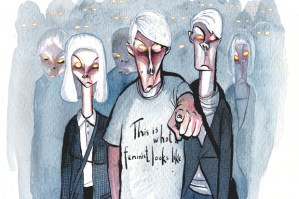

Universities are not the calmest of places just now, what with fights over free speech and the endless claims of harassment and intimidation. Add in the crippling debts from a college education, and many students might be wondering why they bothered at all.

But never mind the on-campus animosity and rivalries, a university education ultimately has a beneficial effect on those who go through it – and not just in a financial sense. It make us more trusting and optimistic about the intentions of other people. That is the clear conclusion of the American Enterprise Institute’s Survey on Community and Society, which I co-authored.

The survey asked graduates aged 24 and over three questions about interpersonal relations. The first was, ‘would you say that most people can be trusted, or that you can’t be too careful in dealing with people?’ Of the college graduates, 58 percent answered ‘yes’ compared with just 27 percent of those whose education finished at high school. The national average is 42 percent and there were minimal differences in the geographical distribution of answers – it was solely a college education which was associated with a high level of trust in other people.

The next question asked: ‘Would you say that most of the time people try to be helpful, or that they are mostly just looking out for themselves?’ Again, there was a big difference in attitudes, with 70 percent of college graduates agreeing with the statement compared with 49 percent of those who were educated only to high school level.

Finally, taking a darker turn, the survey asked if Americans think that most people would try to take advantage of them if they got a chance, or would they try to be fair? The educational difference emerged again, with 59 percent of non-graduates taking the pessimistic view, compared with only 32 percent of graduates.

It isn’t that graduates are as a whole more engaged with their communities. When asked about knowing their neighbors well or fairly well, slightly higher numbers of high school graduates turned out to know their neighbors compared with college graduates – 57 percent compared with 52 percent. Identical proportions of both groups – 54 percent – said they talk to their neighbors a few times a week or more. When asked about if they can make a difference in their local communities, levels of optimism are very close, with 61 percent of college graduates and 55 percent of high school graduates thinking that they can have a moderate or big impact on their communities.

The difference between graduates and non-graduates is only significant when it comes to trustworthiness. The question is what is it about a college education which makes people more open towards and trusting of others? There are a number of possibilities. Curricula in the liberal arts and humanities explicitly present questions about what makes for a good or just society. In spite of the high profile cases where free speech has been under attack, collegiate campuses remain sacred places for dissent, debate and diversity of viewpoints.

It is also possible that living in shared, contentious spaces such as dormitories helps to breed trust in others, along with the simple reality of having to interact with fellow students on a regular basis.

One thing, though, is for sure: higher levels of trust in others are of benefit to society. Decades’ worth of research has shown that strong levels of social capital are essential for civic health and this capital develops from the prevalence of trust in society.

The new survey data makes a strong case that the benefits of trust and openness which are imparted as part of earning a higher education degree linger well after college life has ended. Thus as scholars, civic leaders, and policy-makers think about how to heal so many divisions and build community, they would be well served to promote higher education as a building block for developing trust in others, and thus greater civility in society.

Samuel J. Abrams is professor of politics at Sarah Lawrence College and a visiting scholar at the American Enterprise Institute.