Mark Sanford might not eat brains, but he is the closest thing in American politics to the living dead, an authentic Zombie Republican. His career died a decade ago when he was governor of South Carolina and absented himself from office for a few days to go off hiking the Appalachian Trail – or rather boffing the Argentinian mistress.

He was censured, nearly impeached, but clung to office anyway until his term expired in 2011. And then, two years later, he shambled back to a familiar haunt, the US House of Representatives.

Sanford began his brief national career as a Class of ’94 House Republican insurgent. And there he was again, nearly a decade later, after winning a 2013 special election. He was like an old college dropout going back for his degree after getting divorced. He brought with him the nostalgia of ’94, warmed up to Tea Party temperature. This refurbished libertarian-ish Republicanism met its end in the 2018 South Carolina primary. Sanford lost to a pro-Trump challenger who bashed him for his criticisms of the president.

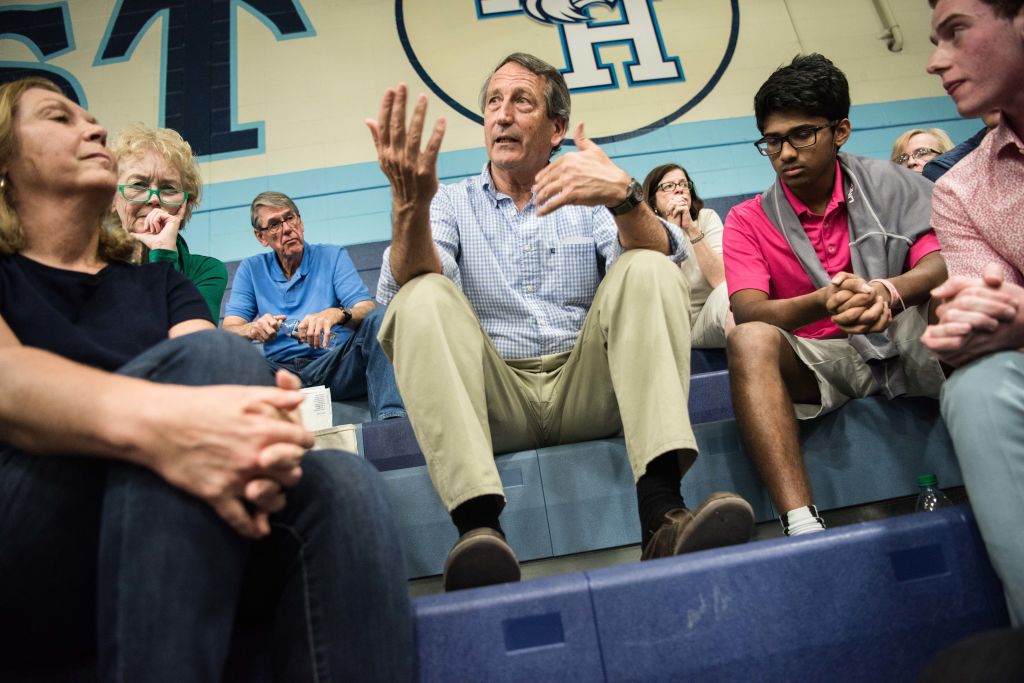

Now the disgraced governor and cashiered congressman is back again to run against Trump himself for the 2020 Republican presidential nomination – though Sanford will be lucky to finish third in a race that also includes 2016 Libertarian party VP nominee William Weld (long ago a liberal Republican governor of Massachusetts), and former one-term congressman Joe Walsh (famous for insisting that Obama was a Muslim, though before that he, like Weld, was on the Republican left and favored abortion rights). The anti-Trump field is so bizarre and pathetic that it only stands to make the president look better by comparison: truly this is 12-dimensional chess.

Although the most prominent NeverTrump personalities are neoconservatives – Bill Kristol, Max Boot, etc. – Trump’s challengers from within the GOP come mostly from the libertarian wing of the party. As of 2015, Mark Sanford and Rep. Justin Amash from Michigan were roughly half of the GOP’s plausibly libertarian congressional representation. Libertarians have a catflap relationship with the GOP: they can’t decide whether they’re in or out. Ron Paul was a Republican congressman, then left to become the 1988 Libertarian party presidential nominee, then came back to be a Republican congressman (and two-time presidential candidate) again. Amash has left the Republican party and might yet seek next year’s Libertarian nomination. Weld, who was a Libertarian last time around, is now a Republican once again. Libertarian pundits and academics protest loudly that they aren’t Republicans or conservatives, but the Libertarian party has nominated ex-Republicans as its presidential standard bearers in each of the last three elections (Bob Barr in 2008, Gary Johnson in 2012 and 2016).

Of them all, only Ron Paul has had any impact on the GOP or national politics. Not coincidentally, Paul is also the only one who ran most strongly on a non-interventionist foreign policy (a theme Trump took up in 2016) and criticism of the banking system. Paul also made a point in his Republican presidential campaigns of opposing efforts to create a North American Union of sorts: a Nafta superhighway or an ‘Amero’ currency were never close to becoming realities, but Paul clearly understood that sovereignty was deeply important to American voters, particularly Republicans, and the direction of elite thinking was away from self-government and toward transnational institutions.

Those aren’t themes that Sanford appears inspired to pick up: appearing on Fox News Sunday, he defined his campaign as an effort to get people talking about spending, deficits, and the national debt. The last hit $22 trillion this year, and any deficit hawk has cause for complaint with President Trump. Trouble is, deficit hawks are extinct in the wild. Although virtually nobody likes debt in the abstract, in politics deficits and debt are the result of two things that Republicans and Democrats place a far greater value on: tax cuts and government spending. Republicans are happy to hold down spending when a Democrat is in the White House, but given a choice between becoming really unpopular by cutting entitlements and services that voters want in order to reduce the debt – an act that would cost whatever political capital might otherwise be spent on tax cuts – or accepting higher deficits in order to make cutting taxes easier, Republicans reliably go for the latter. They justify this by telling themselves that lower taxes will stimulate enough growth to make the deficits bearable. Democrats, of course, don’t want to cut popular services or entitlements, they’d like to spend even more on them, but raising taxes in order to do so would court a voter backlash. So Democrats too prefer deficit spending to pay-as-you-go. And they also believe that prosperity will result and limit the hazards posed by the debt.

Political logic is hard against Sanford’s effort, but the realities of mega-finance pose an even bigger problem for him. If the ballooning deficits were affecting America’s creditworthiness, you would expect interest rates to rise. But they aren’t. American debt remains very attractive to foreign buyers because it’s considered very safe and still offers nominally positive returns – unlike the negative interest rates to be had from every other advanced nation’s debt today.

The depth of America’s debt pool has also become a stabilizing factor in its own right, at least as many modern investors see it: where else can one park many billions or trillions of dollars over the long term without serious uncertainty? America’s 30-year financial horizon doesn’t have to be blindingly bright, it only has to be brighter than the 30-year horizons of Europe or China. Those financial prospects are, of course, heavily influenced by political prospects. The world is more confident that America will still be America in 30 years’ time than Europe or China will look anything like what they do today. China will either be vastly more powerful or in utter turmoil. Europe won’t be vastly more powerful and has a dozen different roads to turmoil. America is comparatively a better bet.

But that just means a bad game can go on a lot longer. Sooner or later, the debt really will weigh down future growth to a dangerous degree, and interest rates will rise. America could even go bankrupt. Yet here libertarians and libertarian-ish politicians like Mark Sanford run into a contradiction. To face a long-term challenge by making painful choices and changes now requires great national solidarity: the people must have a shared spirit of sacrifice and great trust in the leaders who are asking them to give up something now for the sake of future generations. This is exactly what libertarian individualism cannot deliver – it’s an ideology that depreciates citizenship and preaches suspicion of political leaders. Willy-nilly, that’s going to apply to libertarian political leaders as well. It’s also an ideology of indifference, if not hostility, toward nationhood and one’s own posterity. If America goes bankrupt, it doesn’t matter, because you can always move the firm to Ireland or Hong Kong or Mogadishu or Kabul. You don’t have to worry about posterity if you don’t have any children, or any pre-existing relationship with the strangers who will inhabit your country after you’re gone. Live for today: hike the Appalachian Trail.

What Mark Sanford cares most about in politics is an issue that only matters within the framework of a nation with a sense of solidarity and continuity among its members. Libertarians who want to take on deficits and spending have to begin by committing themselves to their country. Sanford would do a great service, if he achieved nothing else, by teaching this lesson to his supporters and sympathizers: libertarianism needs nationalism, too.