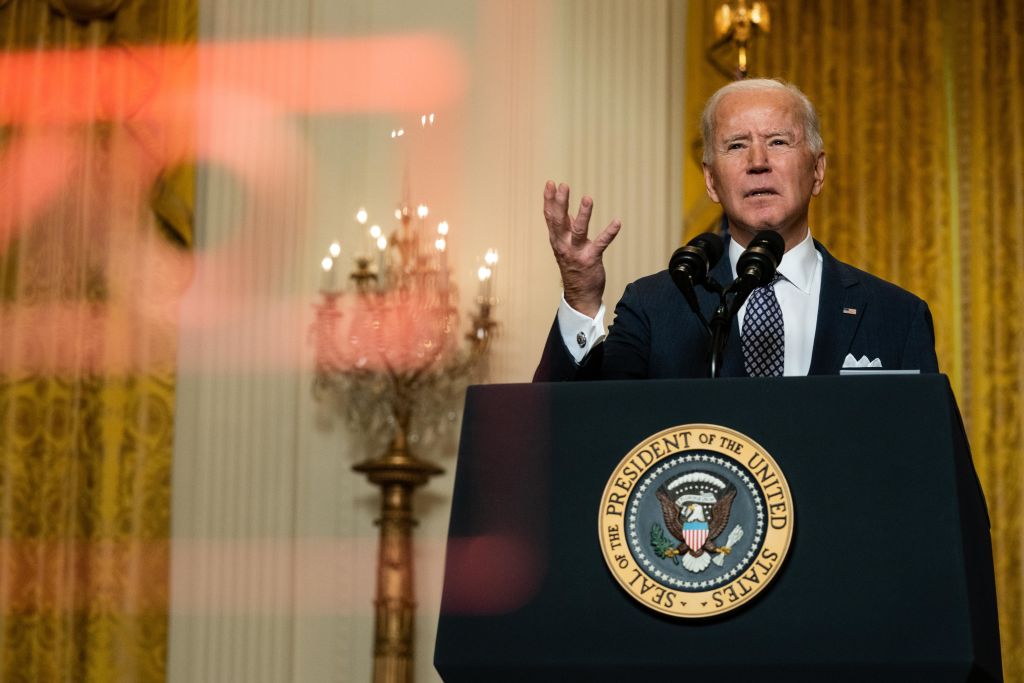

‘America is back.’ Speaking to the 57th annual Munich Security Conference, Joe Biden made that point for the umpteenth time in his short presidency. His crisp declarative sentence requires decoding, of course. To his audience of European elites, he was offering this assurance: ‘Trump is gone and won’t be returning anytime soon: trust me.’

In expanding on this basic thesis, Biden’s presentation covered a totally predictable range of topics and reached totally predictable conclusions. While repeatedly insisting that history had reached ‘an inflection point’, he simultaneously reiterated the claim made by every US president since Harry Truman (Trump excepted) that ‘the partnership between Europe and the United States’ will determine the fate of humankind. As a consequence, he asserted, that partnership ‘must remain the cornerstone of all that we hope to accomplish in the 21st century, just as [it] did in the 20th century’.

According to Biden, in other words, the US-led Eurocentric geopolitical order dating from the immediate aftermath of World War Two remains fully intact. So too, therefore, do all of the arrangements discussed, negotiated and affirmed by American, Canadian and European elites over the course of the previous 56 Munich Security Conferences. The barely-disguised purpose of these annual pilgrimages to southern Bavaria has always been to sanctify the existence of a so-called North Atlantic community, aka the West. As a participant in past Munich conferences, Biden himself needs no persuading. If ‘America is back’ has a corollary, it’s captured in the phrase ‘Nato now and forever.’

Of course, Biden did not actually attend this year’s Munich conference. Given the ravages that the coronavirus has inflicted on various Nato member states, the event’s conveners prudently decided to hold it virtually. Yet the symbolism was difficult to overlook: with Americans and Europeans beset by the deadliest threat they had faced since World War Two, leaders of the alliance said to guarantee their mutual security found it impossible even to gather in the same room. The ‘cornerstone’ was irrelevant to the proximate danger.

Rather than reflect on the disconcerting implications of that fact, Biden directed the preponderance of his attention elsewhere, alluding to a panoply of security challenges that figure as standard administration talking points. A ‘long-term strategic competition with China’ came first, followed by Russian troublemaking and the ‘global, existential crisis’ of climate change. Arms control got a nod, as did the imperative of addressing ‘Iran’s destabilizing activities across the Middle East’.

Biden also pledged that for now at least US troops would remain in Germany. This was the closest he came to a big reveal. At this supposedly pivotal point of inflection, the best the American president could come up with was to sustain a military presence created seven decades earlier in response to conditions that no longer exist. At gatherings such as the Munich Security Conference, this qualifies as enlightened statesmanship.

Washington’s own disastrously destabilizing activities across the Middle East over the past two decades went unmentioned. So too did increasingly desperate US efforts to conceal the fact that the Afghanistan conflict, the only real war in Nato’s entire existence, is ending in failure. Immigration, another hot button issue in both Europe and the Western Hemisphere, also escaped presidential attention. Biden’s survey of the relevant landscape was notably selective.

When speaking to domestic audiences, Biden positions himself as a champion of ‘equity’. Among American progressives, it’s widely accepted that those victimized by past racist policies merit compensation. Speaking to the heirs of empires that vigorously exploited non-white subjects as long as it paid while even today struggling to assimilate the formerly colonized, Biden was mute on the subject of compensation. At the Munich Security Conference, imperialism — whether the old-fashioned European kind or the American-preferred informal style — is off-limits for discussion.

Instead, Donald Trump’s successor found solace in ideology, telling his listeners that America’s European ‘partnerships have endured and grown through the years because they are rooted in the richness of our shared democratic values’. Those partnerships are ‘built on a vision of a future where every voice matters, where the rights of all are protected and the rule of law is upheld’. The present-day moment of inflection, according to Biden, pits ‘those who understand that democracy is essential’ against those who believe that ‘autocracy is the best way forward’.

As Nato members such as Poland, Hungary and Turkey succumb to intolerance and illiberalism, this democracy vs autocracy construct is facile at best. Given the fact that a handful of years ago Americans installed a narcissistic demagogue in the White House with over 74 million voting just last November to give him a second term, a reasonable person might wonder about the health of democracy in the United States itself.

I hope and pray that the January 6 assault on the Capitol was a one-off event. But what if it’s a precursor of things to come?

If the West’s strategic competition with the People’s Republic of China pits democracy against autocracy, it’s not clear that the odds favor our side. Assurances dating from the 1990s that Chinese economic development would lead inevitably to political liberalization have not panned out. In Beijing, the Communist party remains fully in control with President Xi Jinping wielding absolute power.

The future will no doubt bring surprises. That said, an economically preeminent, technologically sophisticated, and militarily incoercible China that is stubbornly resistant to the Western conception democracy presents itself as a likely prospect. Yes, American music, films and video games will remain globally popular for the foreseeable future. Students from abroad will continue to flock to campuses in the United States. American English will remain the global lingua franca. But the idea that a US-led bloc of Western nations will determine the future of the planet will become increasingly implausible.

It’s that very prospect that should concentrate the minds of US policymakers, who should consider the possibility that instead of a strategic competition with China it may make sense to negotiate terms of mutual coexistence. In that regard, a useful first step might be to forego future attendance at the Munich Security Conference, which remains captive of a past that may be pretty to look at but has become an obstacle to clear thinking.

Andrew Bacevich is president of the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft.