Modern tyrants have always looked to antiquity for models of how to exercise and display their power. For Joseph Stalin self-improvement did not mean listening to more audiobooks or enrolling in bi-weekly meditation classes. A lifelong bookworm who kept improbably long office hours, Stalin enjoyed reading about Peter the Great and Ivan the Terrible. Yet the most heavily annotated work in his 20,000 volume library was an account of the rise and fall of the Roman Empire by his favourite historian, Robert Vipper. The terrible, godlike power of the Caesars was something he could relate to. Adolf Hitler, taking a more dilettantish route, looked to classical aesthetics in painting, sculpture and architecture to infuse German culture with his ideas about race.

Nations do not slide into dictatorship anymore than they can import democracy from the outside. A dictatorship, like any system, must be created and sustained. Hence the concern of modern tyrants for the strategies and stylings of their historical predecessors. Stalin and Hitler were looking at blueprints from the past to guide their decisions in the present.

This month’s bloated New Yorker profile of Mark Zuckerberg, written by Evan Osnos, reveals that Zuckerberg is also enthralled by the power ancient tyrants wielded, the Emperor Augustus in particular.

‘I think Augustus is one of the most fascinating. Basically, through a really harsh approach, he established two hundred years of world peace,’ Zuckerberg told Osnos.

‘What are the trade offs in that? On one hand, world peace is a long-term goal that most people talk about today… that didn’t come for free, and he had to do certain things.’

Is there anyone else who would feel much more comfortable if Zuckerberg had simply told the New Yorker that he loved playing golf and watching Always Sunny in his spare time? Zuckerberg’s brain is poached with this obsession: his second daughter is called August. Osnos does not seem perturbed by these details, instead framing the profile in terms of the traditional (well, since 2016) liberal anxieties about Facebook: What is the moral character of Silicon Valley? What is the conscience of its leaders? Can Mark Zuckerberg fix Facebook before it breaks democracy?

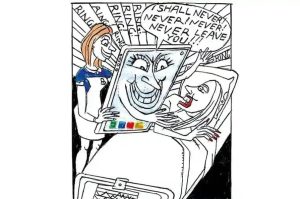

These are questions that might have been useful to ask ten years ago. In the meantime Zuckerberg and his lieutenants have incorporated over two billion people into a virtual polity, created a powerful psycho-political belief system (‘I share therefore I am’) and the effective ability to silence any person or media institution they deem unpalatable. It is a system of breathtaking scale that deserves comparison with the empires of the past. Romans like the poet Virgil glibly wrote of their ‘limitless’ Empire whilst believing that the edge of the world was the British Isles. Today Mark Zuckerberg has come closer than any other figure to realising the dreams of the Augustan age.

The question is not how this affects our democracy (badly), or the minds of our children (deleteriously), or what the moral character of the man is (unremarkable).

It is whether he can control the monster he’s summoned.

To understand the power of Facebook we might take a look at its effects on the media industry. In the early 2010s Zuckerberg made the decision to shift the News Feed from personal news like holiday photos to ‘real’ news like something published by the Washington Post. The product showed headlines along with author bylines, a feature as appealing to the vanity of journalists as Twitter’s blue tick. By the end of 2013 Facebook had doubled its share of traffic to news sites. With the rollout of 2015’s Instant Articles, Facebook gave publishers the ability to publish directly on the platform. This might seem esoteric to the layman but the consequences of this tinkering were enormous. As Nicholas Thompson and Fred Vogelstein of WIRED put it: ‘Facebook now effectively owned the news.’

The year of Instant Articles was the same year Facebook surpassed Google as the leader in referring readers to news sites. At some point in this period it became clear that the system publishers relied on to distribute what they wrote was changing what they wrote. The medium really was the message. Publication on Facebook meant instant feedback. Editors didn’t have to wait for a mailbag anymore. If the content was good, it was liked and it was shared. Old standards of fact-checking, objectivity and intelligence began a melancholy withdrawal into irrelevance.

Facebook’s News Feed made no distinction between reporting and opinion, long reads and listicles, fact and fiction. Mighty publishers were having their lunch eaten by charlatans like UniLad and BuzzFeed. Opinion bled in to news copy. Anger surged through the network. Publishers now operate on a new unwritten rule: write the lowest thing you can think of for the stupidest person you know. That dynamic — give the people what they want, even if its a video of a man eating a cactus — has inaugurated a festival of idiocy unprecedented in media history.

News didn’t become fake. News became stupid.

Journalists like Evan Osnos write from too high an altitude to really understand these pressures. He graduated magna cum laude from Harvard twenty years ago and in the time since picked up a Pulitzer Prize for Investigative Journalism in 2008 and a National Book Award for Non-Fiction in 2014. The New Yorker will have subscribers regardless of what Facebook’s algorithms do to their content. Osnos has never had to make a Playbuzz quiz about breeds of dog because ‘it shares better on Facebook’.

He ends his profile with the naive notion that Zuckerberg can somehow redeem Facebook: ‘He succeeded, long ago, in making Facebook great. The challenge before him now is to make it good.’

But how exactly do you make two billion people ‘good’ without manipulating them in ways that rob them of their agency and their privacy? What can be gathered about Zuckerberg’s personality suggests the outline of a man who sees himself as enlightened, as a holder of a greater truth, somebody who is above accountability.