With Central and Eastern European countries still gripped by COVID-19, the EU’s slow vaccine rollout has offered little solace in the region. The light at the end of the tunnel seems far away, leading many to wonder whether the answer to vaccine shortages lies not in Brussels, but to the East. Interest in Russian and Chinese vaccines is certainly fast becoming a diplomatic issue for the region.

Czech prime minister Andrej Babiš recently caused a stir with two international visits. The first was to his Visegrád Four ally Hungary, the second to non-EU Serbia, far and away mainland Europe’s vaccine leader:

Babiš suggested both trips were made with the intention of working out what these countries’ vaccine programs got right.

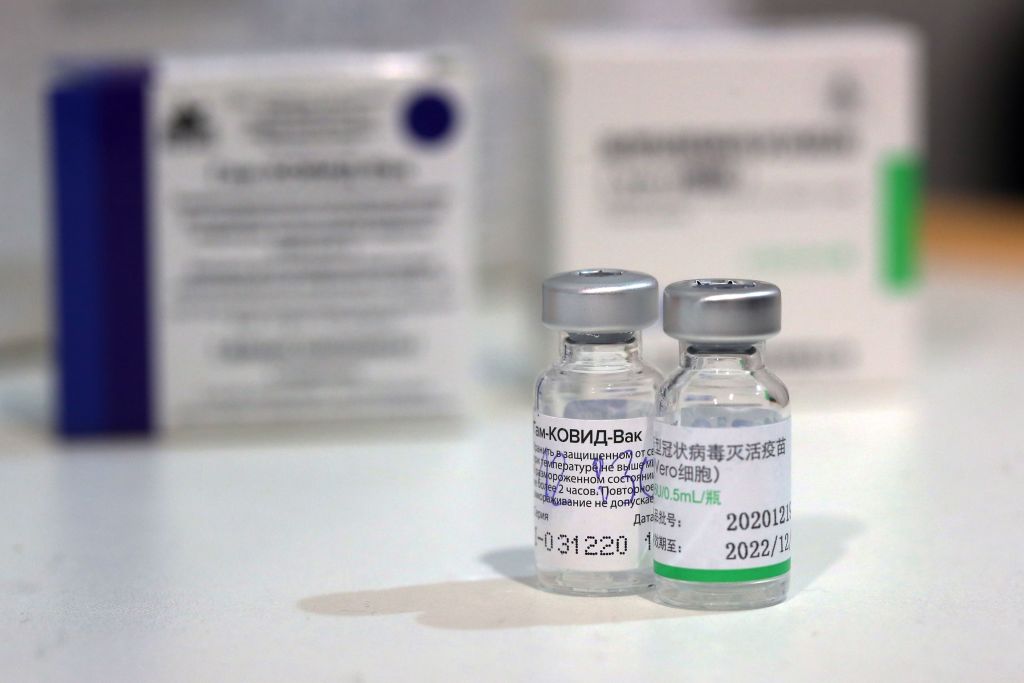

A defining characteristic is their readiness to use vaccines developed by Russia and China. Hungary recently became the first EU country to start using the Russian Sputnik V vaccine, and will soon begin administering the Chinese Sinopharm jab, having taken the approval of both medicines into its own hands. Serbia’s rapid rollout has been achieved thanks in large part to its use of the Russian and Chinese vaccines.

When Babiš departed for Hungary and Serbia, it seemed a distinct possibility that the Czech Republic would also approve the Russian and Chinese jabs. The Czech Republic’s former health minister and key epidemiologist Roman Prymula openly discussed the possibility of departing from the centralized EU approval system, citing the risks of pan-European delays. Babiš as well did not deny the possibility that Sputnik vaccines could appear in the Czech Republic without EMA approval.

Suddenly, though, the mood has changed. In recent days Prymula, Babiš and health minister Jan Blatný have stated that the data from Hungary and Serbia is insufficient to justify the independent approval and usage of Sputnik V, claiming no vaccine will be used in the Czech Republic without EMA approval.

With Sputnik V already ordered in a number of non-EU Eastern European countries, this volte-face is leading some to wonder whether ‘vaccine diplomacy’ is playing a role. Disputes about the Russian vaccine’s EMA application status have emerged in recent days, making it seem unlikely that Sputnik V will be approved by the EU anytime soon. In a recent meeting of V4 prime ministers, Hungarian leader Viktor Orbán pressed his counterparts to set aside their geopolitical concerns and use the Russian jab — but in a region which is no stranger to conflicts with Brussels, the approval of Sputnik could provoke a crisis in the EU.

Sputnik V isn’t the only vaccine stoking diplomatic tensions. In the recent annual 17+1 summit between ex-Soviet-bloc countries and China, President Xi Jinping emphasized the availability of Chinese vaccines to Eastern European nations, describing them as ‘cheap and easy to produce’.

China may see Central and Eastern Europe as a promising market for vaccine sales, but relations between Beijing and ex-Soviet-bloc countries are complex. Some heads of state stayed away from the 17+1 summit due to unkept promises from China on investment and trade. There are also suspicions that the format is intended to sow divisions within the EU.

Public attitudes towards Chinese vaccines are also skeptical: according to one recent study, only 2 percent of Czechs would feel absolutely confident taking a Chinese jab.

Nevertheless, the Hungarian and Serbian use of the Sinopharm vaccine has led to speculation that it may soon appear in other countries in the region. Sinopharm is officially applying for EMA approval, and Central and Eastern European pressure may lead to EU regulatory bodies expediting the process.

Following the EU’s mishandling of the first phase of vaccine procurement and rollout, it is significant that Eastern powers like China and Russia are attempting to gain the confidence of Central and Eastern Europe. The region’s faith in the current vaccine program, using jabs from Europe, the USA and Great Britain, seems to have been shaken not only by shortages, but also by doubts over the efficacy of the AstraZeneca vaccine. Scare stories have led to elderly Czech citizens canceling vaccination appointments when told they would receive the Oxford jab. And the problem of vaccine skepticism isn’t limited to this vaccine alone: only 15 percent of Czechs would take a US-made vaccine without hesitation.

A narrative of western failure plays into the hands of political forces favoring closer ties with Eastern powers. Czech President Miloš Zeman has long been accused of favoring relations with the East over those with the EU and Nato, and has already expressed his support for the use of Sputnik V in the Czech Republic. In response to the Chinese vaccine sales pitch at the 17+1 summit, Zeman called for a new ‘Silk Road’ linking China with Eastern Europe. By linking vaccine procurement to closer economic relations, he put ‘vaccine diplomacy’ front and center.

Nations like the Czech Republic may be siding with the EU’s regulatory bodies when it comes to Sputnik V, but this allegiance seems fragile. The EU’s vaccine program has given rise to doubts about the bloc’s ability to protect its member states. Tempting offers from the East mean the pressure is now on for the EU to prove its worth to its Central and Eastern European members.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.