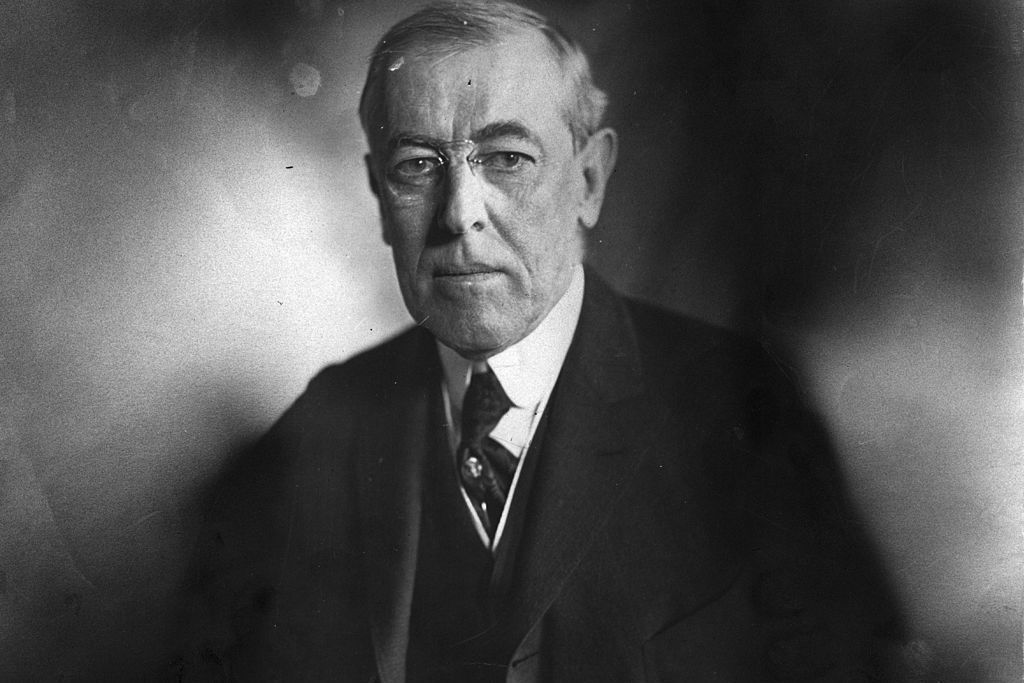

On November 18, 2015, a group of Princeton University undergraduates calling themselves the Black Justice League, or BJL, invaded historic Nassau Hall and occupied President Christopher Eisgruber’s office overnight, refusing to leave until Eisgruber had agreed to, and signed off on, their list of ‘demands’. Most famously, they demanded the purging of Woodrow Wilson’s name from the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs and from one of the residential colleges, Wilson College. At the time, Eisgruber promised to form committees to discuss the students’ demands; skillfully sidestepping the controversy. Today, however, nearly five years later, Eisgruber has announced that Wilson’s name is coming down.

Removing Wilson’s name was, and is, mostly symbolic. The BJL knew that this demand would attract attention to their cause, but they were more interested in their other goals: the institution of mandatory cultural competency training for students and faculty, a new academic requirement in the study of non-Western and marginalized peoples, and both a ‘safe space’ and ‘affinity housing’ for black students. In the last week, renewed calls for changing the name of the Woodrow Wilson School have been combined with demands for curricular reform, anti-racist training, reparations, divestment from the prison-industrial complex, and defunding campus public safety. The name is just the tip of the iceberg.

And for that reason, when 10 of us — black, white, Hispanic, conservative, liberal, male, female, gay, straight, able, disabled, Jewish, Christian, atheist — formed the Princeton Open Campus Coalition, or POCC, in response to the protests in 2015, we were far more concerned by the BJL’s threat to academic freedom than we were by the prospect of dishonoring a mediocre and admittedly racist president of the United States (albeit a pretty good president of Princeton). The BJL and their supporters, in addition to their specific demands for the ideological re-education of students and faculty, generally cultivated an atmosphere on campus in which other students would not — could not — disagree with them. Accusations of racism followed those who anonymously voiced their dissent on the social media platform Yik Yak, and black students who spoke out against the protest were instantly labeled ‘white sympathizers’, or ‘not really black’. It was clear that there was widespread disagreement over both the methods and the demands of the protestors, across campus and across the racial and political spectrum; however, unless students came together to dissent publicly, the administration and the outside world would see a student body seemingly united behind the BJL.

With our widely read open letter to President Eisgruber, POCC won the battle, but the BJL is evidently winning the war. Alumni who once whispered to me that they supported academic freedom are now taking to social media to join the call for anti-racist training. I like to believe that they do not know what this means — that they do not realize they are promoting not tolerance, but indoctrination. As a liberal student once wrote to POCC about her experience with ‘cultural sensitivity training’ at Wesleyan, ‘We were told these would be honest, vulnerable conversations for us to dig deep and understand our biases. The truth was that each of us recited lines. This was not open dialogue. We all know the script.’

[special_offer]

Is Eisgruber’s concession to the mob an indication of more concessions to come? Or is he throwing a symbolic bone in hopes of keeping students out of his office, if and when the University reopens in August? Either way, I think, we are ever closer to reaching what Plato in the Republic considered to be the final stage of democracy: ‘A teacher in such a community is afraid of his students and flatters them, while the students despise their teachers or tutors. And, in general, the young imitate their elders and compete with them in word and deed, while the old stoop to the level of the young and are full of play and pleasantry, imitating the young for fear of appearing disagreeable and authoritarian.’