China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is touted by Beijing as an attempt at multinational economic cooperation and development, comprising everything from foreign direct investment to the development of infrastructure. However, the purpose of the BRI is not economic or cultural but strategic, and is an effort to mask the expansion of Chinese power. In its strategic intent, the BRI should be considered an imperial project alongside the likes of the British East India Company (EIC) or the Dutch East Indian Company, Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC). With the BRI, China is exercising the ‘imperial excuse’, just as the EIC and VOC did centuries ago.

The ‘imperial excuse’ is imperial expansion under the guise of economic or cultural development — an alloyed good that is proof of altruistic intent. An imperial excuse legitimizes the imperial power’s insertion of influence into other states while at the same time attempts to divert suspicions of neo-imperialist control by advancing a legitimizing principle. This is done in order justify control to the local population and international community.

The British and the Dutch empires were the poster children of the strategic-cum-economic-cum-

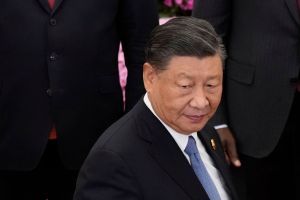

China’s vision for the BRI far exceeds the EIC or VOC. The BRI is the most expansive undertaking — physically, economically, and politically — of any single state in history. Rather than solely an economic venture, the BRI is a calculated strategic move, intended to lay the foundation for China’s dominance. Chinese President Xi Jinping has stated his intention for China to become the dominant state in international politics by the centenary of the Chinese Communist Revolution in 2049: ‘China champions the development of a community with a shared future for mankind, and has encouraged the evolution of the global governance system. With this we have seen a further rise in China’s international influence, ability to inspire, and power to shape; and China has made great new contributions to global peace and development.’

The BRI is a key part of how China will forge this ‘shared future for mankind’. According to the Chinese, the BRI will maintain the principles of harmony, inclusiveness, and cooperation with mutual benefits. The results will be a wealth of mutual benefits for the participants. That is a good imperial excuse as they come, and ranks, if not exceeds, what the creative minds of the EIC or VOC conceived.

Within the BRI, new institutions will ensure its success, and like its imperial antecedents, Beijing will brook no significant challenge to them. For example, in the fall of 2017 the International Chamber of Commerce’s International Court of Arbitration announced that it would establish a special commission for the sole purpose of resolving disputes brought about by the BRI. Responding with alacrity, in January of 2018, Beijing released its own plan to create its three international commercial courts, with the same sole purpose of handling BRI disputes. The courts are stationed in Beijing, Shenzhen, and Xi’an and will be under the full authority of the Supreme People’s Court (SPC). Each court has its own geographical jurisdiction but all will cover the same commercial jurisdiction. The Shenzhen court will manage cases involving the Maritime Silk Road Initiative and the Xi’an court will field cases coming from Silk Road Economic Belt.

The notion of judicial independence can be dismissed immediately. The BRI Courts are under the jurisdiction of the SPC, which is merely an extension of the Chinese Communist Party. Beijing simply rejects the authority of foreign judges or of permitting foreign legal representation. This is understandable from the PRC’s point of view as one of the goals of the BRI Courts is to force other sides to accept Chinese mediation and arbitration. China will coerce the BRI’s participants into allowing its courts to have jurisdiction over disputes arising from the Initiative. The consequence of this is to ensure the lack of a fair process and permit China to interfere in the domestic courts and politics of its participants. Despite its importance, fair judicial practice is not the greatest challenged posed to the BRI’s participants.

Although China has been careful to structure the BRI’s institutions to serve its interests, that is only a part of China’s objective. The BRI encompasses a holistic strategy to ensnare participants including investment, debt traps, and political interference. Underdeveloped African countries are particularly susceptible given their various forms of unstable governments and overall poor economies. China relieved $40 million of the debt Zimbabwe owed and while it is still in the hole for another $1 billion, the gesture led to Zimbabwe promising to use the Chinese yuan more in its foreign exchange reserves. In Kenya, the crown jewel thus far has been the rail line China developed from Nairobi to the port of Mombasa, which will be able to transport Chinese goods throughout the country more easily. Nigeria’s economy is dependent on Chinese investment, which totals an estimated $45 billion in past and present development projects. In return, Nigeria exports crude petroleum, petroleum gas, and rubber to China.

Despite these impressive successes, the road has not always been a smooth one. China has had to deal with its fair share of setbacks from states that are a little more cautious about Chinese investment and infrastructure development. Negotiations have been slow going in a number of prospective states from fear of the dependency China is clearly fostering and a general unwillingness to fall into a ‘debt trap’, not unlike the one Sri Lanka unfortunately found itself in as it developed the strategically located Hambantota port. China provided large loans for its construction, and the 99-year lease that is now being held by a Chinese firm is an example of how developing states like Sri Lanka may easily fall into the ‘debt trap’. Indebtedness consequently provides an avenue of Chinese influence and control.

As for political interference, there are significant and troubling cases. The 2017 coup d’état in Zimbabwe that overthrew former President Robert Mugabe occurred after China informed Mugabe that they would be withdraw investments until the country could provide economic stability. Mugabe’s successor, Emmerson Mnangagwa, received military training in Beijing and Nanjing, and was seen as most likely to stabilize the economy. In Australia, the Dastyari case was the tip of iceberg regarding Chinese interference. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor has justified Beijing’s growing influence and presence to ‘protect’ investments and infrastructure like the port at Gwadar, potentially a major naval base for China. There are myriad other occurrences of political interference, from Latin America to Polynesia.

The vocabulary of imperial excuses is just as diverse as the empires they initiate. The excuse is given in different languages, informed by diverse ideologies, civilizations, and economic systems, but their motivations remain the same. The lessons of the past imperial excuses find their echo in China’s initiative. China’s effort is only the latest in a long line of imperial projects masquerading as economic development, and should be considered an attempt at imperial expansion. The BRI may very well be the defining pivot of the century to come The imperial excuse of the BRI, like its antecedents, advances Chinese interests and masks China’s control. Greater transparency about what China is actually doing will permit the imperial excuse to be seen as the mask designed to conceal Chinese neo-imperialism.

Sarah-Madeleine Torres is a graduate student at the University of Texas San Antonio. Bradley A. Thayer is a professor at the University of Texas San Antonio and the co-author of How China Sees the World: Han-Centrism and the Balance of Power in International Politics.