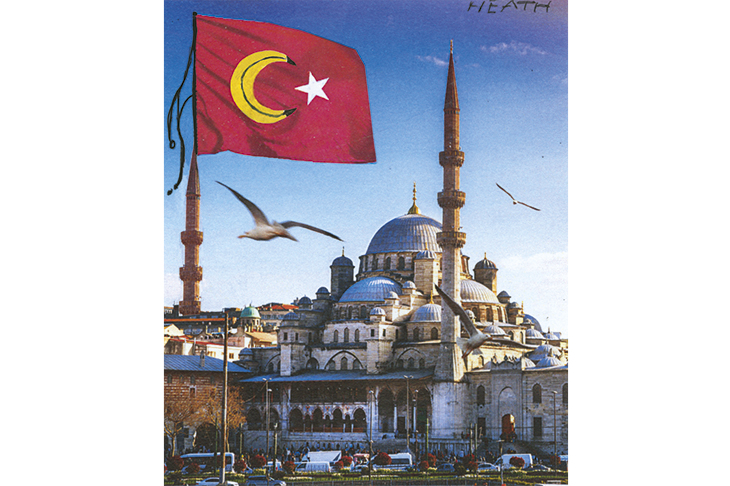

‘It’s official. Turkey is a banana republic!’ My friend Mustapha, a serial entrepreneur, sends me a flurry of doom-laden WhatsApp messages on hearing the news that Istanbul’s mayoral election is being re-run. One of them is a cartoon of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan standing in front of the national flag, crescent turned into a banana. In March, his ruling AKP lost Istanbul, the engine of what remains of the Turkish economy, together with Izmir and Ankara. It was a historic breakthrough for the opposition CHP and its victorious mayoral candidate Ekrem Imamoglu. But it was also a massive threat to Erdogan, a former mayor of Istanbul, who hasn’t lost an election since 1994. He alleged dirty tricks and leant on the election authority to order a re-run. Will the rest be history? Bulent Gultekin, a former Central Bank governor, tweets of a ‘coup’ against the will of the people: ‘The AKP has brought my fine country to the brink of political and economic collapse.’ Others reckon Turkey is drifting towards dictatorship. That evening I dine with Turkish friends on the Bosphorus. Ferries ply the waters, greedy gulls hover overhead and simit sellers do a brisk business with waterborne commuters. We digest the momentous news over lamb chops and a bottle of raki. ‘Remember this day,’ says Ali, a poet. ‘It’s the day Turkish democracy died.’

The economy is tanking, the lira is plummeting and unemployment is at a ten-year high of 15 percent. So what does the president do? The answer is visible in the skyline above Uskudar on the Asian side. If any city could be said to have enough mosques it is surely Istanbul, but Erdogan has decided it needs another. While I am in town he inaugurates the Camlica Mosque, Turkey’s largest, with a capacity of 63,000. Estimated cost $100 million. Joining him at its B-list opening are the presidents of Albania, Guinea and Senegal. All very well as a distraction, but not much good for the beleaguered Turkish economy. Experts reckon Erdogan is going to have to swallow his pride soon and come to the IMF with his begging bowl.

Mustapha tells me how Erdogan’s network of family and cronies, taking their lead from the president’s son Bilal, routinely plunder businesses, including his own. ‘I built up a really nice business over 10 years and then they came in like gangsters and took it all away,’ he says. ‘It can’t be reported because journalists get charged with terrorism and put in prison. What’s disgusting is that they do this while telling us to be good Muslims.’ For years the AKP in Istanbul has been funneling money to conservative charities connected to the government to shore up its base, treating public finances like a private piggy bank. Around $100 million has gone like this in the past year. This is why Erdogan can’t afford to lose Istanbul.

Historians love parallels. For a few days Istanbul is crawling with British travelers, travel writers, publishers and art experts, and I’m reminded of one of the great travel novels, in which ‘half the litterateurs of England were off writing their Turkey books’. Published in 1956, Rose Macaulay’s The Towers of Trebizond opens with one of the most memorable lines in English literature: ‘“Take my camel, dear,” said my aunt Dot, as she climbed down from this animal on her return from High Mass.’ At one point, Reverend the Honorable Father Hugh Chantry-Pigg, introduced as ‘an ancient bigot’, cautions Dorothea ffoulkes-Corbett against traveling to Russia, because its government persecutes Christians. ‘If one started not condoning governments, one would have to give up travel altogether, and even remaining in Britain would be pretty difficult,’ the irrepressible Aunt Dot replies.

These days it’s the Ankara regime which is banning people it doesn’t like from traveling to Turkey. The British-Turkish writer Alev Scott, author of the excellent Ottoman Odyssey, recently joined the lengthening list of personae non gratae. Tens of thousands of innocent Turks have been rounded up and imprisoned in one of the most far-reaching purges in living memory. The army, media, judiciary, teachers, police and civil service have all been completely emasculated, inconvenient election results overturned. This is how dictatorships begin. ‘It makes me proud how fiercely determined my friends are to vote for Imamoglu a second time,’ says Scott. ‘But I’d be less surprised if he ended up in jail than if he ends up mayor.’ For those who argue political Islam and democracy are incompatible, Erdogan is Exhibit A.

The heavens open, thunder and lightning transfix the city, and streets become raging rivers. In May 1453, with the Ottoman army of Sultan Mehmet II at the gates of Constantinople, the city was hit by another apocalyptic storm: hail, driving rain and torrents of floodwater so severe that a procession invoking the protection of the Virgin Mary had to be abandoned. A few days later, the ancient Christian capital finally fell after 800 years resisting Muslim armies. This storm seems to presage a different disaster. Will it be Turkey’s descent into outright dictatorship? Hold tight for Istanbul elections 2.0 on June 23.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.