher would think of offering his students a glass of sherry. I once had a tutorial on Plato with the great Platonist Robert Brumbaugh. We met weekly for about an hour in the late morning. At the conclusion of class, before we repaired to luncheon, he would pour us both a small glass of sherry. Under the dispensation of the new puritanism installed by the triumph of political correctness, such rituals are probably actionable, even though (or perhaps because) they brokered important educational moments.

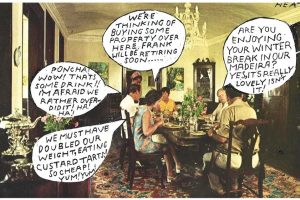

Madeira is even less popular than sherry these days. Were it not for the pudding zabaglione and Flanders and Swann’s classic ‘Have Some Madeira, My Dear’, I am not sure it would register in contemporary consciousness at all.

Port is a different matter. It’s by no means as common as it once was, but in serious households a good bottle of vintage port frequently marks the conclusion of a celebratory or holiday meal, especially in the winter months.

A single swallow does not a summer make, but Ports of New York Winery may be a herald of a change or augmentation of the winds of fashion in favor of a revival of interest in fortified wine. This small, artisanal winery in Ithaca, New York has been in business only since 2003. But Frédéric Bouché, the founder, comes from a medium-long line of French winemakers in Bordeaux and then Normandy. He emigrated with his American wife in the 1990s, and they set up in business together.

‘In starting this winery, we decided we didn’t want to do yet another Riesling, yet another wine that was well-represented here,’ Joanna Bouché told a recent interviewer. ‘We also wanted to work with Frederic’s background, his knowledge, his traditions, so the style of wines that we offer, for the most part, are different from what most wineries do.’

This is true. At the moment, they make two table wines, a white (Sancerre-like and predominantly Sauvignon Blanc) and a red (a Medoc-like blend of Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc and Merlot). Both are a reasonable $18 and are marketed under the label ‘Quotidian’, a Latinate word meaning ‘daily’ (as in ‘Give us this day our daily bread’). The grapes in all their wines come exclusively from the Finger Lakes region.

But I think Ports of New York is more celebrated for its two fortified ‘specialty’ wines called Meleau, a Latin-French coinage joining mel (honey) plus eau, as in eau de vie. Both are $48. The red is a sort of port, a mix of Cabernet Franc and Merlot with Noiret, a recent hybrid developed by agricultural scientists at Cornell University. Started with a dollop of honey-fed yeast, the fermentation is stopped by a dash of brandy to ‘fortify’ the wine. It weighs in at about 17 percent alcohol, lighter than a typical port, and with a modest 6 percent residual sugar. It’s not Taylor’s or Quinta Do Noval Nacional, but it is perfectly agreeable and worth trying.

The same is true of the white, a golden, sherry-like wine that is predominantly a blend of Muscat Ottonel and Vignoles, again with a dash of spirits added to stop fermentation. It, too, is light on alcohol, which means that, were Professor Brumbaugh still teaching class, he could offer two glasses instead of one before luncheon.

For more information, see www.portsofnewyork.com. This article is in The Spectator’s October 2020 US edition.