Raclette is the ultimate comfort food. From the French word racler, to scrape, this simple, hearty dish is all Swiss. There isn’t a village in Switzerland, in the Alps, the Jura or the Engadine, where you can’t have raclette. There are even restaurants, called carnotzets, just for raclette, although they usually serve fondue, as well. Many Swiss homes have their own raclette-designated space, often in the basement, sometimes doubling as bomb shelter, featuring fireplace and wooden table, with cozy banquettes. It’s where the Swiss go when they want to soak up carbs for comfort.

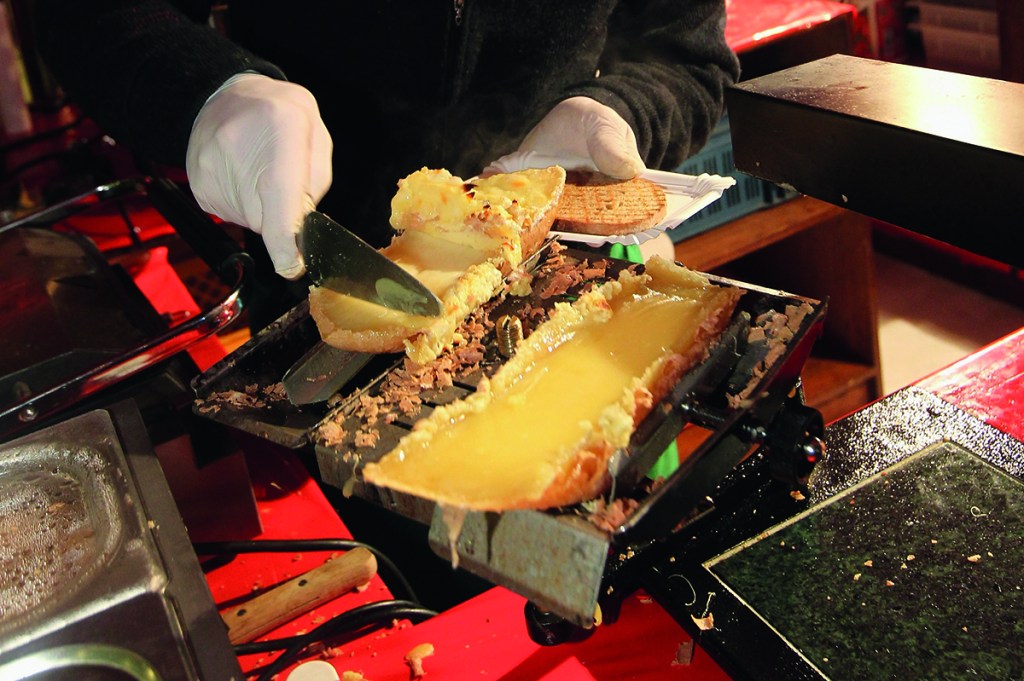

In the film Heidi, you’ll watch the orphan’s uncle serving her raclette in the rustic chalet during a cold winter’s eve. The uncle stands before the open fire with a half wheel of cheese, waiting till the top layer melts just enough to scrape onto his niece’s plate of boiled potatoes, gherkins, onions and dried meat.

One doesn’t order a ‘dish of raclette’, one orders ‘raclette’ — like ordering ‘fondue’. But that (and of course the melted-cheese aspect) is where the comparison ends. Whereas fondue has become an international winter tradition and many French ski resorts offer raclette, the French themselves often prefer tarteflette, a casserole of Reblochon cheese, bacon, potatoes and onions.

Fondue fans will argue for hours which cheese is better, what’s the best white wine to melt the cheese in, whether one should add cream (as they do in Neuchâtel) and how much kirsch is necessary to get zip. Raclette devotees are content passing condiments, meat slices and pepper grinder, chatting while watching their cheese melt.

Raclette’s simplicity was born of necessity. Swiss farmers, having to spend long, lonely months in mountain chalets, brought with them giant wheels of cheese, potatoes, pickles, onions and viande de Grisons, all of which would keep. As the chalets had fireplaces, it was easy to cut a chunk of the wheel, hold it in front of the blazing fire and scrape layer after layer onto small boiled potatoes, arrosées with pickles, onions and dried meat — carbs, protein, calcium and fat for the cold, winter months.

When I moved to Switzerland in 1967, my introduction to raclette was through an invitation from my neighbor Eliane. When she invited me for a raclette, I didn’t know if she meant dinner. The only clue was the hour — 7:30 p.m. The table was set for seven, and at one end, instead of another place setting, sat this huge machine: a kind of space heater-cum-Cuisinart.

Eliane laughingly explained that if she’d told me the ingredients I might have declined. All those carbs? (Though the carbs come mostly from the potatoes, not the cheese itself.) The simple dish’s merits were soon revealed as Eliane scraped and I tasted.

Back then, this was how hostesses served raclette. Long gone were the days when the chef du chalet had to stand in front of an open fire for each raclette serving, scraping continuously and starving. Then a Swiss Rube Goldberg invented a machine that made the Swiss national dish accessible to all. What he hadn’t invented was a way for the racleur to also eat. Eliane spent the whole evening scraping and serving, grabbing gherkins, onions, meat — here and there — as she melted cheese on demand.

Several years later, a raclette machine was invented that sat in the middle of the table with individual ‘pockets’ into which everyone could melt their own cheese. Maybe it was in 1971, when Swiss women got the vote. I immediately bought one.

My three children never asked for mac and cheese. They asked for raclette. Even when we moved to Brussels, raclette continued to be served chez nous weekly in winter. When we moved to our summer house on Cape Cod, the raclette machine moved with us. It got plenty of use. Raclette was our comfort food, while I oversaw the modernization of a hundred-year-old cottage in the middle of winter. The kids still talk about that winter. We had raclette so often they wondered if I could cook ‘American’ after living abroad for 21 years. They teased me about how I tried to educate Chatham with my raclette stories. If you are a winter resident of Cape Cod, with its inevitable Nor’easters, frigid temperatures and power outages, you need as many friends as you can get. Raclette was the perfect ‘ice-breaker’.

One of my favorite stories was how the Swiss have a yearly event to see how many raclettes a Swiss can eat at a time. The record was 43, and he died. That winter, I discovered that Monterey Jack worked quite well, as I couldn’t find raclette cheese on the Cape. Now it’s in most cheese shops. I also discovered that you don’t tell those you invite for raclette about the ingredients for the same reasons Eliane didn’t tell me — carbs. Unless, of course, they know about raclette. Then they jump at the invitation.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s February 2021 US edition.