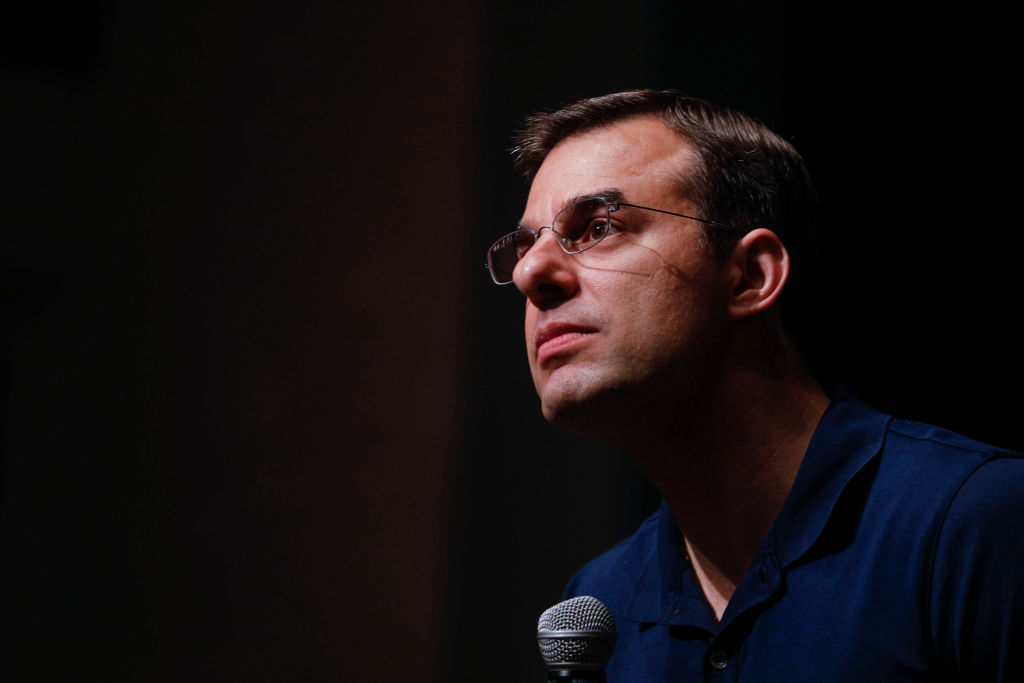

Every Democrat’s favorite ex-Republican has just announced he’s going to seek the Libertarian Party nomination for president. If he gets it, Justin Amash will be the third ex-Republican in a row to be the LP’s standard bearer, tracing the footsteps of former Georgia Rep. Bob Barr (2008) and former New Mexico Gov. Gary Johnson (2012 and 2016). Neither of those two had an appreciable impact on the Obama-McCain, Obama-Romney, or Clinton-Trump contests, and the odds are not good that Amash will be any more significant.

So why is he running? The immediate explanation is probably that he concluded he couldn’t win his race for re-election to Congress. He’s younger than Barr or Johnson, and if he wants a future as a pundit, a third-party presidential bid serves him better than a humiliating defeat in his House race. Amash made headlines last year by quitting the GOP and throwing his support behind the Democrats’ impeachment effort. He won strange new respect from liberals and neoconservatives — not exactly the fanbase a principled libertarian craves, you might think. But since his moment of NeverTrump glory, he’s been a nonentity. A presidential bid, however futile, will raise his profile. It guarantees him a few more minutes of fame, and because he can be trusted to bash Trump more than Biden, the pro-Biden media (‘Tara who?’) will give him a megaphone. A small one, but that’s as good as he can get, so he’ll take it.

I’ve related before my impression from the first time I heard Amash speak. It was shortly after his first election in 2010, and he addressed a gathering sponsored by Young Americans for Liberty in conjunction with CPAC. YAL was founded by the youth coordinator of the 2008 Ron Paul campaign, and the Paul movement was instrumental in creating the conditions for the Tea Party and the election of libertarian-leaning Republicans such as Amash in the 2010 midterms. But in his remarks to YAL, Amash made a point of distancing himself from Ron Paul and his branch of the libertarian tradition. This seemed preening and ungrateful, but at the time I chalked it up to a politician’s simple desire to be his own man. He was inexperienced, and if he struck the wrong note, it probably wasn’t deliberate.

But it turned out that Amash’s self-conscious separation from Ron Paul and the Tea Party was the beginning of a pattern. Again and again, Amash has made a point of pretending to be better than everybody else, especially those who work alongside him. He was too good for the Ron Paul movement, too good for the Tea Party, and ultimately too good for the Republican party and the House Freedom Caucus. A humbler man might have asked himself why every other Republican — including equally or even more liberty-minded ones, such as Kentucky’s Rep. Thomas Massie — was opposed to impeachment. Your friends and allies might be wrong, but they’re presumably your friends and allies in the first place because you think they’re generally on the right side. And if you think they’re wrong in a particular instance, friendship and loyalty would argue that you should try all the harder to convince them to change, and not simply break off the relationship. But Amash isn’t about persuasion, he’s about preening his own feathers.

In this, as in so many things, he’s the opposite of Ron Paul. Dr Paul also left the Republican party to run for the Libertarian nomination, back in 1988. He did not do it in a snit, however, or in a self-dramatizing way. And when the Libertarian party proved to be a lousy vehicle for advancing liberty, Dr Paul returned to Congress as a Republican again. His 2008 and 2012 runs for the Republican presidential nomination were far more successful than his 1988 LP bid in building a liberty movement — in getting others elected to office, including Amash, Massie, and Paul’s son Rand; in awakening the interest of a new generation in constitutionalism and Austrian economics; in establishing new institutions such as Young Americans for Liberty; and in raising for the whole country important questions about war and the Federal Reserve. Paul was never running just to show that he was right, he was running to plant the right ideas in institutional soil, where they had a chance of success. That meant running within the Republican party, for all its flaws, and it meant focusing more on ideas themselves than on the question of who was right or wrong.

Justin Amash is not known for ideas — in his time in Congress, he hasn’t made foreign policy or monetary policy or anything else as conspicuous a theme as his own rebellious attitude. Sometimes the rebellions were justified, as when he voted against John Boehner as speaker of the House of Representatives. (Though interestingly, only Massie dared vote against Paul Ryan — Amash supported him.) But what has marked Amash’s politics more than any particular issue is his claim to personal moral superiority, including over his own closest allies. He truly is the anti-Ron Paul: instead of devoting himself to liberty and the Constitution, he uses the Constitution and liberty as pretexts for his own vanity. Why, criticize me and you are really criticizing the rule of law itself — harrumph!

The Libertarian party may indeed be the appropriate home for someone who places his own conceit above anything resembling political effectiveness. Third parties are mostly harmless, but that’s the problem: if you have a limited number of supporters and limited financial resources, and you really want to make your ideas matter, you will get more mileage for every voter and every dollar in a smaller electorate than in a bigger one. In other words, put your money and manpower into a Republican or Democratic primary, where the electorate is much smaller than in a general election, and you have a better chance of scaring the establishment into taking up your issues even if you don’t win. This strategy has proved itself time and again in both major parties’ primaries, which is why the establishment is eager to bring back the so-called ‘smoke-filled room’ where activists and the public don’t get a vote. (And isn’t it curious how elite pundits, for all their talk about democracy, are shameless about pining for this exquisitely anti-democratic form of politics?)

The general election is the battlefield in which a small number of votes can be least effective. So what is the Libertarian party all about? It hasn’t been about building any consistent, nation-changing force for liberty — the fact that it doesn’t even have a leadership cadre of its own, but every four years now turns to a former Republican as its presidential standard-bearer, is revealing. The Libertarian party doesn’t bring about any great new passion for liberty among people with talent. It’s not really a political party because it does virtually nothing that affects politics. But it’s also not a force for ideas — whatever success libertarian ideas have found in the last half-century hasn’t come about because of the LP.

***

Get three months’ free access to The Spectator USA website —

then just $3.99/month. Subscribe here

***

The Libertarian party is instead an example of something that libertarians otherwise find suspicious, an institution that exists only for the sake of continuing its own existence: a bureaucracy or a sinecure for its own officers. This is why whenever the opportunity is available, the LP nominates some former Republican officeholder: the party needs the attention more than it institutionally needs to promote liberty. The business can go on with longtime drug-warrior Bob Barr as the party’s nominee; it can’t go on with a series of no-name ideologically pure libertarians on the ticket.

The Libertarian party is not a political party, it’s a publicity racket. Justin Amash is no longer a politician. He’s an advertisement. Amash is his own cause, a movement for one man, who identifies the Constitution, the rule of law, and the cause of liberty with himself alone. The Libertarian party craves publicity enough to make room for him, but don’t count on Amash to pay back the Libertarian party in years to come.